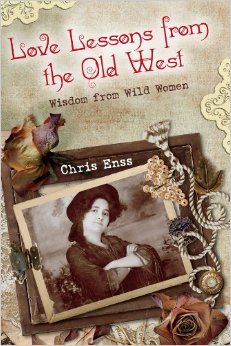

Zoe Agnes Stratton

Love and the Lawman

Lawman Bill Tilghman opened his eyes to flickering candle-light. He was in a bunk, covered with blankets. His shoulder was aching and stiff with bandages. He was thirstier than he could ever remember. He turned his head slowly and the movement brought a woman’s figure out of the shadows. “How are you feeling?” said a quiet voice. “Thirsty,” Bill mumbled. A tin cup of water was held to his lips. Bill drained it and sighed with satisfaction. In the thin candle-light Bill looked gaunt, his face hawkish, and his hair was grizzled in spots to silver. “You’ve lost a lot of blood,” the woman said, sitting down beside him. “You need to stay put.” Bill closed his eyes, and sleep took him.1

Golden sunlight was slanting through a window when Bill awoke. His head was clear, his eyes no longer fuzzy. He was hungry as a wolf. There beside him was his wife, Zoe, the woman he had seen by his side the night before. Bill was a United States marshal in the Oklahoma territory. An encounter with a pair of desperate criminals who were trying to smuggle whiskey onto a Native American reservation in 1903 had left him seriously injured. Zoe had tended to his wounds and stayed with him until he was able to get back on his feet.2

The pair hadn’t been married long, but Zoe knew her husband’s job as a lawman was dangerous and was prepared to do all she could to support him. William Matthew Tilghman became a law enforcement officer in 1877. He was, according to his friend and one time fellow lawman Bat Masterson, “the best of all of us.” Bat was referring to all the lawmen in the west. Zoe didn’t disagree.3

Born on November 15, 1880, in Kansas, Zoe Agnes Stratton was twenty-three when she married Bill. He was more than twenty years older than she, but he suited the school teacher turned author perfectly. “He was a Christian gentleman,” Zoe told reporters at the Ada Evening News on April 16, 1960. “He was quiet, kindly, greatly respected, and loved.”4

Born on the fourth of July 1854 to an army soldier turned farmer and a young homemaker, Bill spent his early childhood in the heart of Sioux Indian territory in Minnesota. Grazed by an arrow when he was a baby, he was raised to respect Native Americans and protect his family from tribes that felt they had been unfairly treated by the government. Bill was one of six children. His mother insisted he had been “born to a life of danger.”5

In 1859 his family moved to a homestead near Atkinson, Kansas. While Bill’s father and oldest brother were off fighting in the Civil War, he worked the farm and hunted game. One of the most significant events in his life occurred when he was twelve years old while returning home from a blackberry hunt. His hero, Marshal Bill Hickok (Wild Bill), rode up beside him and asked if he had seen a man ride through with a team of mules and a wagon.6

The wagon and mules had been stolen in Abilene, and the marshal had pursued the culprit across four hundred miles. Bill told Hickok that the thief had passed him on the road that led to Atkinson. The marshal caught the criminal before he left the area and escorted him back to the scene of the crime. Bill was so taken by Hickok’s passion for upholding the law he decided to follow in his footsteps and become a scout and lawman.7

Bill Tilghman set out on his own in 1871 and became a buffalo hunter. Using the Sharps rifle his father had given him, the eighteen year old learned the trade quickly and was an exceptional shot. He secured a contract with the railroad’s owners to provide workers laying track to Fort Dodge, Kansas, and the subsequent town that grew close to it, Dodge City, with buffalo meat.

From September 1, 1871, to April 1, 1872, Bill killed and delivered three thousand buffalo. He set an all-time record, surpassing the previous one made by Wild Bill Hickok. Bill Tilghman’s success as a buffalo hunter was due in part to his relationship with the Plains Indians. He never invaded their hunting grounds and treated them with dignity and reverence not commonly displayed by white men.8

Bill’s extensive knowledge of the territory prompted cattle barons like Matt Childers to hire him to round up his livestock roaming about the area and then drive them to the market at Dodge. He was exceptional at the job, but his true ambition was to become a law enforcement officer. He was a natural at settling disputes between friends and competitors engaged in heated arguments, a necessity for any policeman. Army colonels and other high-ranking military leaders wanting to help settle differences between themselves and angry Native Americans sought out Bill. Although he would not wage war with the Indians against the United States, he did understand their bitter feeling toward the white men. In hopes of driving the Cheyenne, Crow, and Blackfoot out of the country, the government ordered that their main source of food be slaughtered. The mighty buffalo was hunted to near extinction.

With the buffalo gone, Bill was forced to find other employment. From 1873 to 1878, he worked as a merchant, contractor, land speculator, horse racer, cavalry scout, and livery stable and saloon owner. He ran the Crystal Palace with his business partner, Henry Garris.9

The Palace was located on the south side of Dodge City, and refinements to the tavern made the news on July 21, 1877. According to the Dodge City Times, “Garris and Tilghman’s Crystal Palace is receiving a new front and an awning, which will tend to create a new attraction towards [sic] the never ceasing fountains of refreshments flowing within.” Bill also owned and operated a ranch thirteen miles outside of Dodge, one that he would never relinquish.10

As a proprietor of the Crystal Palace, some of the customers he befriended had questionable, and sometimes criminal, backgrounds. It was guilt by association that led to his arrest on suspicion of being one of the notorious Kinsley train robbers. On February 9, 1878, the Dodge City Times reported that “William Tilghman, a citizen of Dodge City, was arrested on the same serious charge of attempt to rob the train. He stated that he was ready for trial, but the State asked for 10 days delay to procure witnesses, which was granted. Tilghman gave bail. It is generally believed that William Tilghman had no hand in the attempted robbery.” The charges were dismissed four days after the arrest.11

Two months later, Bill was arrested for horse theft. A pair of stolen horses found at his livery implicated him in the crime. A thorough investigation proved that he had not been involved, as reported in the April 23, 1878, edition of the Ford County Globe.12

In the spring of 1877, he married Widow Flora Kendall and moved her and her baby to his Bluff Creek Ranch. Tilghman was now a respected family man and cattleman in Ford County. When Bat Masterson was elected sheriff of Dodge City in early 1878, one of his first orders of business was to hire Bill on as his deputy. In spite of Bill’s encounters with the law, he was certain the esteemed Tilghman would be a positive addition to the force. Bat knew about Bill’s reputation with a gun and his knowledge of Kansas and the surrounding territory. He also knew Bill didn’t drink, which meant there’d never be a question of alcohol affecting his judgment. “I’ve seen many a man get killed just because his hand was a little unsteady or slow on the draw, when he had a few drinks in him,” Bill maintained.13

Bill was dedicated to his position and approached his law enforcement duties, which included maintaining the office and records, feeding prisoners, and supervising of the jail, with quiet determination. He wasn’t content with solely keeping the peace; he wanted to know all about the legal process and proper methods of gathering evidence.

Unlike his mentor Bat Masterson and his idol Bill Hickok, who focused primarily on apprehending criminals using any means possible, Bill challenged himself to work within the confines of the law. Friend and foe alike appreciated his due diligence.14

In 1897, Flora Tilghman contracted tuberculosis and went to live with her mother in Dodge City. Her marriage to Bill had been strained for some years. Historical records indicate she didn’t care for Bill being a lawman. She was left alone a great deal. She didn’t like living in Oklahoma where Bill had taken a job as peace officer in the town of Perry. Flora filed for divorce shortly after returning to Kansas. She died three years later from tuberculosis. Flora and Bill had three children together, two girls and a boy. The oldest, Dorothy, was twenty when her mother passed away.15

Zoe and Bill met in 1900. Her father, Mayo Stratton, and Bill were friends. According to biographer Floyd Miller, “Zoe was not quite like any other girl he had ever known. She rode with the cowhands who worked her father’s ranch, wrote poetry, and had attended college.” Friends and neighbors described her as “a woman who could accomplish anything she set her mind to.” Zoe and Bill began corresponding while she was away at school in Norman, Oklahoma, studying to be a teacher. He proposed to her while she was home visiting her family over Christmas vacation in 1902, and they were married on July 15, 1903.16

After a brief honeymoon in Kansas City, Zoe moved into the home Bill had shared with Flora. Bill’s children resented their stepmother. Although she wisely did not try to come between them and their father, they never warmed to her. Dorothy especially felt the age difference between Zoe and her father was too great and believed this new woman in his life would eventually leave. The only thing that held them together was pride in Bill and the position he held in the county. According to Floyd Miller, “Bill was an influential man and was daily called up for advice on everything from family quarrels to business ethics.”17

In addition to teaching school, Zoe was an aspiring author of westerns. Her life with Bill offered great insight into the stories she wrote. It was a rugged, lawless time with numerous renegades roaming the region. Zoe noted in her memoirs that Bill slept with a loaded .45 under his pillow to protect his wife, and eventually the three sons they had together, from fugitives he had once arrested seeking to gun him down. “He was adept at shooting with either hand, but generally carried one six-shooter,” Zoe wrote in her biography about her husband. “Two were too heavy.”18

While Bill was making a name for himself defending the law, Zoe remained at home at their ranch in Lincoln County, Oklahoma, writing. She penned such published works as Sacajawea, The Shoshoni, Katska of the Seminoles, and Quanah the Eagle of the Comanche. The later book was the most well received of all the titles. She also authored western stories for periodicals such as Lariat Story Magazine and Ranch Romance.19

Zoe frequently wrote about her husband and the outlaws he apprehended. “He’s given much of the credit for breaking up outlaw gangs that overran Oklahoma in the 1890s,” she shared in articles she authored for the Ada Evening News. She bragged that he single-handedly took in Bill Doolin, a gang leader who swore he wouldn’t be taken alive, by beating Doolin to the draw. Tilghman was alone, too, when he captured Doolin’s lieutenant, Little Bill Raidler. He outshot Raidler with a double-barrel shotgun.20

In addition to being a peace officer, Bill served in the Oklahoma Senate. He was active in the statehood movement and Democratic policies, helped organize the first state fair and was an aide to many governors. By the time Bill was in his early seventies, he’d retired from law enforcement and was focusing on filmmaking. “He had a flair for making movies,” Zoe remembered in her memoirs. Between 1908 and 1915, he made four westerns.21

In August 1924, against Zoe’s objections, Bill came out of retirement to become city marshal of a booming Oklahoma oil town called Cromwell. It was here that he met his demise.

For a short while it appeared as if Marshal Tilghman was going to successfully reform the spot state investigators called “America’s wildest town.” “Cromwell – paradise of the oilfield huskies, is being cleaned,” the article on the front page of the Manitowoc Herald News read. “In this town of 300 persons, state agents claim they found wide-open gambling, 200 dope peddlers, and many dance halls in which girls danced for 15 cents a dance to the tune of weird jazz music, and “choc” beer was sold. Hijackers, bootleggers, and suddenly rich oil men played for high stakes around the tables in clapboard huts. One out of every three houses in town was a home of ill fame, state investigators contend.”22

“Federal officials have stepped in, drying up the town and breaking up the narcotic traffic. Then the governor and Judge Crump, backed by the businessmen, decided to hire Bill Tilghman as town marshal.”

“Though Bill is along in years he is just as ‘hard’ as he was in his younger days, the officials say. Bill has closed-up the saloons, a lot of the dance halls, and put the dope settlers on the run, in one week alone he and Deputy Sheriff Aldrich ushered 65 dancing girls out of town.”23

On November 1, 1924, a drunken prohibition officer named Wiley Lynn shot and killed Bill. Bill suspected Lynn of being corrupt and was in the process of gathering evidence to arrest him when he was slain. Lynn surrendered to authorities and admitted to the crime. He stood trial in federal court for the murder on May 20, 1925, and was acquitted. The jury found that his extreme drunkenness interfered with his judgment and exonerated him from the crime.24

Bill Tilghman was buried in Oak Park Cemetery in Chandler, Oklahoma. According to biographer Floyd Miller, “Zoe stood alone at his gravesite for a long while recalling the words her husband had spoken his last weekend home. She had urged him to set the date for his retirement and he had said, “Other men will set that date.”25

In tribute to her husband, Zoe wrote a book about the life of the intrepid, quick-drawing lawman in an almost lawless society. The book was entitled Marshal of the Last Frontier: The Life and Service of William Matthew Tilghman. Zoe died of natural causes in June 1964 and was buried next to Bill. She was almost eighty-four years old when she passed away.26

Love Lessons Learned by Zoe Agnes Stratton

1. Dazzle him with your smarts and be unique. Friends and neighbors described Zoe as being “unlike any other woman Marshal Tilghman had ever met.”

2. Appreciate his years of experience on the job and the job he wants to take on. Bill’s first wife would have preferred that he not had gone into law enforcement. Zoe objected only to the danger he exposed himself to and not the work itself.

3. Zoe was an author of western books and in many respects Bill was her muse. Being his wife’s inspiration endeared her to him.

4. Be willing to take to take on his family from a previous marriage. Zoe moved into the home Bill shared with his first wife and tried to make a life with his children, but they didn’t receive it well. Still, she tried.

5. Accept that justice needed a firm hand in the Old West and that your husband was that hand.