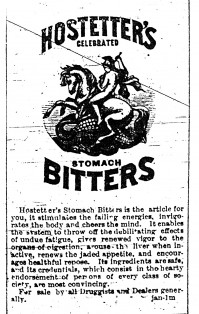

I’ll be speaking at the Nevada County Historical Society meeting tomorrow evening at 6:30 p.m. at the Madelyn Helling Library in Nevada City. The talk will center on the most recent book released The Bedside Book of Bad Girls: Outlaw Women of the Midwest. Email me for more information – gvcenss@aol.com. Hope to see you there. And now for this commercial message…. The stagecoach figured prominently in the early west. Under ideal condition, a coach driven by a fresh team of horses could “cut dirt” at the breakneck pace of nine miles per hour. Yet driving condition throughout much of the century were rarely ideal. Vehicles got stuck in ruts of mud so often that the expression “up to the hub” became a national colloquialism to illustrate any intractable predicament. Bad roads and driver impatience frequently combined to turn a coach over. During any long stage trip, in fact, passengers expected and were mentally prepared for at least one turnover.

I’ll be speaking at the Nevada County Historical Society meeting tomorrow evening at 6:30 p.m. at the Madelyn Helling Library in Nevada City. The talk will center on the most recent book released The Bedside Book of Bad Girls: Outlaw Women of the Midwest. Email me for more information – gvcenss@aol.com. Hope to see you there. And now for this commercial message…. The stagecoach figured prominently in the early west. Under ideal condition, a coach driven by a fresh team of horses could “cut dirt” at the breakneck pace of nine miles per hour. Yet driving condition throughout much of the century were rarely ideal. Vehicles got stuck in ruts of mud so often that the expression “up to the hub” became a national colloquialism to illustrate any intractable predicament. Bad roads and driver impatience frequently combined to turn a coach over. During any long stage trip, in fact, passengers expected and were mentally prepared for at least one turnover.

Journal Notes

More About Old West Ads

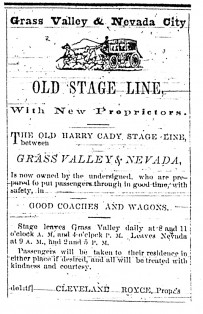

For those who might be feeling as poorly as a centipede with sciatic rheumatism the following Old West advertisement might just be the thing to make it better. In the early 19th century most Americans healed themselves as their ancestors had for centuries. Professional medical assistance was either too far away, to expensive, or both. Even wealthy urban families usually attempted some sort of home health care before the doctor was called. This care was usually administered with the aid of books, pamphlets, and proprietary medicines purchased at the general store. Proprietary medicine advertisements were the mainstay of newspapers in the Old West. Newspapers carried notices for medicated vapor baths, artificial teeth, genuine Galvanic Rings, the Anodyne Necklace and other amulets. Some patent medicine companies spent more than $100,000 a year advertising their products. Patent medicines were the hottest-selling items on store shelves. If the labels on the medicines were to be believed, they could handle just about any and ever complaint. One concoction grandly promised to cure thirty different disorders including “nervous debility caused by the indiscretions of youth.” Mostly they relied on a heavy lacing of alcohol to work their proclaimed wonders. Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters, for instance, soothed indigestion with a formula packing a fifty-proof wallop.

For those who might be feeling as poorly as a centipede with sciatic rheumatism the following Old West advertisement might just be the thing to make it better. In the early 19th century most Americans healed themselves as their ancestors had for centuries. Professional medical assistance was either too far away, to expensive, or both. Even wealthy urban families usually attempted some sort of home health care before the doctor was called. This care was usually administered with the aid of books, pamphlets, and proprietary medicines purchased at the general store. Proprietary medicine advertisements were the mainstay of newspapers in the Old West. Newspapers carried notices for medicated vapor baths, artificial teeth, genuine Galvanic Rings, the Anodyne Necklace and other amulets. Some patent medicine companies spent more than $100,000 a year advertising their products. Patent medicines were the hottest-selling items on store shelves. If the labels on the medicines were to be believed, they could handle just about any and ever complaint. One concoction grandly promised to cure thirty different disorders including “nervous debility caused by the indiscretions of youth.” Mostly they relied on a heavy lacing of alcohol to work their proclaimed wonders. Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters, for instance, soothed indigestion with a formula packing a fifty-proof wallop.

Absolutely Pure

Around the House

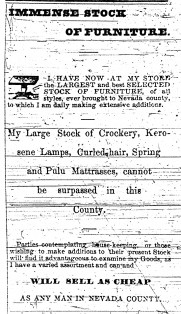

A one-room log cabin with dirt or puncheon floor, simple fireplace, sawbuck table and straw mattress in which an entire family might sleep – that was as far as luxury went on the frontier and in newly settled regions of the country. Long-settled communities enjoyed roomier abodes, of course, and as the wealth of the region and of the nation grew, houses became larger, more elaborate and better equipped. Specialized stores helped homeowners furnish their dwellings with the most fashionable sofas, chairs, and love-seats available. Early Victorian furniture was popular and the most common style carried by furniture stores. Victorian furniture was large and made of mahogany, rosewood or black walnut. Notable characteristics were saber legs; marble table tops; turned bedposts; mushroom-turned wooden knobs for handles; ornamentation in the form of carved medallions featuring flowers, fruits and foliage. There’s nothing simple about that look. I’m not surprised the advertisment boasted that the items were cheap.

A one-room log cabin with dirt or puncheon floor, simple fireplace, sawbuck table and straw mattress in which an entire family might sleep – that was as far as luxury went on the frontier and in newly settled regions of the country. Long-settled communities enjoyed roomier abodes, of course, and as the wealth of the region and of the nation grew, houses became larger, more elaborate and better equipped. Specialized stores helped homeowners furnish their dwellings with the most fashionable sofas, chairs, and love-seats available. Early Victorian furniture was popular and the most common style carried by furniture stores. Victorian furniture was large and made of mahogany, rosewood or black walnut. Notable characteristics were saber legs; marble table tops; turned bedposts; mushroom-turned wooden knobs for handles; ornamentation in the form of carved medallions featuring flowers, fruits and foliage. There’s nothing simple about that look. I’m not surprised the advertisment boasted that the items were cheap.

Old West Advertisement

The Passing of Harry Carey, Jr.

Boot Hill

Usually, a bad man was buried unceremoniously in a local “boot hill,” so called because most of those who were buried therein died with their boots on, and were even buried with them on. However, some had funerals; and tombstones with epitaphs marked their graves for some time, usually until souvenir hunters demolished them. On Sam Bass’ tombstone was engraved, “A brave man reposes in death here. Why was he not true?” On Seaborne Barnes’ gravestone was written, “He was right bower (meaning he was an anchor) to Sam Bass.” Besides his name and dates, Cole Younger’s tombstone had the words, “Rest in Peace, Our Dear Beloved.” Perhaps Jesse James’s complete epitaph should be given: “In Loving Remembrance of My Beloved Son, Jesse W. James, Died April 3, 1882, Aged 36 Years, 6 Months, 28 Days Murdered by a Traitor and Coward Whose Name is Not Worthy to Appear Here.” (I think I’ll have something like that inscribed on my brother’s tombstone.) The coward referred to was Bob Ford who, as you recall, shot Jesse in the back while he was hanging a picture on the wall, very unusually unarmed. Other than biographical information, Langford Peel’s tombstone bore the inscriptions: “In Life, Beloved by his Friends, and Respected by his Enemies. Vengeance is Mine, Saith the Lord, I Know That My Redeemer Liveth. Erected by a Friend.” Most unusual of the epitaphs of bad men was that of Lame Johnny, a man who never knew when to keep his mouth shut, hanged by impromptu vigilantes and award the epitaph: “Lame Johnny, Stranger, pass gently o’er this sod. If he opens his mouth, you’re gone, by God.”

Usually, a bad man was buried unceremoniously in a local “boot hill,” so called because most of those who were buried therein died with their boots on, and were even buried with them on. However, some had funerals; and tombstones with epitaphs marked their graves for some time, usually until souvenir hunters demolished them. On Sam Bass’ tombstone was engraved, “A brave man reposes in death here. Why was he not true?” On Seaborne Barnes’ gravestone was written, “He was right bower (meaning he was an anchor) to Sam Bass.” Besides his name and dates, Cole Younger’s tombstone had the words, “Rest in Peace, Our Dear Beloved.” Perhaps Jesse James’s complete epitaph should be given: “In Loving Remembrance of My Beloved Son, Jesse W. James, Died April 3, 1882, Aged 36 Years, 6 Months, 28 Days Murdered by a Traitor and Coward Whose Name is Not Worthy to Appear Here.” (I think I’ll have something like that inscribed on my brother’s tombstone.) The coward referred to was Bob Ford who, as you recall, shot Jesse in the back while he was hanging a picture on the wall, very unusually unarmed. Other than biographical information, Langford Peel’s tombstone bore the inscriptions: “In Life, Beloved by his Friends, and Respected by his Enemies. Vengeance is Mine, Saith the Lord, I Know That My Redeemer Liveth. Erected by a Friend.” Most unusual of the epitaphs of bad men was that of Lame Johnny, a man who never knew when to keep his mouth shut, hanged by impromptu vigilantes and award the epitaph: “Lame Johnny, Stranger, pass gently o’er this sod. If he opens his mouth, you’re gone, by God.”

Singing Cowboys

Old West cowboys looking for a job driving cattle across the plains were generally asked the following question. “Can you ride a pitching bronc? Can you rope a horse out of the remuda without throwing the loop around your own head? Are you good-natured? In the case of a stampede at night, would you drift along in front or circle the cattle to a mill? Just one more question: can you sing? Some cowboys could not. Every time they went on guard and sang, the cattle would get up and mill around the bed ground. Good cowboy singers would have to be called in to serenade the animals. The cattle would quickly lie down when they sang. Considering that so few cowboys could sing and that it wasn’t the quality of the singing that counted-just the reassuring sound of a familiar voice or even a humming or whistling or yodeling-it’s a wonder that cowboy songs are as good as they are. As a matter of fact, most cowboy songs, especially cowboy ballads, were written by known (if forgotten) cowboy poets, to older tuners. Except as they help to soothe restless cattle or to keep them moving, cowboy songs are not true work songs like sailor’s chanteys. They are more like lumberjack songs-occupational and recreational songs-in which men sing about their work and play and express certain occupational attitude. Cowboy songs have the freedom, casualness and uncomplicated quality of cowboy’s life. Because the cowboy’s subjects are so few and basic, he has mastered them and can handle them simply and sincerely. As the Chisholm Trail from Texas to Kansas was the classic cattle trail, so the song that takes its name from the trail is the classic trail song. The easy swing of the tune is deceptive considering the cowboy’s troubles on the trail-weather, food, boss, pay. Here are a few verses from the song The Old Chisholm Trail. “I wake in the mornin’ afore daylight and afore I sleep the moon shines bright. Oh it’s bacon and beans most every day; I’d as soon be a-eatin prairie hay. With my knees in the saddle and my seat in the sky, I’ll quit punchin’ cows in the sweet by and by.” I bet Roy Rogers could have lulled a herd of cattle into a coma with his voice. Ride on, Roy.

A Cowboys Neckerchief

A useful part of the cowboy’s costume was his neckerchief, or “wipes” as he called it. Neckerchiefs were usually red or blue, like the old bandana of the South, or black silk which did not show the dirt. The rodeo rider of modern days goes in for bright colors. Rangemen usually wished to avoid colors which attracted attention. An inconspicuous rider was more apt to catch a rustler. Usually the cowboy wore his neck scarf draped loosely over his chest with the knot in the back. If the sun shone on his back he reversed the scarf to protect his neck. When riding in the drag of a herd he pulled it up over mouth and nose to keep out the dust. In winter he might put it over his eyes to prevent snow blindness or to protect his face from icy winds and stinging sleet. He could use it to tie down his hat, to serve as an ear muff in cold weather, or to keep his head cool on a blazing summer day by wearing it, wet, under his hat. When he washed his face in the morning, an ever ready towel was hanging from his neck. In his work he had this handy mop to wipe the sweat off his face. He could use it for holding the handle of a hot branding iron, for a blindfold on a snaky horse, or as a “pigging string,” that is, a string for tying a roped animal by all four feet the way a hog is tied. Likewise the neckerchief could be used as a makeshift hobble for his horse, a tourniquet a sling for a broken arm, or a bandage. In the movie Appaloosa with Ed Harris and Vigo Mortensen, Mortensen’s character demonstrates just how important the neckerchief was to cowboys. In one scene he is carefully mending a tear in the garment. In addition to all these great uses I’ve found that the neckerchief is perfect for covering unsightly turkey neck.

A useful part of the cowboy’s costume was his neckerchief, or “wipes” as he called it. Neckerchiefs were usually red or blue, like the old bandana of the South, or black silk which did not show the dirt. The rodeo rider of modern days goes in for bright colors. Rangemen usually wished to avoid colors which attracted attention. An inconspicuous rider was more apt to catch a rustler. Usually the cowboy wore his neck scarf draped loosely over his chest with the knot in the back. If the sun shone on his back he reversed the scarf to protect his neck. When riding in the drag of a herd he pulled it up over mouth and nose to keep out the dust. In winter he might put it over his eyes to prevent snow blindness or to protect his face from icy winds and stinging sleet. He could use it to tie down his hat, to serve as an ear muff in cold weather, or to keep his head cool on a blazing summer day by wearing it, wet, under his hat. When he washed his face in the morning, an ever ready towel was hanging from his neck. In his work he had this handy mop to wipe the sweat off his face. He could use it for holding the handle of a hot branding iron, for a blindfold on a snaky horse, or as a “pigging string,” that is, a string for tying a roped animal by all four feet the way a hog is tied. Likewise the neckerchief could be used as a makeshift hobble for his horse, a tourniquet a sling for a broken arm, or a bandage. In the movie Appaloosa with Ed Harris and Vigo Mortensen, Mortensen’s character demonstrates just how important the neckerchief was to cowboys. In one scene he is carefully mending a tear in the garment. In addition to all these great uses I’ve found that the neckerchief is perfect for covering unsightly turkey neck.

Marshal Tom Smith

Several Kansas cow towns produced the West’s best known frontier marshals. Of these by far the most courageous was the one who had the shortest career. Thomas James Smith, the marshal of Abilene during its boom days as the original terminus of the Chisholm Trail. Tom Smith, more than any other, exemplified western fiction writer William MacLeod Raine’s (Raine is one of my favorite authors) description of frontier peace officers: “They usually were quiet men. They served fearlessly and with inadequate reward. Their resort to the six-shooter was always in reluctant self-defense. Early in the cattle season of 1870, Abilene had tried several marshals, but no one had lasted more than a few weeks. Finally, on June 4, the town trustees hired Tom Smith, a husky Irishman who had grown up in New York and been a successful marshal in Wyoming. His pay was $150 a month. One of his jobs was to enforce the ban on carrying firearms. Notices of this edict had been posted in public places, but cowhands from Texas had shot them full of holes. On Smith’s first Saturday night in Abilene, a town rowdy, known as Big Hank, decided to show up the new marshal. With his six-shooter in his belt, Hank swaggered up to Smith and begun to taunt him. “Are you the man who thinks he is going to run this town?” he asked. “I’ve been hired as marshal,” replied the officer. “I’m going to keep order and enforce the law.” “What are you going to do about the gun ordinance?” the bully inquired. “I’m going to see that it’s obeyed-and I’ll trouble you to hand me your pistol now.” With an oath, Big Hank refused. Smith sprang forward and felled him with a single blow on the jaw. Then he took the ruffian’s gun and ordered him to leave town at once-and permanently. Hank slipped out quickly, glad to escape the jibes of the street crowd. The new marshal’s first action impressed those who saw it, and news of what had happened spread to the cow camps on the prairies. In one camp on a branch of Chapman Creek, a braggart called Wyoming Frank bet that he could go into Abilene and wear his six-shooter. He rode in on Sunday morning and had a few drinks before Smith appeared. When Frank saw the marshal walking down the middle of the street, he went out and tried to engage him in a quarrel. Smith’s only answer was a request for the bully’s gun, which was refused. Smith, with steel in his eyes, advance toward Frank. The ruffian backed away, sidling through the swinging doors of a saloon where a crowd had gathered to see what might happen. Smith followed him inside and when Frank again refused to hand over his gun, the marshal pounced on him. With two swift blows, Smith knocked him to the floor, then took the gun and gave Frank five minutes to leave Abilene. The action so astonished the men in the saloon that, for a moment, they stood speechless. Then the shopkeeper handed Smith his gun and said, “That was the nerviest act I ever saw. You did you duty, and the coward got what he deserved. Here’s my gun. I reckon I’ll not need it as long as you’re marshal.” Others came forward offering their six-shooters. The marshal told them to leave the pistols with the bartender until they were ready to go back to their camps. Smith, who often rode up and down the streets on his gray horse, Silverheels, kept order so well that the town trustees raised his pay to $225 a month and gave him an assistant. He stayed on the job, without wasting any time drinking or gambling; and found no need to kill anyone, but with peace restored and the cowboys gone until next year’s drive, his job was discontinued.

Several Kansas cow towns produced the West’s best known frontier marshals. Of these by far the most courageous was the one who had the shortest career. Thomas James Smith, the marshal of Abilene during its boom days as the original terminus of the Chisholm Trail. Tom Smith, more than any other, exemplified western fiction writer William MacLeod Raine’s (Raine is one of my favorite authors) description of frontier peace officers: “They usually were quiet men. They served fearlessly and with inadequate reward. Their resort to the six-shooter was always in reluctant self-defense. Early in the cattle season of 1870, Abilene had tried several marshals, but no one had lasted more than a few weeks. Finally, on June 4, the town trustees hired Tom Smith, a husky Irishman who had grown up in New York and been a successful marshal in Wyoming. His pay was $150 a month. One of his jobs was to enforce the ban on carrying firearms. Notices of this edict had been posted in public places, but cowhands from Texas had shot them full of holes. On Smith’s first Saturday night in Abilene, a town rowdy, known as Big Hank, decided to show up the new marshal. With his six-shooter in his belt, Hank swaggered up to Smith and begun to taunt him. “Are you the man who thinks he is going to run this town?” he asked. “I’ve been hired as marshal,” replied the officer. “I’m going to keep order and enforce the law.” “What are you going to do about the gun ordinance?” the bully inquired. “I’m going to see that it’s obeyed-and I’ll trouble you to hand me your pistol now.” With an oath, Big Hank refused. Smith sprang forward and felled him with a single blow on the jaw. Then he took the ruffian’s gun and ordered him to leave town at once-and permanently. Hank slipped out quickly, glad to escape the jibes of the street crowd. The new marshal’s first action impressed those who saw it, and news of what had happened spread to the cow camps on the prairies. In one camp on a branch of Chapman Creek, a braggart called Wyoming Frank bet that he could go into Abilene and wear his six-shooter. He rode in on Sunday morning and had a few drinks before Smith appeared. When Frank saw the marshal walking down the middle of the street, he went out and tried to engage him in a quarrel. Smith’s only answer was a request for the bully’s gun, which was refused. Smith, with steel in his eyes, advance toward Frank. The ruffian backed away, sidling through the swinging doors of a saloon where a crowd had gathered to see what might happen. Smith followed him inside and when Frank again refused to hand over his gun, the marshal pounced on him. With two swift blows, Smith knocked him to the floor, then took the gun and gave Frank five minutes to leave Abilene. The action so astonished the men in the saloon that, for a moment, they stood speechless. Then the shopkeeper handed Smith his gun and said, “That was the nerviest act I ever saw. You did you duty, and the coward got what he deserved. Here’s my gun. I reckon I’ll not need it as long as you’re marshal.” Others came forward offering their six-shooters. The marshal told them to leave the pistols with the bartender until they were ready to go back to their camps. Smith, who often rode up and down the streets on his gray horse, Silverheels, kept order so well that the town trustees raised his pay to $225 a month and gave him an assistant. He stayed on the job, without wasting any time drinking or gambling; and found no need to kill anyone, but with peace restored and the cowboys gone until next year’s drive, his job was discontinued.