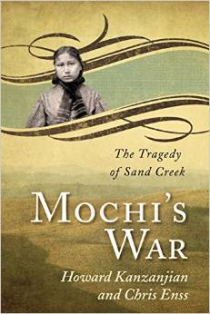

It’s time to enter to win a copy of Mochi’s War: The Tragedy of Sand Creek.

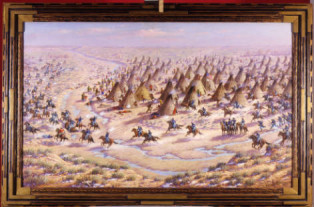

At daybreak on November 29, 1864, the sound of the drumming of hooves on the sand flats interrupted the hushed routine of the Indian women and children. Some of the women believed it was only buffalo running hard in the near distance, but it was Col. John Chivington and his men and they had come to attack and kill the Cheyenne in the camp.

Mochi was among the numerous Indians frantic to escape the slaughter. She watched her mother get shot in the head and heard the cries of her father and husband as they fought for their lives. Mesmerized by the carnage erupting around her, she paused briefly to consider what was happening. In that moment of reflection one of Chivington’s soldiers rode toward her. She stared at him as he quickly approached, her face mirrored shock and dismay. She heard a slug sing viciously past her head. The soldier jumped off his ride and attacked her. Mochi fought back hard and eventually broke free from the soldier’s grip. Before the man could start after her again she grabbed a gun lying on the ground near her, fired, and killed him.

To learn more about Mochi read Mochi’s War: The Tragedy of Sand Creek.