Railroad tycoon Lottie Devolle and her daughter Bernice thought they could get away with murder. They were wrong. Laura Reno is on the way.

Lola Montez was one of the more flamboyant figures of the gold rush days. She came to California by way of Ireland (where she was born), the music halls of London and Paris (where she danced), and the castle of Louis I Bavaria, which she had to vacate in ‘48 when the revolution drove Louis off the throne. The dark-haired beauty set herself up in royal style in Grass Valley, but the more conservative elements in the mining center rebelled against the soirees the ex-royal mistress ran. Lola, who was also a princess, courtesy of Louis, threatened to horsewhip an overcritical editor and then packed up and decided to try Australia. She spent her last days in New York saving the souls of lost women. It was a field she knew well. For more information about Lola Montez and other women of the California’s Gold Country read With Great Hope: Women of the California Gold Rush. Visit www.chrisenss.com.

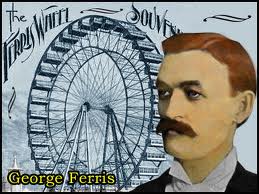

The second edition of Tales Behind the Tombstones isn’t scheduled to be released for a year, but I couldn’t resist sharing one of the tales now. The symbol of the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 was a giant 250-foot steel wheel, designed and erected under the supervision of George W. G. Ferris, Jr. It had 36 wooden seats that allowed 1,440 to ride at a time, taking them 25 stories above the fair at a then-exorbitant price of fifty cents apiece. The wheel was considered a wonder of technology and made Ferris, a former bridge inspector, a famous and a wealthy man during its heyday. But in 1896 he was worried about where future money would come from and, some believed because of his stress contracted typhoid fever. He died five days after its onset at age thirty-seven. Reports suggested that it was suicide, since his wife had left him three months before and he was apparently heartbroken and depressed. The wheel was moved and reassembled in New Orleans for the 1904 fair. However, two years later, what many felt was the American Eiffel Tower was dynamited, its rusted spokes buried in a landfill. Ferris’s name still stands on thousands of rides as a legacy-ironic that, since no one ever came to claim his cremated ashes.

Nellie Bly was one of the most rousing characters of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the 1880s, she pioneered the development of “detective” or “stunt” journalism, the acknowledged forerunner of full-scale investigative reporting. While she was still in her early twenties, the example of her fearless success helped open the profession to coming generations of women journalist clamoring to write hard news. Bly performed feats for the record books. She feigned insanity and engineered her own commitment to a mental asylum, then exposed its horrid conditions. She circled the globe faster than any living or fictional soul. She designed, manufactured, and marketed the first successful steel barrel produced in the United States. She owned and operated factories as a model of social welfare for her 1,500 employees. She was the first woman to report from the Eastern Front in World War I. She journeyed to Paris to argue the case of a defeated nation. She wrote a widely read advice column while devoting herself to the plight of the unfortunate, most notably unwed and indigent mothers and their offspring. Bly’s life – 1864 to 1922 – spanned Reconstruction, the Victorian and Progressive eras, the Great War and its aftermath. She grew up without privilege or higher education, knowing that her greatest asset was the force of her own will. Bly executed the extraordinary as a matter of routine. Even well into middle age, she saw herself as Miss Push-and-Get-There, the living example of what, in her time, was “That New American Girl.” To admirers, she was Will Indomitable, the Best Reporter in America, the Personification of Pluck. Amazing was the adjective that always came to mind. As the most famous woman journalist of her day, as an early woman industrialist, as a humanitarian, even as a beleaguered litigant, Bly kept the same formula for success: Determine Right. Decide Fast. Apply Energy Act with Conviction. Fight to the Finish. Accept the Consequences. Move on. Nelllie Bly is an example of possibility. She viewed every situation as an opportunity to make a significant difference in other people’s lives as well as her own. Not wealth or connections or position or beauty or outstanding intellect eased her way to greatness. She never dwelled on inadequacy or defeat. Bly just harnessed her pluck, her power to decide, and then did as she saw fit, to both impressive and disastrous ends.

It would be hard to find nicer people than those I met in Mariposa this past weekend. I was at the Chamber of Commerce/Visitor Center doing a book signing for the title High Country Women: Women Pioneers of Yosemite and I made the acquaintance of many Mariposa residents as well as Yosemite travelers. I had a chance to talk with a couple of park visitors and tell them all about the history of Yosemite. The two smiled and nodded pleasantly. It wasn’t until I’d been talking for seven or eight minutes that one of the smiling tourists informed me that they didn’t speak English. A number of campers came in to buy a book. Some let me know they were “rouging it just like the pioneers.” I can’t help but think that if pioneers knew people were sleeping outside in tents instead of in air conditioned hotels where Snickers candy bars and chocolate milk were down the hall in a vending machine, they would be scratching their heads in bewilderment. Camping was a necessity for pioneers. I’ve got to believe if a Hilton was anywhere near the Sierra foothills in 1846 the Donner Party would have checked in immediately. There’s a tremendous amount of pressure to love camp where I live in the Gold Country. I try to convince myself it might be fun, but ultimately I don’t like bugs and bugs seem to be a major component of camping. I guess camping and hiking just wasn’t coded into my DNA. Oh, I got out to enjoy the beautiful national park this weekend. I took some lovely photos of Yosemite from my vehicle. I drove to various scenic spots and marveled at the magnificence of God’s creation. Then I got back into my truck and drove to a hotel where I spent the night next door to the room where the couple who didn’t speak English were staying. I guess I just have to follow Oscar Wilde’s advice: Be yourself, because everyone else is taken.

I’ll be signing copies of the new book High Country Women: Pioneers of Yosemite National Park tomorrow from 1-4 p.m. at the Mariposa Chamber of Commerce. California Assemblywoman Kristin Olsen was going to attend, but something came up. She sent along a letter to share with visitors tomorrow. That was right nice of her. In addition to her note I thought I’d include a few facts about Yosemite. Enjoy. Ribbon Falls in Yosemite National Park is 9 times larger than Niagra Falls. El Capitan is the largest granite block in the world. There are 747,956 acres of land in Yosemite National Park Mountains at Yosemite National Park are still growing at a rate of 1 foot per 1,000 years 94% of the park is designated “wilderness”. In 1899, almost 100 years after the Park was established, there were only 4,500 visitors. Today, more than 4 million have visited the beauty that Yosemite National Park holds. And now a word from Assemblywoman Olsen. Dear Ms. Enss, Congratulations on the launch of your book High Country Women: Pioneers of Yosemite National Park. I’m sorry I wasn’t able to join you in person today, but I am honored to have had the opportunity to write the forward for your book and to be a part of your historic work. As we all know, California is an incredible place to live, and it’s because of its rich history and natural resources that so many people choose to call it home. Reading High Country Women took me back, not only to centuries ago when several inspiring and incredible women shaped the future of our state, but also to my childhood when I enjoyed visiting Yosemite and California’s Gold Country on a frequent basis with my family. You did an exceptional job of chronicling the many strong women whose lives were integral to the Yosemite we all know and love today. I thank you for the time and talent you invested in this book so that many others can take the same journey. All the best, Kristin Olsen Assemblywoman, 12th District.

I’m heading off this Saturday, August 17 to do a book signing at the Mariposa Chamber of Commerce for the new title High Country Women: Pioneer of Yosemite National Park. The Mariposa Chamber of Commerce is located at 5158 Cal 140 in Mariposa, California. The signing will take place from 1-4 p.m.. Stop by and visit if you’re in the area.

There was an art to organizing a great posse. There was more to it than just calling on a few buddies to bring their horses and guns and join in on a long ride to find the bad guys. The business of putting together a great posse fascinates me and that’s why I decided to write about the subject. A lot of what lawmen like Charles LaFlore and Bill Tilghman knew about forming a smart posse was common sense. Which oddly enough is not so common. The same ideas that were used to organize a posse can be applied in business. No one knew that better than detective Allen Pinkerton. The Pinkerton National Detective Agency, founded in the 1850s, is still in existence today. Wish I would have researched this topic before I invested all my cash in that Christmas present opening service.

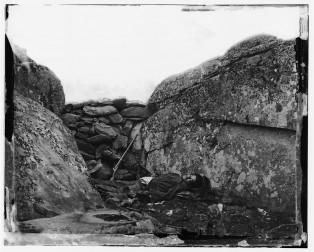

President Lincoln wrote this letter after an aide told him about a Boston widow whose five sons had been killed fighting for the Union armies. As Carl Sandburg wrote, “More darkly than the Gettysburg speech the letter wove its awful implication that human freedom so often was paid for with agony.” Here is an American president understanding that agony, sharing it, and performing a heartfelt rite, as Sandburg put it, “as though he might be a ship captain at midnight by lantern light, dropping black roses into the immemorial sea for mystic remembrance and consecration.” In a letter dated November 21, 1864, President Lincoln wrote the following to Mrs. Bixby in Boston, Massachusetts. “Dear Madam, I have been shown in the files of the War Department a statement of the Adjutant General of Massachusetts that you are the mother of five sons who have died gloriously on the field of battle. I feel how weak and fruitless must be any word of mine which should attempt to beguile you from the grief of a loss so overwhelming. But I cannot refrain from tendering you the consolation that may be found in the thanks of the republic they died to save. I pray that our Heavenly Father may assuage the anguish of your bereavement, and leave you only the cherished memory of the loved and lost, and the solemn pride that must be yours to have laid so costly a sacrifice upon the altar of freedom. Yours very sincerely and respectfully, A. Lincoln.” We now know that Lincoln had been misinformed: two of Mrs. Bixby’s sons had been killed in action, one was taken prisoner, and two deserted. The error does not stand in the way of the letter’s deserved fame. Mrs. Bixby’s loss and sacrifice hardly could have been greater. Lives are still being lost to save a nation.

It might seem as though the idea of exercising and eating right was a notion unheard of prior to the 21st century, but that’s not the case. According to the December 9, 1882 edition of the New York Medical Gazette, women physicians, however rare they were at the time, subscribed to the belief that a “healthy diet and a brisk turn about the neighborhood is good for the mind and body.” I personally don’t care how far back the idea of exercise and eating right extends. I hate to exercise or eat right. When I think about it, the only exercise program that has ever worked for me is occasionally getting up in the morning and jogging my memory to remind myself exactly how much I hate to exercise and to pick up another box of Cap’n Crunch next time I venture out of my office. Walking? Walking? If it’s so good for you, how come my mailman looks like Jabba the Hut with a quirky thyroid? But I digress. In the summer of 1882, a patient who wanted to lose weight visited Doctor Phyllis Groussin of Denver. Doctor Groussin put the 252 pound woman on a brown rice only diet and told her to march around her the neighborhood twice a day. After a week the dieter returned to the doctor complaining of “giddiness, headaches, difficulty in walking, and a want of accuracy in manual movements.” Fearing apoplexy, Doctor Groussin turned all her attention in that direction and prescribed purgatives, mustard footbaths and bicarbonate soda to dilute the blood. The doctor found out by accident that her patient was mixing the footbath water with whiskey and drinking it. The patient thought the concoction would help her in her efforts to “march around the neighborhood.” Now that’s a fitness goal. If you’re interested in learning more about women physicians of the Old West read The Doctor Wore Petticoats. Visit www.chrisenss.com for more information.