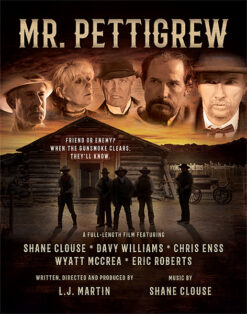

Enter now to win a copy of

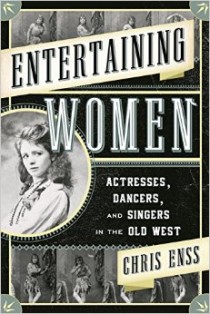

Entertaining Women: Actresses, Dancers, and Singers in the Old West

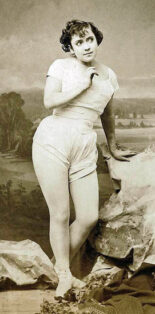

The angry hawk clenched its talons on the heavy leather gauntlet, stabbing the delicate wrist beneath. Wings batting, the half-wild bird glared fiercely into the large, gray eyes of his captor. Mary Anderson stared back with steely determination. This unruly bird would be tamed, she resolved, and would become a living prop for her performance of the Countess in Sheridan Knowles’ comedy, Love. A stuffed bird would not provide the realism she intended, and what Mary Anderson intended usually came to be.

“There is a fine hawking scene in one of the acts,” Mary wrote in her memoirs, “which would have been spoiled by a stuffed falcon, however beautifully hooded and gyved he might have been; for to speak such words as: ‘How nature fashion’d him for his bold trade, / Gave him his stars of eyes to range abroad, / His wings of glorious spread to mow the air, / And breast of might to use them’ to an inanimate bird, would have been absurd,” she declared. Always absolutely serious about her profession, Mary procured a half-wild bird and set to work on bending its spirit to her will.

“The training,” she explained, “started with taking the hawk from a cage and feeding it raw meat hoping thus to gain his affections.” She wore heavy gloves and goggles to protect her eyes. The hawk was not easily convinced of her motives, and “painful scratches and tears were the only result.”

She was advised to keep the bird from sleeping until its spirit broke, but she refused to take that course. Persevering with the original plan, Mary continued to feed and handle the hawk until it eventually learned to sit on her shoulder while she recited her lines, then fly to her wrist as she continued; then, at the signal from her hand, the bird would flap away as she concluded with a line about a glorious, dauntless bird.

The dauntless hawk and Mary Anderson were birds of a feather.

Entertaining Women 4

I'm looking forward to hearing from you! Please fill out this form and I will get in touch with you if you are the winner.

Join my email news list to enter the giveaway.

"*" indicates required fields

To learn more about Mary and other performers like her read

Entertaining Women: Actresses, Dancers, and Singers in the Old West