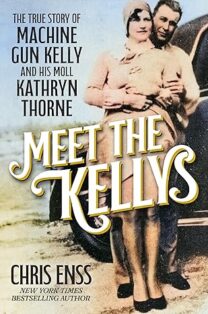

Enter now to win a copy of

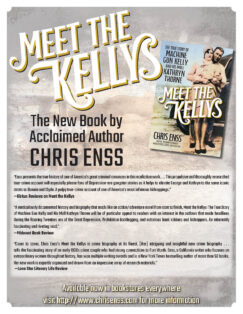

Meet the Kellys:

The True Story of Machine Gun Kelly and His Moll Kathryn Thorne

“Going to see Bonnie and Clyde at a local drive-in was the start of my interest in the Great Depression and that era’s gangsters. Bonnie and Clyde. Pretty Boy Floyd. John Dillinger. Ma Barker. Bugs Moran. I’m not quite sure why I found these gangsters to be so fascinating. I didn’t think they were romantic. I certainly didn’t want to emulate them. I think it probably had something to do with how people reacted to and survived the Great Depression. So, it’s no wonder that when I heard about Meet the Kellys that I wanted to read it.

I was familiar with other books written by Chris Enss, so I was expecting a well-researched history of Kelly and Thorne. That’s exactly what I got. Kathryn Thorne saw the potential in small-time bootlegger George Kelly to give her the lifestyle she had always craved. And with her gift of a machine gun to Kelly, history was made. The couple’s endless road trips not only had me hearing some of the music from Bonnie and Clyde, but they almost made me carsick.

I learned quite a bit from this book. I’d forgotten how kidnapping had taken center stage for several of these gangsters, so much so that the government passed the Federal Kidnapping Act in an attempt to put an end to it. In true diva style, when everything disintegrated, Kathryn Thorne tried her best to keep herself and her parents out of jail. She was definitely what my family would refer to as a “piece of work.” If you have any interest at all in this time period, Meet the Kellys is well worth a read.” Kittling Book Reviews

Meet the Kellys

I'm looking forward to hearing from you! Please fill out this form and I will get in touch with you if you are the winner.

Join my email news list to enter the giveaway.

"*" indicates required fields

Meet the Kellys

I'm looking forward to hearing from you! Please fill out this form and I will get in touch with you if you are the winner.

Join my email news list to enter the giveaway.

"*" indicates required fields