Enter to win a copy of How the West Was Worn:

Bustles and Buckskins on the Wild Frontier

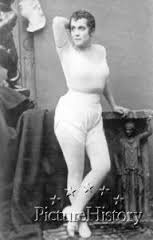

Amelia Bloomer modeling a pair of world famous bloomers.

Elizabeth “Baby Doe” Tabor was one of the Old West’s legendary trendsetters. The Colorado socialite had golden hair, blue eyes, porcelain skin, and a sense of style that rivaled that of any woman in Leadville. She arrived married to a struggling miner but dressed like she was the belle of the ball. She paraded down the main street of town wearing a sapphire-blue costume with dyed-to-match-shoes. Her stunning style caught the attention not only of neighbors and storekeepers but also of millionaire Horace Tabor. Horace and Elizabeth scandalized the community by falling in love, divorcing their spouses, and marrying one another. Horace showered his new bride with jewels and the finest outfits from Boston and Paris. She wore one-of-a-kind outfits to opening nights at the opera house he had built for her.

All eyes were on the young Mrs. Tabor as Horace escorted his young bride into the theatre. Her dresses were made of Damasse silk, complete with a flowing train made of brocaded satin. The material around the arms was fringed with amber beads. The look was topped off with an ermine opera cloak and muff. Pictures of the Tabors appeared in the most-read newspapers, and soon, women from San Francisco to New York copied the outfit. The only part of the costume admirers were unable to reproduce to their satisfaction was Mrs. Tabor’s $90,000 diamond necklace.

To learn more about the trendsetter of the Old West read

How the West Was Worn: Bustles and Buckskins on the Wild Frontier