Enter to win a copy of

Entertaining Women: Actresses, Dancers, and Singers in the Old West

Winners will be announced on February 28, 2016

Long before actors were vying for an Oscar nomination and world wide fame thespians were trying to carve out a modest living entertaining prospectors and settlers of the Old West. Today the curtain goes up on a woman entertainer who captured the hearts of the western pioneers.

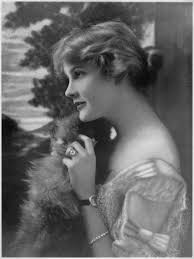

Ladies and gentlemen, Jeanne Eagels, the Forlorn Leading Lady

Triumph and tragedy, alternating strangely throughout her life converged on the night on October 3, 1929, when Jeanne Eagels, beautiful and famous actress, suddenly collapsed and died. At a time when her health seemed much improved and she was planning a comeback to the Broadway that had barred her for eighteen months, the black curtain descended noiselessly and swiftly.

It brought to an end the drama of a woman who had made a sensational rise to the heights of theatrical stardom, a woman men clamored for and loved, perhaps too well. Romance, broken hearts, success and defeat, adulation and repudiation – a pageant of experiences and emotions – had paraded through her life. And in the end Jeanne Eagels was the same woman she had been years before – a proud, tempestuous spirit seeking bewilderingly for some distant horizon of happiness.

On her last day alive it probably did not seem to her that death was in the wings. If so, it made no difference. For that night she dressed in her most elaborate and beautiful clothes. She was planning to join a Broadway party. Broadway! The street which soon, she thought, would once more echo to her name and where incandescents would spell it out in glittering letters.

But hardly had she dressed when she suddenly fell faint. The night before she had taken an overdose of a solution of a sleep-producing drug called chloral hydrate. She was rushed from her Park Avenue home to a private sanitarium. They brought her into a room for an examination. She sat on the bed a moment, and then wearily took off her coat. It revealed her in all her glory. Jewels shone magnificently. Diamonds and pearls sparkled on her fingers, about her neck and on her wrist.

She signed. There was only a nurse to see this last act. She sank on the bed in convulsions. A little later she was lifeless. And then Broadway and the whole world learned with astonishment of her sudden passing.