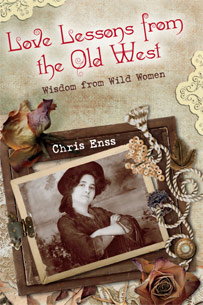

A woman can go further with a lipstick than a man can with a Winchester and a side of bacon. For more quips and other stories about love lessons learned by wild women of the west plan to read Love Lessons Learned from the Old West coming soon. Order your copy now through Amazon.com. Register to win a Love Lessons Learned gift package when you submit your own love lessons learned. The gift package includes a copy of Love Lessons Learned from the Old West: Wisdom from Wild Women, Love Lessons Learned coffee mugs, cocoa, soap, candles, day planners, pen, and a journal to keep track of every love lesson that comes your way. To enter Love Lessons Learned gift package giveaway visit www.chrisenss.com, click on Stay in Touch, and send a brief note about the love lessons you’ve learned. The best love lesson wins the gift package. A winner will be announced on February 14, 2014. Good luck!