From Child Star to Beloved Actress

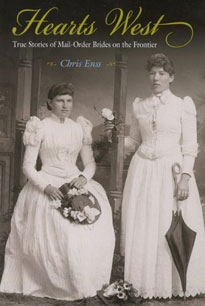

Maude Adams in The Masked Ball.

The Palmer Theatre House in New York was jammed to the doors by a curious clientele all there to see the new actress working opposite the most celebrated actor of the day, John Drew. It was October 3, 1892 when the stunning, elfin-like Maude Adams took to the stage in the play “The Masked Ball.” At the end of the evening Drew would be congratulated on his admirable acting job, but Maude would score a hit that would be greater than his entire career. Her performance was so successful the applause lasted for a full two minutes after she made her exit. She was on her way to becoming a star and local newspapers predicted her talent would be talked about for years to come.

Maude Adams’s stage career began at the tender age of nine months. The play was called “The Lost Child” and the baby that was playing the lead became fussy and could not continue in the show after the first act. Maude’s mother, Annie, who was the female lead in the production, suggested her daughter take the child’s place. Maude was so good that the other baby received her two weeks’ notice immediately after the play ended. For the remainder of that season all the infant roles were played by little Miss Maude.

Maude Ewing Adams Kiskadden was born on November 1, 1872 in Salt Lake City. Her mother, Annie, was a leading lady in the stock company that played in the local Social Hall. Her father James Kiskadden worked for a bank and also in the Alta mines. Although Maude had been quite a success as a baby actress, James was reluctant to allow his daughter to go into the theatre. “She’s my only daughter,” he told his wife. “And I’ve no intention of letting her go on the stage and make a fool of herself.“ Now five years of age, Maude informed her father that she would like to go on the stage and promised that she would not make a fool of herself. James reluctantly gave in to the child’s request and allowed Annie to help her prepare Maude for her second stage appearance.

Maude was to play the part of the small boy, Little Schneider, in “Fritz.” She had nearly a hundred lines to speak in the play, but she memorized them in a couple of days. Critics hailed her first night as letter perfect. The theatre managers were so impressed with her talent they began to bill her on the program as “Little Maudie,” and it was by that name that she was known in the West throughout her career as a child actress.

By the age of seven “Little Maudie” was the reigning child actress of the Pacific Slope. David Belasco, known as the greatest American stage manager, became the child star’s manager. He was captivated by her talent and charm, and along with Annie would help shape Maude into the acting legacy she became.

Annie doted on her child and was immensely proud of her acting ability. When the parts were given out to the company, she was always letter perfect in Maudie’s lines long before she attempted to learn her own. Everywhere the mother and daughter team went they were practicing lines and Annie was helping her daughter understand the character she was to play on stage. They practiced in their dressing rooms, on the street cars and at their home. Maude had an exceptional memory and was a quick study. David was inspired by Annie’s attention to her daughter’s career and years later recalled how he could never see the child on stage without a picture rising up before him of her hardworking, self-sacrificing mother.

David Belasco’s management skills combined with Annie Adams’ tutelage helped make Maude Adams one of the most successful child stars in the West. Quick growth spurts made it impossible for Maude to continue playing children’s parts after a time. She turned 10 in 1882 and her mother decided Maude needed to semi-retire from the theatre and attend school. Annie enrolled her gifted daughter in the Presbyterian Collegiate Institute in Salt Lake City. For four years Maude studied drama and all matters of theatrical production. She was proficient at the harp and learned to speak French fluently. At the age of fourteen she had accomplished so much that she was within a year of graduating.

Maude missed her mother terribly during her years at the Institute. She missed her home and the stage as well. She wrote Annie begging her to let her return to her ‘old work.’ School was fine, but it wasn’t fulfilling to the actress.

Annie gave in to her daughter’s urgings. Maude left school and returned to her mother by the summer. The stage life she had left as a child was not the same when she returned. Her accomplishments as a child actress were merely a novelty now. She found herself a mere nonentity; to her professional friends she was merely “Annie Adams’ daughter.” Annie’s standing as an actress could do little more for her at first than to secure her some temporary engagements as an extra girl. Maude did not take lightly any role she was given, no matter how small. She studied, she watched, she learned many parts. She believed that someday she would be able to use all she had been taught by her mother and other members of the stock company.

Annie’s faith in her daughter’s future never wavered for an instant. She decided to take the teenager to New York, where theatrical parts were abundant. Annie believed Maude might be offered more challenging roles there. After auditioning for several shows, Maude landed a role in the play “The Paymaster.” She had developed into a captivating young girl and was now billed as Miss Maude Adams. David Belasco was in the audience the night the play opened. He had not seen Maude for seven years.

At the end of the run of Midnight Bell, Maude was a much talked- about actress. In all parts of town people were asking each other if ‘they had seen the new little girl in Hoyt’s play at the Bijou?’ Everyone agreed that she was sweet. Offers began pouring in for Maude to star in various productions around town. Charles Hoyt was willing to let her name her own terms if she would sign a five year contract with him. He knew he had struck gold with her talent. Maude declined Hoyt’s offer and signed with manager Charles Frohman. She had decided she wanted to focus on doing serious dramas and Frohman promised her the opportunity.

Frohman hired professional playwrights to create roles for Maude that would give her the chance to exercise her talent to the fullest. The first result was Nell, the lame girl, in a play called “The Lost Paradise.” It was a charming role that showed for the first time what Maude could do in the way of pathos. The favorable reviews led Charles to team the actress with the most popular actor of the day, John Drew. It was a stroke of management genius – one that would help launch Maude as one of the most popular American actresses in the world. Critics and audiences alike raved about her performance and flocked to the theatre to see her every chance they got.

John Drew and Maude Adams worked together in six different plays. Newspaper reviewers wrote that ‘she arrived on the other side of her teaming up with Drew as one of the most accomplished and womanly artists of all the younger actresses.’ It was at this point that Frohman decided the time was now ripe for Maude to come out as a star.

Charles Frohman set about searching for a vehicle that would secure his client’s position as a rising star in the theatre. He hired the well-known Scottish author J.M. Barrie (author of “Peter Pan”) to turn his popular novel “The Little Minister” into a play. Barrie delivered a powerful manuscript and both Frohman and Maude agreed it would make for a stellar debut. After a week of preliminary performances in Washington, Miss Adams made her first metropolitan appearance as a star at the Empire Theatre in New York on September 28, 1897. “The Little Minister” was a huge success, in which Maude Adams as an artist and J.M. Barrie as a playwright shared almost equally. New York critics praised her work.

That performance at the Empire began one of the most remarkable successes in theatrical history. Maude took her Lady Babbie role in “The Little Minister,” west in 1898. Sunday schools cried for her and clergymen of all denominations flocked to see the play.

From coast to coast of the United States the verdict of the playgoers seemed universal: there was only one thing greater than “The Little Minister,” and that was Maude Adams herself. Her popularity soared. Clever businessmen cashed in on that popularity naming the products they sold or manufactured, from children’s toys to corsets and cigars, after the star.

Maude was uneasy with the fame she had earned. She was pleased with the attention, but was fearful audiences would never accept her in any role other than Lady Babbie. She decided to study Shakespeare and by the end of the season she had mastered the role of Juliet. Frohman was galvanized by her dedication and drive and decided to hire a special company of actors and produce “Romeo and Juliet.” By May 1898, Maude’s interpretation of Juliet had been seen in all the leading cities across the country. She deviated from the traditional presentation of the character and decided to play Juliet as a simple, girlish creature of infinite charm. Her performance was recognized by the masses as being ‘the master-stroke of a very clever woman.’ Maude approached her career with a renewed sense of confidence, having proven to herself that audiences appreciated her talent regardless of the part she was playing.

Maude followed up her performance in “Romeo and Juliet” with lead roles in the plays “L’Aiglon,” “Quality Street” and “Joan of Arc.” In between shows she returned to Utah to visit her family. She spent a lot of time with her grandmother, finding great inspiration in their conversations and in the lovely valley of Salt Lake.

Very little is known about Maude’s personal life. She was intensely private and took great pride in the fact that there was scarcely a woman on stage the public knew less about. Historians record that she loved horses and was an exceptional rider. She owned a homestead and farm on Long Island and suffered a nervous breakdown from overwork in the early 1900s. It is rumored that she was deeply in love with her mentor and manager Charles Frohman, but as she drew the line very distinctly between her stage career and her private life, little can be substantiated with regards to an affair between the two.

In an interview done for a national magazine in 1894, Maude commented on her reasons for wanting to keep her personal life personal. “I don’t see why an actress must give her personality to the world, though it seems to be expected, and those who curiously investigate her personal life are not always careful how they use their information.”

In 1904 Maude starred as Peter Pan in one of the most enduring and beloved children’s plays ever written. J.M. Barrie adapted the part especially for her and conveyed in a letter to the actress that she inspired the character of the boy who refused to grow up.

Maude performed the leading role in “Peter Pan” in more than 1,500 performances. During the play’s run, she never left the theatre if children might be waiting outside because she didn’t want to spoil their illusion of the magical, flying boy by letting them see she was a woman. When she played the role in Salt Lake City, children from local orphanages were invited to a matinee. The director of St. Ann’s Orphanage later said that “The only trouble is that it has kept the entire corps of nurses busy trying to prevent the children from flying out the windows.”

Maude followed up her success as “Peter Pan” in starring roles in three more plays by Barrie: “The Pretty Sister of Jose,” “The Jesters” and “What Every Woman Knows.” Outside of the Metropolitan theatre in San Francisco, one of her favorite venues to perform in out west was the Hearst Greek Theatre of the University of California at Berkley. There she introduced audiences to a variety of intriguing characters created by playwright Edmond Ronstand. Audiences consistently hailed her performances as remarkable.

Maude’s accomplishments as a thespian were exceptional, but she excelled in the art of stage lighting as well. She had always been fascinated with the technical aspects of a show and long experience, research, a natural flair for the mechanics involved and a sense of color had given her an advantage. The gifted actor Lionel Barrymore remarked in his autobiography that Maude “could not resist supervising the lights for any given performance.” She felt proper lighting would give the actors on stage a better look and enhance their on-stage presence.

During her thirty plus years in the theatre, Maude spent considerable time in the development of stage illumination. She made so much progress in the study that many engineers looked upon her as an expert. With the help of a skilled electrician she created the widely used dimmer box, a main switch board that controls every light used in the production of the show, including the spotlights.

In 1921, Maude parlayed her love of stage lighting into a job working for General Electric Laboratories. There she experimented with color lamps for movies. She invented a high-powered incandescent lamp that eventually made colored movies possible. An electrical inventor at the lab filed a patent on the product, giving her no credit at all for her contribution. She was advised to sue but refused to pursue litigation and later noted in her diary that she thought herself an “idiot” for her decision.

In 1915, Maude was forced to deal with a series of devastating tragedies. Her mother, grandmother and her manager, Charles Frohman, all died within a short time of one another. The loss of Charles was particularly hard on the actress. Frohman was a passenger on the Lusitania, the passenger ship sunk by a German U-boat. Her grief over his death was a major factor in her decision to temporarily retire from acting. Being independently wealthy at this point in her career, she could afford to do so. She was persuaded to return to the stage only two more times before retiring altogether. Thirteen years after Charles’s death she portrayed the character Portia in the “Merchant of Venice” in Ohio. Her final stage performance was in 1934 at the theatre in Maine, playing Maria in “Twelfth Night.”

In 1937, Maude was invited to join the staff of Stephens, a girl’s junior college in Columbia, Missouri. She was the head of the drama department for six years. She retired from teaching in 1950. Three years later she was hospitalized with complications from pleurisy. So many cards and letters poured in that a large pillowcase was needed to hold them. Though she had been out of the public eye for twenty years, people had not forgotten her.

Maude Adams passed away on July 17, 1953 at her home in Tannerville, New York. She was eighty-one years old. She was buried in the private cemetery at the Cenacle Convent at Ronkonkoma, Long Island.

To learn more about Maude Adams and other famous entertainers on the frontier read Gilded Girls: Women Entertainers of the Old West.

Available everywhere books are sold.