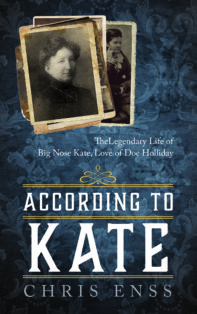

Enter now to win a copy of the book According to Kate:

The Legendary Life of Big Nose Kate Elder, Doc Holliday’s Love

Along with a Kindle Paperwhite.

In the winter of 1872, Wendell Phillips, orator, attorney, and the soul of John Brown marching on, delivered a lecture to a large audience of concerned citizens in St. Louis, Missouri, about the social cancer that plagued society. He pounded the lectern he stood behind while addressing the crowd and advised them to take a stand against intemperance, crime, and prostitution. Phillips was appalled that city officials had legalized the profession and were issuing licenses to the owners of houses of ill repute and the bawdy women who worked there. Almond Street, a popular thoroughfare five blocks west of the riverfront, was the location of many of those houses. It was Phillips’ hope that after the residents of St. Louis heard his fiery speech they would demand the businesses be closed.

“The root of this vice is poverty,” Phillips proclaimed. “It is because the poverty of a certain class makes them the victims of the wealth and leisure of another. Give one hundred men anywhere an honest career and a chance at the grand opportunities of life, and ninety out of the hundred will distain to steal. Give one hundred women a fair chance at the grand opportunities that their brothers have and ninety out of the hundred will disdain to barter virtue for gold.” Mary Katherine Horony, now known as Kate Fisher, was one of those near Almond Street who bartered virtue for gold. Poverty had played a part in her decision to become a sporting woman, but she was satisfied the work possessed possibilities beyond money. Kate was a business woman — nothing more, nothing less.

St. Louis had given Kate and other sporting women the opportunity to do their job without fear that law enforcement would interfere. The “social evil ordinance” the city had passed in March 1870 not only required prostitutes to obtain licenses but also mandated business women to submit to medical exams testing for venereal diseases. Civic leaders hoped the controversial ordinance would ultimately reduce the spread of disease. Many opposed the idea, arguing that it “encouraged the very vice which all good men and women destined to see suppressed.” Many soiled doves never bothered to register. Kate was one of those women.

The spirited, Hungarian woman must have been able to take care of herself against intoxicated and belligerent clients. Prostitutes sometimes found themselves in the company of men who resented their services. They hated themselves for hiring sporting women and blamed those women for the ills of society. A listing of arrests in daily, St. Louis papers showed how many acts of violence against prostitutes occurred nightly. The August 29, 1872, edition of The Macon Republican contained information about the circumstances surrounding the beating deaths of more than ten, bawdy ladies in the area of Popular Street in St. Louis.

“Eleven wretched criminals victimized prostitutes overnight,” The Macon Republican article began. “A man named Burklin shot a sinful woman when crazed with drink and jealousy; another killed a woman with a grubbing hoe; a third tossed the prostitute out a third story window; three were stabbed to death; the seventh prostitute was beaten to death with a soda water bottle; two were strangled; two were hanged by the neck with a rope.”

To learn more about Kate read

According to Kate: The Legendary Life of Big Nose Kate Elder,

Doc Holliday’s Love