Enter now for a chance to win the book

High Country Women: Pioneers of Yosemite National Park

Celebrate the 126th anniversary of Yosemite!

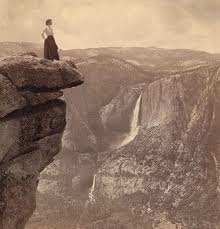

Yosemite’s Half Dome, the hooded monk in stone, brooding over its eastern end, rises thousands of feet from the ground below, so high that its summit is wreathed in clouds. In October 1876, three men scaled the mountain face slowly working their way to the top. All were dressed in woolen caps and trousers, thick coats and gloves, and leather boots. Scotsman George Anderson, a former sailor and carpenter working in Yosemite Valley as a blacksmith and surveyor, led the way up the massive rock. The confident manner in which he ascended the mountain suggested he was a seasoned climber. Author Julius Birge followed closely behind George, his face a mask of strained concentration and worry that confirmed he was a novice at climbing. Occasional gusts of wind tried to knock the men off balance, but they persevered, finding finger hold after finger hold, and finally pulling themselves onto a ledge at the top. The second adventure seeker with the party proceeded behind him trying to regain his strength.1

Resting on the summit, the men stared out over the valley admiring the scenic grandeur. Yosemite Valley had an average width of half a mile. The great walls of the canyons all around them were seamed by water-worn fissures, down which rivers leapt, thundered, churned, and sang with all possible variations and expressions of sound.2

In his memoirs entitled Awakening in the Desert published in 1912, Julius described the process of arriving at the top of Half Dome. “Anderson had spent the summer drilling holes into the granite face of the upper cliff,” he wrote. “Driving in it iron pins with ropes attached. Two or three were tempted to scale with the aid of these ropes the heights which are nearly a perpendicular mile. I, too, was inclined to make the venture. It was a dizzy but inspiring ascent.”3

After more than an hour at Half Dome’s Summit, catching his breath and preparing himself for the desert, Julius found an unusual item on the rocks. “I discovered on its barren surface a lady’s bracelet,” he recalled in his book. “On showing it to Anderson, he said: You are the third party who has made this ascent. I pulled up a young woman recently but she never mentioned any loss except for nausea. Returning to Merced, I observed a vigorous, young woman wearing a bracelet similar to the one I found. The lady proved to be Miss Sally Dutcher of San Francisco, who admitted to the loss and thankfully accepted the missing ornament. A letter to me from Galen Clark (Yosemite resident, businessman, and explorer) stated that he assisted in Miss Dutcher’s ascent, Anderson preceding with a rope around his waist connecting with Miss Dutcher; also that she was certainly the first and possibly the last woman who made the ascent.”4

Although the exact date is not known, Sarah Louisa Dutcher was the first woman to make her way to the top of Half Dome. Historians believe the intrepid young woman accomplished the feat in 1875.5 According to James Hutchings, a British journalist who traveled to Yosemite and wrote about his experiences, “Miss S.L. Dutcher was the first lady that ever stood upon the mountain. George Anderson was one of the first human beings to ascend Half Dome and his efforts made it possible for others to follow.” “In preparation for the climb,” James wrote in his memoirs, “Anderson’s next efforts were directed toward placing and securely fastening a good, soft rope to the eye-bolts, so others could climb up and enjoy the inimitable view, and one that has not its counterpart on earth. Four English gentlemen, then sojourning in the valley and learning of Mr. Anderson’s feat, were induced to duplicate his intrepid example. A day or two afterwards, Sarah Dutcher, with the courage of a heroine, accomplished it.”6

To learn more about Sally Dutcher and Lady Jane Franklin

and the other women who helped make Yosemite a National Park read

High Country Women: Pioneers of Yosemite National Park