Death of a Regulator

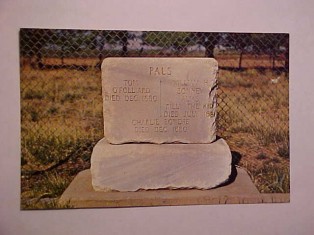

William H. Bonney, better known as Billy the Kid, drifted through New Mexico in the mid-1870s, defying the law and becoming famous in the process. By the time he turned age sixteen, he had killed one man and been jailed twice. Desperate circumstances and a misplaced sense of justice was what spurred Billy on toward his life of crime. Born in New York on November 23, 1859, Billy was the younger of two boys. His father died in 1864, leaving Billy’s mom alone to look after the children. In 1873 she moved her sons to Indiana, where she met and married a man named William Antrim. Antrim took his new wife and her family to Silver City, New Mexico. The four no sooner arrived than William Antrim abandoned his new family to prospect. Billy’s mother managed a hotel to support her boys, and Billy worked with her. In 1874 she was diagnosed with tuberculosis and died shortly thereafter. Billy was fourteen years old. Not long after his mother’s death, Billy had his first run-in with the law. The clothes he stole from a Chinese launderer’s business were meant to be a teenage prank, but the act was perceived as malicious theft to the local authorities. Wanting to teach Billy a lesson, the sheriff decided to lock him up. After spending two days in jail, Billy escaped and made his way to Arizona. In 1877 Billy was hired on at a sawmill at the Camp Grant Army Post. The blacksmith who worked at the military post was a bully of sorts and took an instant dislike to Billy. He frequently made fun of him, taunting him until the teenager snapped and called the blacksmith a name. That was the cue he was waiting for and he attacked Billy, and Billy shot him. He was arrested for the killing the following day and subsequently escaped. Billy roamed about New Mexico’s Pecos Valley in Lincoln County, working odd jobs at various ranches and farms. Wealthy English cattle barren John Tunstall eventually offered the restless young man full-time employment to watch his livestock. Billy took the job with great zeal-Tunstall was kind to him, and Billy appreciated his integrity. Not everyone felt that way about Tunstall. A pair of rival merchants and livestock owners who were resentful of his riches were determined to destroy the man and his holdings. The heated battle, which erupted between the established business owners and ranchers who had a monopoly on beef contracts for the army, and entrepreneurs such as John Tunstall, was referred to as the Lincoln County War. As an employee of John Tunstall’s, William Bonney found himself in the middle of the feud. It became a personal battle for him when the disgruntled ranchers had Tunstall gunned down. Billy first joined in with law enforcement to help bring the murderers in legally, but he ended up being jailed for interfering with the sheriff and his deputies. After his release Billy decided to take matters into his own hands and joined a posse bent on hunting down the killers. When the murderers were located, Billy and the other members the vendetta riders, known as the Regulators, shot them dead. The Lincoln County War ended in a fiery blaze on July 19, 1878, and a number of men were killed. Billy kept the Regulators together, and the boys ventured into cattle rustling. More people were killed along the way and Billy the Kid, as he was now called, was a wanted man. So Billy negotiated a deal with the governor of the state. If Billy turned himself in to the proper authorities and gave them information about those who participated in the Lincoln County War, he could go free. When the deal was agreed upon, Billy laid down his weapons and submitted to the arrest. After Billy was incarcerated, the district attorney went against the governor’s arrangement with the Kid and promised to see him hanged. An enraged Billy the Kid escaped from jail and went on the run-managing to elude the authorities for two years. In 1880 Pat Garrett was sworn in as the new Lincoln County sheriff and assigned the duty of apprehending Billy the Kid. He had a reputation as a determined lawman and expert tracker, and he was persistent in his efforts to bring the Kid to justice. After laying several traps for Bonney, Garrett arrested him in April 1881. Billy the Kid was tried, found guilty, and sentenced to be hanged, but he escaped before making it to the gallows. Garrett again pursued the young fugitive and caught up with him after two months. Billy the Kid was hiding at a ranch near Fort Sumner, New Mexico. Under the cover of darkness, Garrett waited for Billy to appear and then shot him on sight. “All this occurred in a moment,” Garrett later told journalists. “Quickly as possible I drew my revolver and fired, threw my body aside and fired again…the Kid fell dead. He never spoke,” Garrett explained. “A struggle or two, a little strangling sound as he gasped for breath, and the Kid was with his many victims.” Garrett went on to describe the scene of the outlaw’s demise as a sad occasion for those closest to him. “Within a very short time after shooting, quite a number of native people had gathered around, some of them bewailing the death of a friend, while several women pleaded for permission to take charge of the body, which we allowed them to do. They carried it across the yard to a carpenter’s shop, where it was laid out on a workbench, the women placing lighted candles around it according to their ideas of properly conducting a ‘wake for the dead.’” On July 16, 1881, the day after Billy the Kid was shot, he was buried at the Old Fort Sumner Cemetery (a military cemetery) in DeBaca County, New Mexico. He was placed in the same grave as his friends Tom O’Folliard and Charles Bowdre. Both boys had been shot and killed by Garrett and his men in December 1880. The single tombstone over the plot lists the three desperados’ names and the word PALS. You’ll find more stories about the deaths and burials of the Old West’s most nefarious outlaws, notorious women, and celebrated lawmen in the book Tales Behind the Tombstones.