A wide variety of distribution companies, authors and press services attended the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association convention this weekend. Numerous book store owners, librarians, and book buyers for museums and special interest gift shops were on hand to learn about the new books being released and to stock up on material they know will sell at their businesses. My mission, in addition to signing books at the event, was to find out what does sell well. Big changes are transpiring in the publishing world. Many people are by-passing printed material and opting for books that can be read on their Kindles and I-Pads. I wanted to know where they predicted the market was headed. I did find out what books sell better than others and what book buyers are craving but more importantly I learned that nothing will ever take the place of good, old-fashion personal contact. Books are more likely to be carried at a store if the author reaches out to speak with the business owners and buyer. Owners of smaller book stores want to feel they matter as much as the chain stores. It’s interesting how it comes down to the simple art of consideration. All the advanced programs in the world won’t replace that. I was off to the airport after the event and while waiting for my flight I spent some time working on a letter to send lawyer I hired to represent my brother. I write him once a year on the anniversary of my brother’s sentencing. I can’t let there be a year go by without reminding this lawyer of what happened – even if he only considers it for a second or two. “Dear Mr. Hobbs, Six years have passed since you convinced me to persuade my brother to say he was guilty of a crime he didn’t commit. I’ll regret forever making him take a plea. I was told you were a defense attorney and I paid you an unimaginable fee for work in that area. I realized too late you do little more than negotiate plea agreements. If you had been forth coming with the truth at the start I would have been in a position to make a different decision. You were less than honest in your representation. I will always think of you as a disreputable man. Apart from my own ignorant actions in this matter, I recall your duplicity every time I see my brother’s bloated, broken face. I know you don’t but you should want to make this right.” My brothers are my brothers to the bone. Some of the booksellers I met this weekend who visit my website shared with me how well they think the book about Rick is going to do. It doesn’t really matter much to me anymore. He’ll still be just as gone and I’ll still be just as much to blame.

Writing the West

In the course of rewriting the Sam Sixkiller book I’ve neglected a host of things. Sleep, meals, answering the phone, answering the door, checking the mail… I continue to shower, although the big Texas hair has been shoved into a Dodge City baseball hat today and I am wearing my favorite perfume. What? Lancome Miracle goes well with jogging pants and a T-shirt. The deadline for the Sixkiller rewrite is October 31. I need to add 15,000 more words to the text. I know for sure that I like having written more than writing. I’m working on two other books in addition to the Sixkiller title too. And just when I think I can’t take on anymore until this deadline is met, I’ve got to travel to Portland, Oregon for a booksellers convention. It’s my own fault. I over commit. I started this insane schedule years ago when Rick was raped during a prison transfer. I couldn’t close my eyes without seeing him being beaten and hurt. I’ve created this mess and I just have to ride it out now. Within the last month I received word that I am now an official member of the Western Writers of America. I can’t help but think that might a mistake. I’m just an author that likes to research and write about the history I find. The majority of the people involved in Western Writers of America are scholars and award winning authors of historical events. I have a feeling I’m in way over my head. I will be attending the convention the group hosts in the fall of next year in New Mexico, but know I’m going to feel wildly out of place. I hope it will be a good education. The collection of professionals that attend these events are impressive. I just don’t want to be treated like a bastard at a family reunion. With the exception of my involvement with the Single Action Shooters Society, I’ve never experienced anything but that kind of treatment when I’ve joined writers groups. Will Rogers once said, “Everybody is ignorant, only on different subjects.” When I attend the WWA convention I’ll be the only one in the room ignorant on every subject. I can’t tell. Are my insecurities showing? I can’t worry about that now I guess. I’ll worry about that tomorrow. Right now it’s back to Oklahoma to find more Sam Sixkiller adventures.

Cherokee Lawman

It is said that “change is inevitable – except from a vending machine.” Often times I think I’m just as stubborn with change as a vending machine. The website has been changed but the sentiment in the daily journal will remain the same. I miss my brother and will probably always write about that. He has value. I won’t forget him and I’ll fight to my death to never let those who falsely accused him forget him either. Oh, the sharp knife of a short life. Three very good friends of mine – Chris Frank and Tim and Joyce Smethers – lent a hand with the new video posted on the site. It was a wonderful learning experience and the closest I’ll probably ever come to being in a real western. Thanks to Chris and the Smethers for helping to check an item off the bucket list. I’ve been working day and night on the edits for the Sam Sixkiller book. The deadline is October 31. What a pleasure it has been to write about such a great lawman. I’m amazed at how fearless his was in the face of notorious bad guys like Dick Glass and Alf Cunningham. The book about this courageous Cherokee Indian will be in bookstores June 2012.

Walter Hill & Howard Kazanjian

I traveled to Los Angeles yesterday to meet with director Walter Hill about writing the screenplay based on the book Thunder Over the Prairie. Mr. Hill is currently editing the latest film he directed starring Sylvester Stallone. The film will be released in April but the talented writer/director believes he can get the script written before the Stallone picture comes out. It was quite an experience having lunch with two motion picture icons – Walter Hill and Howard Kazanjian. I was glued to their conversation about the western movies they’ve made from The Wild Bunch to The Long Riders. Sometimes it seems I’m so busy trying to get a moment like that I don’t realize that it’s happening when I’m in it. Yesterday was the exception. I listened intently as they spoke of shooting the film Geronimo in Moab, Utah and The Wild Bunch in Mexico. They talked about some of motion picture’s greatest actors such as Alan Ladd. Mr. Hill shared a story about Ladd’s comments as he completed filming a sequence in the western Shane. Ladd walked off the set and someone asked him how he thought he did that day and Ladd responded with “I got a few good looks in.” It’s important to look like a cowboy who means business in westerns and evidently Ladd and Jack Palance were two of the best at that. No matter what strides are made in this movie making venture and how exciting it can be at times, my thoughts always go back to my brother Rick. It seems he might be allowed to get help for his eyesight soon. I can be happy and thankful for the opportunities I get to discuss western films with award winning industry folks but I’d trade all those chances and any chance I might ever get at success for my brother to be home and well again.

Gold Rush Women & Tom Bell

I live in the midst of a peaceful forest in Northern California. Very earlier in the morning all that can be heard is the sound of the creek below racing to its natural end and the owls gently calling out to one another from one end of the dense oak trees to the other. It’s the perfect time to reflect on the settlers who arrived at this spot more than one-hundred and fifty years ago. I consider the strength of pioneer women like Nancy Kelsey and Luzena Stanley Wilson. They came into the Gold Country with a dream for a better life and were determined to find it. They wanted to make a difference for their children and their children’s children and they did. Nancy was the only woman with the Bidwell-Bartleson wagon train. She made the journey here from Independence barefoot and carrying a one year old baby on her hip. The men in the party noted in their journals that whenever they felt they couldn’t go on they would look back at Nancy and gain the strength to continue on. Luzena arrived here with three children and the basic necessities to set up camp. Her husband left her alone to fend for herself while he went in search of gold. By the time he had arrived back to the make-shift home Luzena had opened a small restaurant and was selling her tasty biscuits to hungry miners. In the end she made more money than her spouse ever dreamed of finding panning for gold in the cold streams at the base of the Sierras. As you probably noticed the website has been updated. With that comes the great desire to update the content I’ve been pouring into the journal pages. As long as my brother suffers behind bars and my family is scrutinized so vigorously I don’t suppose I’ll be able to entirely leave the subject. It will find its’ way into my writing more often than not but my goal is to share more about how women influenced the west and how the impact of what they did is still felt today. I’ll still be writing about some of my favorite western characters but will add tales of the lesser known people who helped settle the frontier. Since I’ve already mentioned the Gold Country that spot of land between Sacramento and Lake Tahoe it seems fitting to write about a notorious criminal from these parts. It was on this day in 1856 that the outlaw, Tom Bell, was captured by vigilantes on the Merced River in Northern California. They patiently allowed him to write letters to his mother and his mistress and then strung him up. Bell was known as the “Gentleman Highwayman.” His true name was Thomas J. Hodges. He was a native of Rome, Tennessee, where he was born about 1826. His parents were most excellent, highly respected people, and gave young Hodges a thorough education. He graduated from a medical institution and, shortly after receiving his diploma, joined a regiment and proceeded to the seat of war in Mexico, where he served honorably as a non-commissioned officer until the close of the struggle. Like thousands of others, he was attracted to California by its golden allurements, and began life here as a miner. Evil associates, coupled with lack of success, caused him to follow in the footsteps of many, whose loose moral ideals led them into gambling as a means of subsistence. Soon tiring of this, he took to the road, where he continued his game of chance in a tenser setting, staking his revolver against whatever loose coin his victims had about them. He formed a band of desperados called the “Tom Bell Gang” and for nearly two years kept the State in a fever of excitement. Finally, his dishonest ways caught up to him. The lies he told were revealed and he was strung up for his misdeeds. That’s the way it should be. The way it ought to be, regardless of the sex of the criminal.

The Ballad of Frankie Silver

The Richmond Timed Dispatched called author Sharyn McCrumb’s book “a novel of mesmerizing beauty and power.” I was captivated at how McCrumb tied two stories together in one novel – set apart by at least a hundred and twenty years. This book starts out with sheriff Spencer Arrowood recovering from a shotgun wound, and his recollection of sending a young man to death row. Fate Harkryder was accused of murdering a young couple in such a heinous way that in spite of his claims of innocence, no one believed him in their rush for justice. While Arrowood is recovering, he finds himself intrigued with the case of Frankie Silver, a young mother who was accused of murdering her husband and butchering his body so that there’s three grave sites for him. McCrumb writes in great detail of Frankie’s trial, observed by the young clerk of court, Burgess Gaither, who tells her tale so vividly that I actually broke down in tears at one point. And Arrowood rushes to find out who really did murder the young college couple that fateful night, twenty years ago, Fate or someone else?

The stories of Fate and Frankie are tied up beautifully and examines the strength of family ties that bind even in death. This is one of the most provocative novels I have read in a long time. It addresses the legal system (which is deeply flawed as portrayed in this novel) and the issue of capital punishment. It is definitely a worthwhile read.

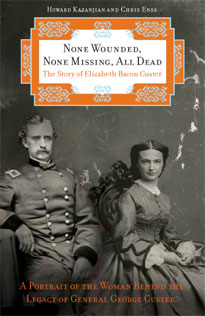

None Wounded, None Missing, All Dead Available in Paperback Winter 2012

On May 17, 1876, Elizabeth Bacon Custer kissed her husband George goodbye and wished him good fortune in his efforts to fulfill the Army’s orders to drive in the Indians who would not relocate to a reservation. The smartly dressed couple made for a splendid picture. This new biography of Elizabeth Bacon Custer tells the story of the dashing couple’s romance, reveals their life of adventure throughout the West during the days of the Indian Wars, and recounts the tragic end of the 7th Cavalry and the aftermath for the wives. Libbie Custer followed her itinerant army husband’s career to its end—but she was also an amazing master of propaganda who sought to recreate George Armstrong Custer’s image after Little Bighorn. Famous in her own time, she remains a fascinating character in American history.

Watch the Trailer

Elizabeth Custer’s Life Without George

An Excerpt From Tales Behind the Tombstones

Carrie Nation

“Men are nicotine-soaked, beer-besmirched, whiskey- greased, red-eyed devils.”

Carrie Nation – 1887

The barroom at the Hotel Carey in Wichita, Kansas was extremely busy most nights. Cowhands and trail riders followed the smell of whisky and the sound of an inexperienced musician playing an out of tune piano inside the saloon. Beyond the swinging doors awaited a host of well-used female companions and an assortment of alcohol to help drown away the stresses of life on the rugged plains. Patrons were too busy drinking, playing cards or flirting with soiled doves to notice the stout, 6 foot tall woman enter the saloon. She wore a long black alpaca dress and bonnet and carried a Bible. Almost as if she were offended by the obvious snub, the matronly newcomer loudly announced her presence. As it was December 23, 1900, she shouted, “Glory to God! Peace on earth and good will to men!”

At the conclusion of her proclamation she hurled a massive brick at the expensive mirror hanging behind the bar and shattered the center of it. As the stunned bartender and customers looked on, she pulled an iron rod from under her full skirt and began tearing the place apart.

The Sheriff was quickly sent for and soon the violent woman was being escorted out of the business and marched to the local jail. As the door on her cell was slammed shut and locked she yelled out to the police, “You put me in here a cub, but I will go out a roaring lion and make all hell howl.”

Carrie Nation’s triad echoed throughout the Wild West. For decades the lives of women from Kansas to California had been adversely effected by their husband’s, father’s and brother’s abuse of alcohol. Carrie was one of the first to take such a public, albeit, forceful stance against the problem. The Bible thumping, brick and bat wielding Nation was a member of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. The radical organization, founding in 1874, encouraged wives and mothers concerned about the effects of alcohol, to join in the crusade against liquor and the sellers of vile drink. Beginning in 1899, prior to Carrie’s outbursts, the group had primarily subscribed to peaceful protests.

Carrie was born Carrie Amelia Moore on November 25th 1846 in Garrard County, Kentucky. Her father was an itinerate minister who moved his wife and children from Kentucky to Texas, then on to Missouri and back again to Kentucky.

Carrie married for the first time in 1866. Her husband was a heavy drinker and after their wedding she pleaded with him to stop. After six months of persistent nagging, Carrie’s spouse still refused to give up the bottle. With a child on the way she left him and returned home. He died of acute alcoholism one month before his child was born.

Not long after her first husband passed away, Carrie married again. David Nation possessed the same love for alcohol as did the father of her son. He was a lawyer and a minister who did not share in what he called “his wife’s archaic view” about liquor. Their differences of opinion not only interfered with their personal life, but reeked havoc on David’s professional life as well.

The Nations moved to Texas and Carrie immediately joined the Methodist church. Her outlandish beliefs and revelations prompted the members of the congregation to dismiss her. Carrie then formed her own religious group and held weekly meetings at the town cemetery. In 1889, Carrie insisted that David move her and their children to Medicine Lodge, Kansas. Kansas had a prohibition law and Carrie believed the fact that liquor was outlawed would stop David from partaking of any libations.

Determined Kansas residents found ways to drink and so did Reverend Nation. Drug stores and clubs sold whisky in backrooms and alleys, calling the liquid medicine instead of alcohol. Carrie was outraged. Not only did she chastise members of her husband’s assembly in Sunday service, but she scolded those she knew drank when she saw them on the street.

Carrie believed the Lord had called her to take such drastic action against alcohol. According to her autobiography, The Use and Need of the Life of Carrie Nation, she felt it was her duty to defend the family home and fight for other women locked in marriages with excessive drinkers.

At the age of 53, she marched into a drug store on the main street of Medicine Lodge and preached the evils of drink to all the customers. She was tossed out of the business, but a crowd of women who had gathered to inquire about the excitement applauded her efforts. Their response and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union members spurred her on. She continued to visit liquor stores until all the bars in town were effectively forced to close.

Carrie waged a one woman campaign against saloons across Kansas and into Oklahoma.

There were times she entered barrooms with a hatchet and smashed tables and bottles of beer. She was arrested on numerous occasions and spent several nights in jail. Her demonstrations made the front page of newspapers from Boston to Independence. She was recognized as a heroine by women everywhere and hailed as a courageous fighter for the cause.

David Nation was unimpressed with his wife’s devotion and tried to convince her to abandon the quest and settle down. She refused and sued for divorce. She turned to the lecture circuit as a way to support herself and her children. Her following was substantial, but when she took to appearing in Vaudevillian style shows and selling souvenir hatchet pins, many of her supporters turned against her. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union had a change of heart about her as well and withdrew their endorsement of her.

The last public assault Carrie waged on a tavern occurred in Butte, Montana in January 1910. Her hatchet was poised to do damage, but the owner of the business, a woman named of May Maloy, stopped her before she could strike a blow. Not long after the humiliating incident, Carrie retired from hatchet marching and dedicated herself strictly to speaking engagement.

She passed away on June 9, 1911, after collapsing during a speech at a park in Eureka Springs, Arkansas. She was buried at the Belton City Cemetery in Belton, Missouri, a location where she had spent a great deal of time in the final days of her life. The tombstone over her grave, erected by the Women’s Christian Temperance Union reads, “Faithful to the Cause of Prohibition, She Hath Done What She Could.” She was 65 years-old when she died.

An Excerpt From The Young Duke

Shy, thoughtful, overly generous, modest and compassionate – this doesn’t describe the John Wayne most people remember from the very public person he projected in the 1960s and 70s, when his body of work was filled with tough-talking, aggressive, out-for-justice characters. But articles and interviews done with him early in his career suggest John Wayne grew up as a not-so-confident, no-so-outspoken young man.

He rode into the motion picture realm in 1930 with a purposeful swagger and a hard, no-nonsense manner of speaking that epitomized the American cowboy. When the 23 year-old hard fisted, quick-shooting, daredevil accepted a summer job at Fox Films, three years prior to his first starring role in The Big Trail, he could not have foreseen the impact he would have on the film industry. After five decades in the business the gallant 6’2 actor would brand movie going audiences with an indelible image and would forever be recognized as a sagebrush hero.

Born on May 26, 1907, in Winterset, Iowa he was given the name Marion Michael Morrison. When he was seven his parents left the Midwest and moved to a ranch in the Mojave Desert in California.

Marion spent a great deal of time outdoors, hiking through the valley and teaching himself to ride one of the two plow horses his father owned. Just as the young boy was adjusting to life in the rural area his folks relocated to Glendale.

According to an interview Wayne did with Motion Picture Magazine in February 1931, his parents were an unhappy couple and had frequent and heated arguments. He avoided the disharmony by staying away from home. A busy young boy, he got a part time job delivering medicines and supplies for the pharmacy where his father worked and joined the Boy Scouts and YMCA.

A bit of a loner, he spent long hours exploring the neighborhood with his Airedale, Duke. The firefighters Marion befriended in the area referred to the boy as Big Duke and the Airedale as Little Duke. The nickname stuck, and his given name Marion, which he had always disliked, was replaced with one more fitting his independent personality.

Duke did extremely well in school and was involved in numerous extra-curricular activities. He was an exceptional football player, class president and a member of the drama club. In addition to his studies and athletic pursuits, Duke kept up with his various part time jobs. One of which was delivering handbills for the Palace Grand Movie Theatre. When he wasn’t at school or work he was at the Palace.

Three or four times a week Duke would escape into the world of motion picture cowboys and Indians by watching films starring his idols, Tom Mix and Harry Carey. His appreciation for the actors and the art form grew until he was no longer content to simply enjoy the finished movie. Duke wanted to know how motion pictures were made and decided to venturing onto the lot of a silent-movie studio called the Kalem Motion Picture Company. Many well-known stars of the time like Douglas Fairbanks Jr. and Helen Holmes worked at the studio. Duke was enamored with the process – the actors, set directors, camera operators and stunt performers.

Although young Duke Morrison’s had a keen interest in filmmaking his life’s ambition was to serve in the military. He was bitterly disappointed when his application to the Naval Academy was denied in 1925. A football scholarship to the University of Southern California momentarily shifted his focus off his misfortune. He tackled this new direction with gusto and verve, extensively training for games with Trojan’s coach Howard Jones.

Off of the football field, Duke was a popular student who thrived on the camaraderie of his fellow class and teammates.

He was handsome, smart and easy to get along with and whether he was attending an event at the fraternity he belonged to, or working at one of the two jobs he had to help pay his living expenses, Duke was happy. The pleasing lifestyle he enjoyed at college was in stark contrast to the tense and distraught existence he had staying with his parents. Their relationship continued to be combative and after more than 20 years of marriage, the pair decided to go their separate ways.

In 1927, at the age of 20, he would be denied another career opportunity. A severe shoulder injury sidelined the college sophomore an eventually cost him a place on the USC team and his scholarship. Once again the tenacious Duke had to make a shift in his pursuit. It was time to see if he could make a living in the movie industry he admired.

During his freshman year in college, cowboy actor Tom Mix had offered Duke a part time job at Fox Films Corporations. He worked in prop department and was considered by many of the top directors at the time to be one of the best “prop boys” in the business. A prop boy’s job was to see to it that every item an actor is required to handle in a scene is available when the director wants it.

Duke was good at his job because he could anticipate what a director would need and if the item wasn’t available, he would nail, whittle or weld a reasonable facsimile before anyone found out.

Mix felt that Duke had a future in front of the camera as well as behind. “He had shoulders like the Golden Gate bridge and the kind of pale blue eyes you find in a long riding cowboy,” Mix told Fox executives. He had Duke cast as a bit player in a few of his films and on occasion hired him to work as a stuntman. Duke had a natural aptitude for the job and wasn’t afraid to take risks to achieve the effect the directors called for.

A supporting role seemed to fit Duke just fine. He didn’t deliberately strive to be an adored movie star, but if Duke was not pursuing stardom, others saw greater roles in his future.

John Ford was the first to appreciate Duke’s physical courage on the set. During the filming of “Men Without Women” Ford hired Duke to act in the movie and used him as a stunt double as well. The script called for several sailors, trapped in a doomed vessel, to escape their death by being shot out of the torpedo tubes.

Trained divers were on hand to rescue the actors once they made it to the surface, but still the men playing the sailors refused to take part in the stunt because the conditions of the water off the coast of Catalina were too dangerous. Ford disregarded their warning and prevailed upon Duke to do the stunt. Duke eagerly obliged.

Content to work in the prop department and with no thought of ever being a screen legend, Duke accepted offers to appear in a variety of low budget films. His passion for film acting and stunt work grew and although John Ford had assured Duke his first shot at a starring role, it was director Raoul Walsh who made that happen. Walsh was searching for a tough, good-looking lead for a Western he was making called The Big Trail. Duke had all the qualities necessary for the part, but before the studio would hire him on they insisted he change his name. Fox executives selected a handle they felt sounded rugged and captured the essence of an American cowboy. Duke Morrison, now known as John Wayne, galloped into theatres on October 2, 1930.

The Big Trail was not a huge money maker for the studio, but John Wayne’s performance did not go overlooked.

Fox Films signed him as a regular contract player and for nine years Wayne twirled six guns, tossed rope, busted broncos and foiled cattle rustlers in a series of low-budget, quickie westerns. During that time he honed his skills as a stuntman, training with one of Hollywood’s finest stuntmen, Yakima Canutt. Canutt was a rodeo champion turned actor who was known for his amazing leaps from and onto horses and wagons. Together the two created a technique that made on-screen fight scenes more realistic.

By the time John Ford offered Wayne the part of John Ringo in the movie Stagecoach, the Duke had made more than 80 films and was one of the top sagebrush heroes of the screen. Stagecoach was released in March 1939 and received glowing reviews. The critics singled out Wayne’s performance, praising him for his fine and memorable work. The film changed the course of Wayne’s career and did the same for westerns as a film genre.

After the success of Stagecoach, the battle-scarred veteran of the B-Western was given the opportunity to make other pictures outside that of horse operas. Instead of searching out a big-budget movie to boost his popularity, Wayne trusted his career to his mentor, John Ford.

In 1940, he again worked with Ford, this time he played a sailor on a tramp freighter who is drugged and shanghaied in Eugene O’Neill’s dreamy tragedy, The Long Voyage Home. Wayne’s strong performance proved that he had range as an actor and reassured filmmakers that he could handle new roles.

During this time Duke was paired with some of Hollywood’s most compelling leading ladies – Marlene Dietrich, Paulette Goddard and Clair Trevor were among his costars. The on-screen chemistry he shared with those starlets and his versatility made films like Reap the Wild Wind, Dark Command, and A Lady Takes a Chance classics.

From 1943 to 1945, Wayne alternated between appearing in westerns and war epics, forever solidifying his film persona as a stalwart soldier and a champion of the range. His portrayal of Sergeant Stryker in Sands of Iwo Jima earned him an Academy Award nomination and his work in She Wore A Yellow Ribbon was hailed by critics as “spectacular and noble.”

One of the most challenging cowboy roles Wayne ever took on was that of Thomas Dunson in Red River. After seeing the movie, Ford admitted that he had underestimated Duke’s capabilities. He told Daily Variety magazine, “I didn’t know the son-of-a-bitch could act.”

Ford rewarded Duke’s efforts in Red River with an offer to play the lead in another western. The movie promised to be a wide cut above the average cowboy film, depending on human relationships for its value as well as on the customary chase.

The complex part had the potential of further enhancing Wayne’s career. On the other hand, the near villainous role of Ethan Edwards in The Searchers could threaten his top box office status. Wayne took a chance that the film and his performance would be well received by moviegoers who saw him not only as an actor, but a larger than life hero.

The Young Duke: The Early Life of John Wayne is available at bookstores everywhere.

Thunder Over the Prairie

The year was 1878. Future legends of the Old West–lawmen Charlie Bassett, Bat Masterson, Wyatt Earp, and Bill Tilghman–patrolled the unruly streets of Dodge City, Kansas, then known as “the wickedest little city in America.”

When a cattle baron fled town after allegedly shooting the popular dancehall girl Dora Hand, these four men–all sharpshooters who knew the surrounding harsh, desertlike terrain–hunted him down, it was said, like “thunder over the prairie.” The posse’s legendary ride across the desolate landscape to seek justice influenced the men’s friendship, careers, and feelings about the justice system. This account of that event is a fast-paced, unforgettable glimpse into the Old West.

Interview

Listen to an interview from Chronicle of the Old West

Photos

Photos from the Thunder Over the Prairie

book launch in Dodge City, Kansas