Forty-niners who trekked across the frontier during the Gold Rush often sang songs written by composer Stephen Foster as they traveled. Foster had a way with sentimental words and catchy melodies that has kept his songs popular for more than a century. There’s something pleasantly wholesome and irresistibly old-fashioned about songs like “Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair” and “Oh! Suzanna.” Two have been adopted by states, “My Old Kentucky Home” and Florida’s “Old Folks at Home” (“Swanee River”). What is ironic is that the composer of such unabashed sentimentality-born on the fiftieth birthday of the nation-ended up so miserably. Foster, who grew up singing but had very little musical training near Pittsburg, was successful almost from his first published songs in 1848. He earned more than $1,000 a year in royalties and married in 1850. But he always spent more than he made and the marriage was unhappy. He wrote fewer songs each year until he left his wife and daughter in 1860 and moved to New York City. There, desperate for cash, he churned out 105 songs-more than half of his entire work-in the last three and a half years of his life. Most were soon forgotten, and his previously lucrative publishing arrangement deteriorated to the point that Foster was selling songs outright for a quick $25. The composer, who drank heavily and suffered symptoms of tuberculosis, grew bitter and lonely as he lived in a series of rooming houses. On January 10, 1864, bedridden with fever, Foster got up to wash himself. Apparently as he stood over the washbasin he fell, shattering the porcelain bowl, which cut his neck deeply. He was found by a chambermaid delivering towels later that day. George Cooper, one of his few friends, was summoned to hear Foster whisper, “I’m done for,” and plead for a drink. Foster was taken to the city-run Bellevue Hospital, where he died, alone and unrecognized, three days later. The hospital, which had registered the 37-year-old composer as Stephen Forster, put his body in the morgue for unknown corpses until Cooper retrieved it. Unlike nearly all that he wrote in his final years, Foster’s last song, which he penned just a few days before he died, joined his earlier classics: Beautiful dreamer, wake unto me. Starlight and dew-drops are waiting for thee. Sounds of the rude world heard in the day, Lull’d by the moonlight have all pass’d away.

Journal Notes

American Gold Rush Part 1

Go West, Marx Brothers

This weekend let your troubles “Go West” with the Marx Brothers. Groucho, Chico and Harpo make even “Dead Man’s Gulch” come to life in this film released in 1940. The movie begins with Groucho attempting to fleece Chico and Harpo of the ten dollars he needs to make up the price of a railway ticket and being completely outsmarted. It’s hilarious. The movie contains a Keystone Cops-like chase in which the boys demolish a train in pursuit of the villains. Also funny. Go West features some of Groucho’s best lines. As he’s romancing a saloon girl he says, “Why don’t you let me go? But no, let’s keep this a perfect memory, and someday this bitter ache shall pass, my sweet. Time wounds all heals. You know, there’s a drunk sitting at the first table who looks exactly like you-and one who looks exactly like me. Dull, isn’t it? He’s so full of alcohol, if you put a lighted wick in his mouth, he’d burn for three days. So, let’s go somewhere where we can be alone. Ah, there doesn’t seem to be anyone on this couch.” This was one of the Marx Brothers last films and they only agreed to do Go West because Chico was in trouble. He gambled a lot and needed financial help. Go West helped him get out of debt, but in a short time he was back in the same situation and the brothers had to go to work again. There wasn’t anything the Marx Brothers wouldn’t do for one another.

This weekend let your troubles “Go West” with the Marx Brothers. Groucho, Chico and Harpo make even “Dead Man’s Gulch” come to life in this film released in 1940. The movie begins with Groucho attempting to fleece Chico and Harpo of the ten dollars he needs to make up the price of a railway ticket and being completely outsmarted. It’s hilarious. The movie contains a Keystone Cops-like chase in which the boys demolish a train in pursuit of the villains. Also funny. Go West features some of Groucho’s best lines. As he’s romancing a saloon girl he says, “Why don’t you let me go? But no, let’s keep this a perfect memory, and someday this bitter ache shall pass, my sweet. Time wounds all heals. You know, there’s a drunk sitting at the first table who looks exactly like you-and one who looks exactly like me. Dull, isn’t it? He’s so full of alcohol, if you put a lighted wick in his mouth, he’d burn for three days. So, let’s go somewhere where we can be alone. Ah, there doesn’t seem to be anyone on this couch.” This was one of the Marx Brothers last films and they only agreed to do Go West because Chico was in trouble. He gambled a lot and needed financial help. Go West helped him get out of debt, but in a short time he was back in the same situation and the brothers had to go to work again. There wasn’t anything the Marx Brothers wouldn’t do for one another.

Arizona

There’s nothing more satisfying for me than watching a great western. More often than not criminals in a good western do not die by the hands of the law. They die by the hands of other men. The men they wronged. The outlaws in a great many westerns I watch know they won’t get away. They know they ultimately can’t get away. I once knew a man who committed no crime, but was sentenced to prison because he was persuaded to take a plea. He’d been severely beaten and raped at a penitentiary transfer station. So they put him in a hospital to make him better so that they could make him worse. He was destined to be beaten and raped again. During the eight years he was gone, he collapsed a number of times as a result of Parkinson’s disease, and the doctors put him in the hospital again. He became friends with the nurses and the doctors, and after a while they helped him to get well enough to go back and take more punishment. I saw him after the brutal attacks and he was a broken man. The spirit of the man was gone. The person sitting next to me during the visit with the man said, “This country’s law and their stinking judges! Isn’t anyone going to do something about them?” Staring into the hollow face of the beaten man I once knew as my brother I said, “I don’t want the people who made the law, and I don’t want the people who passed the sentence. The only ones I want to see get theirs are those that falsely accused and caused this pain.” I am convinced that will never really happen. A good western soothes my soul in the midst of the conflict raging in my mind. Last night I enjoyed watching Arizona. Released in 1940, Arizona is more memorable for the thousands of feet of stock footage it provided for other films. For this tale of the development of Arizona, Columbia reconstructed Tucson as the mud-adobe town it had been while the movie’s director, Wesley Ruggles, created set-pieces in the style of De Mille. In one of the movie’s best scenes, the town’s inhabitants watch the Union troops setting light to everything in their wake, as they withdraw. Gary Cooper and Jean Arthur starred in the picture.

There’s nothing more satisfying for me than watching a great western. More often than not criminals in a good western do not die by the hands of the law. They die by the hands of other men. The men they wronged. The outlaws in a great many westerns I watch know they won’t get away. They know they ultimately can’t get away. I once knew a man who committed no crime, but was sentenced to prison because he was persuaded to take a plea. He’d been severely beaten and raped at a penitentiary transfer station. So they put him in a hospital to make him better so that they could make him worse. He was destined to be beaten and raped again. During the eight years he was gone, he collapsed a number of times as a result of Parkinson’s disease, and the doctors put him in the hospital again. He became friends with the nurses and the doctors, and after a while they helped him to get well enough to go back and take more punishment. I saw him after the brutal attacks and he was a broken man. The spirit of the man was gone. The person sitting next to me during the visit with the man said, “This country’s law and their stinking judges! Isn’t anyone going to do something about them?” Staring into the hollow face of the beaten man I once knew as my brother I said, “I don’t want the people who made the law, and I don’t want the people who passed the sentence. The only ones I want to see get theirs are those that falsely accused and caused this pain.” I am convinced that will never really happen. A good western soothes my soul in the midst of the conflict raging in my mind. Last night I enjoyed watching Arizona. Released in 1940, Arizona is more memorable for the thousands of feet of stock footage it provided for other films. For this tale of the development of Arizona, Columbia reconstructed Tucson as the mud-adobe town it had been while the movie’s director, Wesley Ruggles, created set-pieces in the style of De Mille. In one of the movie’s best scenes, the town’s inhabitants watch the Union troops setting light to everything in their wake, as they withdraw. Gary Cooper and Jean Arthur starred in the picture.

Gambling

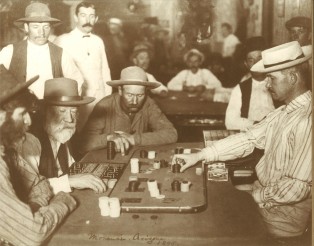

American’s oldest diversion deteriorated into a vice. In the turn of a card or the roll of a dice for all or nothing, there was a kind of daring that touched the American spirit. “The lust for work is matched…by the lust to gamble.” The affluent risked thousands of comforts; the poor risked bread money on gaming tables in slum taverns. The gambling fever produced two opposing species. First were the predatory card sharps and confidence men who understood human weakness and how to exploit it; second were the masses, eternally gullible to the lure of something for nothing. Throughout the nation these adversaries met-in lotteries, over tables, at racetracks, in casinos, cockpits-and the result was nearly always the same. The suckers lost. In 1890, San Francisco had an estimated 2500 illegal gambling houses, which produced, as they did elsewhere, crime and degeneracy. And while these are hardly the by-products one would expect of a leisure activity, it should be remembered that vice can become a pastime for people who had little alternative resource. Starting with the Gold Rush era, the West from the Rio Grande to Canadian border knew no way to spend free hours except gambling. Judge or laborer, clergyman or clerk, all elbowed their way into the gambling tents.

American’s oldest diversion deteriorated into a vice. In the turn of a card or the roll of a dice for all or nothing, there was a kind of daring that touched the American spirit. “The lust for work is matched…by the lust to gamble.” The affluent risked thousands of comforts; the poor risked bread money on gaming tables in slum taverns. The gambling fever produced two opposing species. First were the predatory card sharps and confidence men who understood human weakness and how to exploit it; second were the masses, eternally gullible to the lure of something for nothing. Throughout the nation these adversaries met-in lotteries, over tables, at racetracks, in casinos, cockpits-and the result was nearly always the same. The suckers lost. In 1890, San Francisco had an estimated 2500 illegal gambling houses, which produced, as they did elsewhere, crime and degeneracy. And while these are hardly the by-products one would expect of a leisure activity, it should be remembered that vice can become a pastime for people who had little alternative resource. Starting with the Gold Rush era, the West from the Rio Grande to Canadian border knew no way to spend free hours except gambling. Judge or laborer, clergyman or clerk, all elbowed their way into the gambling tents.

The Lawman & the Six-Shooter

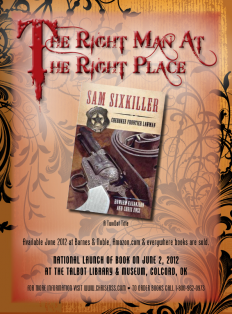

Old West partners to reckon with…Cherokee Lawman Sam Sixkiller and a six-shooter. Besides being a US deputy marshal, Sixkiller was a detective for the Missouri Pacific Railroad and in 1880 became the first captain of the US Indian Police (USIP), which was headquartered at Muskogee, Creek Nation. The USIP served under the Indian agent for the Five Civilized Tribes. Sam Sixkiller came out of this milieu of politics, crime, and upheaval and brought a sense of justice and fairness to the people who lived in the Cherokee Nation and the Indian Territory. Sixkiller became widely known and praised for his law enforcement skills, commitment, and understanding of duty to the job. The Oklahoma Historical Society plans to present its Outstanding Book on Oklahoma History (published in 2012) to Globe Pequot Press and Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss, publisher and authors of Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman during our Annual Awards Luncheon on April 19, 2013. For more information about the book Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman visit www.chrisenss.com.

Old West partners to reckon with…Cherokee Lawman Sam Sixkiller and a six-shooter. Besides being a US deputy marshal, Sixkiller was a detective for the Missouri Pacific Railroad and in 1880 became the first captain of the US Indian Police (USIP), which was headquartered at Muskogee, Creek Nation. The USIP served under the Indian agent for the Five Civilized Tribes. Sam Sixkiller came out of this milieu of politics, crime, and upheaval and brought a sense of justice and fairness to the people who lived in the Cherokee Nation and the Indian Territory. Sixkiller became widely known and praised for his law enforcement skills, commitment, and understanding of duty to the job. The Oklahoma Historical Society plans to present its Outstanding Book on Oklahoma History (published in 2012) to Globe Pequot Press and Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss, publisher and authors of Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman during our Annual Awards Luncheon on April 19, 2013. For more information about the book Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman visit www.chrisenss.com.

The Adventures of Deadwood Dick

Another great Old West partnership -Nat Love and roping. Nat Love (1854-1921) was born to slave parents on the Robert Love plantation in Davidson County, Tennessee. He was freed at the end of the Civil War, just after he turned eleven. At fifteen, he found a task he enjoyed, taming colts for a dime a head. Fortune smiled with a $100 raffle win, giving him enough bucks to split the winnings with his mother and head west. Outside Dodge City, after a wild audition on the back of a foul-tempered bronco called Good Eye, Love found work with the Duval cattle outfit from Texas. For three years, he was based in the Texas panhandle near the Palo Dura River. In 1872, he was in Arizona’s Gila River country working for Pete Gallinger as the resident authority on reading brands. In 1876, Love’s outfit received an order for 2,000 longhorns to be delivered to Deadwood in Dakota Territory. In Deadwood on the 4th of July, Love won a mustang roping contest and a shooting match. In addition to the prize money, the excited residents bestowed upon him the title of Deadwood Dick. In a time when men were known by their buckskin nicknames – Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill, Texas Jack – Love saw his dubbing as a badge of honor. Back in the Southwest, his party was attacked by warriors. Wounded in the leg, he passed out, only to awake in the camp of Yellow Dog. According to Love, he was told he was “too brave to die” and plans were made to adopt him. His ears were pierced with a bone from a deer’s leg. He was designated to marry Buffalo Papoose, daughter of the chief. A month later, with the wedding fast approaching, Love stole a pony and skipped out of camp. Twelve hours and one hundred miles later, he was back at the ranch. Meanwhile, in wild and woolly New York, author Edward Lytton Wheeler was finishing up a story for dime novel publisher Beadle and Adams. Wheeler had never been west of Pennsylvania, but on October 15, 1877, Deadwood Dick, the Prince of the Road; or the Black Rider of the Black Hills was published. Over the next eight years, Wheeler penned thirty-three Deadwood Dick novels, as well as a play, Deadwood Dick, A Road Agent, A Drama of the Gold Mines. The stories were so popular that faux Deadwood Dicks began crawling out of the woodwork. For more information about Beadle and Adams Dime Novels read The Raftsman’s Daughter by yours truly.

Another great Old West partnership -Nat Love and roping. Nat Love (1854-1921) was born to slave parents on the Robert Love plantation in Davidson County, Tennessee. He was freed at the end of the Civil War, just after he turned eleven. At fifteen, he found a task he enjoyed, taming colts for a dime a head. Fortune smiled with a $100 raffle win, giving him enough bucks to split the winnings with his mother and head west. Outside Dodge City, after a wild audition on the back of a foul-tempered bronco called Good Eye, Love found work with the Duval cattle outfit from Texas. For three years, he was based in the Texas panhandle near the Palo Dura River. In 1872, he was in Arizona’s Gila River country working for Pete Gallinger as the resident authority on reading brands. In 1876, Love’s outfit received an order for 2,000 longhorns to be delivered to Deadwood in Dakota Territory. In Deadwood on the 4th of July, Love won a mustang roping contest and a shooting match. In addition to the prize money, the excited residents bestowed upon him the title of Deadwood Dick. In a time when men were known by their buckskin nicknames – Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill, Texas Jack – Love saw his dubbing as a badge of honor. Back in the Southwest, his party was attacked by warriors. Wounded in the leg, he passed out, only to awake in the camp of Yellow Dog. According to Love, he was told he was “too brave to die” and plans were made to adopt him. His ears were pierced with a bone from a deer’s leg. He was designated to marry Buffalo Papoose, daughter of the chief. A month later, with the wedding fast approaching, Love stole a pony and skipped out of camp. Twelve hours and one hundred miles later, he was back at the ranch. Meanwhile, in wild and woolly New York, author Edward Lytton Wheeler was finishing up a story for dime novel publisher Beadle and Adams. Wheeler had never been west of Pennsylvania, but on October 15, 1877, Deadwood Dick, the Prince of the Road; or the Black Rider of the Black Hills was published. Over the next eight years, Wheeler penned thirty-three Deadwood Dick novels, as well as a play, Deadwood Dick, A Road Agent, A Drama of the Gold Mines. The stories were so popular that faux Deadwood Dicks began crawling out of the woodwork. For more information about Beadle and Adams Dime Novels read The Raftsman’s Daughter by yours truly.

Missie & Jimmy

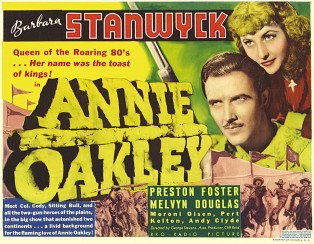

Among my favorite Old West partnerships is that of Annie Oakley and Frank Butler. The two met on Thanksgiving Day in 1875 in Oakley, Ohio and promptly squared off at a shooting competition. Annie was fifteen years old and stood just under five feet tall. Frank was twenty-three years old and was more than six feet tall. Annie won the shooting contest. Known to each other as Missie and Jimmy, the two married on June 22, 1876. Frank was impressed with Annie’s shooting skills and in 1882 began choreographing the trick shot and horseback riding routines she performed in the traveling circuses in which they were a part. The two had an impressive career together, appearing in venues all over the United States and Europe. They were married for more than fifty years when Annie died of pneumonia. Heartbroken, Frank stopped eating and died seventeen days after his wife. In 1935, the first western about Annie Oakley’s life starring Barbara Stanwyck opened in theatres across America. Annie Oakley, was an efficient, if historically inaccurate, biopic. Stanwyck plays the tomboy sharpshooter who romances fellow sharp shooter Preston Foster who portrays Frank Butler. The ninety minute film was directed by George Stevens. Stevens went on to make one of the definitive films in the genre – Shane. For more information about Annie Oakley and Frank Butler read Love Untamed: Romances of the Old West.

Among my favorite Old West partnerships is that of Annie Oakley and Frank Butler. The two met on Thanksgiving Day in 1875 in Oakley, Ohio and promptly squared off at a shooting competition. Annie was fifteen years old and stood just under five feet tall. Frank was twenty-three years old and was more than six feet tall. Annie won the shooting contest. Known to each other as Missie and Jimmy, the two married on June 22, 1876. Frank was impressed with Annie’s shooting skills and in 1882 began choreographing the trick shot and horseback riding routines she performed in the traveling circuses in which they were a part. The two had an impressive career together, appearing in venues all over the United States and Europe. They were married for more than fifty years when Annie died of pneumonia. Heartbroken, Frank stopped eating and died seventeen days after his wife. In 1935, the first western about Annie Oakley’s life starring Barbara Stanwyck opened in theatres across America. Annie Oakley, was an efficient, if historically inaccurate, biopic. Stanwyck plays the tomboy sharpshooter who romances fellow sharp shooter Preston Foster who portrays Frank Butler. The ninety minute film was directed by George Stevens. Stevens went on to make one of the definitive films in the genre – Shane. For more information about Annie Oakley and Frank Butler read Love Untamed: Romances of the Old West.

Lack of…

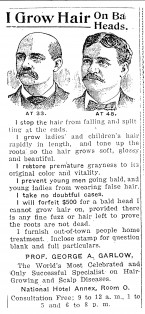

Miracle cures for hair loss were sold by snake-oil salesmen in the Old West and they are sold on the World Wide Web today. A “cure for baldness” has long been a profitable claim for nostrums. The Old West snake-oil salesman might sell his product as a cure for baldness when his audience was made up mostly of men, and a cure for “women’s complaints” when his audience was mostly women. In the next town, he might sell it as a cure for rheumatism. The common thread in all of his claims is they are unverified by any scientifically acceptable evidence. We might believe that we are more sophisticated and knowledgeable than the citizens of a small town in the Old West who gathered around the wagon of the snake-oil salesman to hear his pitch. While it is true that we are probably more knowledgeable because there is more information to know about, it is also true that the purveyors of nostrums incorporate today’s advanced knowledge into their claims. The Nineteenth Century snake-oil salesman might base his claims on “secret knowledge” passed along to him by an ancient medicine man. The purveyor of nostrums today is more likely to use words taken out of context from the sciences of genetics and biochemistry to link his claims to scientific research. Buyers beware!

Miracle cures for hair loss were sold by snake-oil salesmen in the Old West and they are sold on the World Wide Web today. A “cure for baldness” has long been a profitable claim for nostrums. The Old West snake-oil salesman might sell his product as a cure for baldness when his audience was made up mostly of men, and a cure for “women’s complaints” when his audience was mostly women. In the next town, he might sell it as a cure for rheumatism. The common thread in all of his claims is they are unverified by any scientifically acceptable evidence. We might believe that we are more sophisticated and knowledgeable than the citizens of a small town in the Old West who gathered around the wagon of the snake-oil salesman to hear his pitch. While it is true that we are probably more knowledgeable because there is more information to know about, it is also true that the purveyors of nostrums incorporate today’s advanced knowledge into their claims. The Nineteenth Century snake-oil salesman might base his claims on “secret knowledge” passed along to him by an ancient medicine man. The purveyor of nostrums today is more likely to use words taken out of context from the sciences of genetics and biochemistry to link his claims to scientific research. Buyers beware!

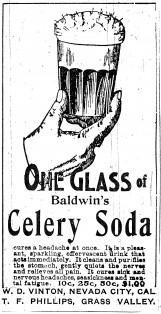

In Good Health

In the early 19th century most Americans healed themselves, as their ancestors had for centuries. Professional medical assistance was either too far away, too expensive, or both. Even wealthy urban families usually attempted some sort of home health care before the doctor was called. This care was usually administered with the aid of books, pamphlets, and proprietary medicines purchased at the general store. Proprietary medicine advertisements were the mainstay of newspapers in the Old West. Newspapers carried notices for medicated vapor baths, artificial teeth, genuine Galvanic Rings, the Anodyne Necklace and other amulets. Some patent medicine companies spent more than $100,000 a year advertising their products. Patent medicines were the hottest-selling items on store shelves. If the labels on the medicines were to be believed, they could handle just about any and every complaint. One concoction grandly promised to cure 30 different disorders, including “nervous debility caused by the indiscretions of youth.” Mostly they relied on heavy lacing alcohol to work their proclaimed wonders. It didn’t really cure what was ailing you but you didn’t mind so much.

In the early 19th century most Americans healed themselves, as their ancestors had for centuries. Professional medical assistance was either too far away, too expensive, or both. Even wealthy urban families usually attempted some sort of home health care before the doctor was called. This care was usually administered with the aid of books, pamphlets, and proprietary medicines purchased at the general store. Proprietary medicine advertisements were the mainstay of newspapers in the Old West. Newspapers carried notices for medicated vapor baths, artificial teeth, genuine Galvanic Rings, the Anodyne Necklace and other amulets. Some patent medicine companies spent more than $100,000 a year advertising their products. Patent medicines were the hottest-selling items on store shelves. If the labels on the medicines were to be believed, they could handle just about any and every complaint. One concoction grandly promised to cure 30 different disorders, including “nervous debility caused by the indiscretions of youth.” Mostly they relied on heavy lacing alcohol to work their proclaimed wonders. It didn’t really cure what was ailing you but you didn’t mind so much.