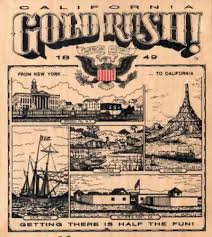

Many elementary schools across the country are now studying the California Gold Rush. This short, continuing story is intended to aid teachers in their efforts to share with their classes the significance of this historical events. Teacher who use the story in this week’s lessons can register to win a copy of the book Frontier Teachers.

James Marshall stood up and saw his laborers sitting around their fire drinking coffee and eating flapjacks. Beyond them the Indian workers moved quietly, preparing their breakfast of dried deer meat. Marshall walked slowly to the fire where his sober Mormon workers ate silently, and opened his hand.

“I found it in the tail race.”

The men stopped chewing and one exclaimed, “Fool’s gold,” and laughed. Another spit carefully into a bush several yards away. “Tain’t nothing by iron pyrite,” he said. “Fool’s gold, that’s all.”

The first man took a closer look, reached for another flapjack, and said, “That’s right. That stuff fools lots of people.” They all grinned knowingly at each other.

James Marshall scowled and clenched his fist over the little pebble. They thought him a fool. He turned on his heel, and strode up the slope to a small log cabin where smoke was lazily rising from an adobe chimney. As he approached he saw Elizabeth Wimmer, wife of his foreman, standing with a long stick in hand over a big, black soap kettle. Elizabeth Wimmer was one of the few American women in this land so lately taken from Mexico. She had refused to be left at Sutter’s Fort when Peter, her husband, went to take charge of the Indian laborers building the sawmill.

As Marshall came up to her he growled, “Look here, Mrs. Wimmer! This looks like gold. The men say it’s iron pyrite.” He unclenched his fist.

Mrs. Wimmer leaned forward curiously. Then, before he could stop her, she picked up the little piece and dropped it into the bubbling soap kettle. “We’ll soon find out, Mr. Marshall. If it isn’t gold the lye in this kettle will eat it up quick.”

James Marshall said nothing, but turned and went back to the breakfast he had not yet eaten.

That night as he went to the cabin where he lived with the Wimmers he felt confident again. The mill would work well with the tail race deepened. He was thinking of the lumber they would soon be sawing and of the money they could get for it in the sleepy village of San Francisco. As he sat and smoked his pipe he was startled by Mrs. Wimmer. Through the door she marched, and up to the scrubbed pine table.

“There!” she cried triumphantly. “It’s gold, all right, Mr. Marshall!”

She flung on the table the heavy little stone. In the light of the candle it glowed and gleamed. Marshall picked it up, then put it on the floor, grasped a rock lying by the hearth, and hammered it. It didn’t break. Gold!

Next morning at dawn he went back to the tail race. From cracks between the boulders he picked up more of the tiny gold pieces. Carefully he stowed them away in a small buckskin bag and went back to his job of getting the mill going. Later in the day he announced to Peter Wimmer:

“Supplies are getting low. I’m going to the Fort for grub. Wimmer, you take over while I’m gone.”

Peter Wimmer glanced at his wife, but said nothing.

Register now to win a copy of the book Frontier Teachers.