Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823-1893) was an educator and abolitionist. She was the first black woman to graduate from Howard University Law School and the first black woman to vote in a federal election. She helped President Lincoln enlist black men to fight in the Union and her house was frequently a safe haven in the Underground Railroad for slaves fleeing the South. After the war she became a school principal, and then a lawyer in Washington, D.C., at the age of sixty. She died in 1893 at age seventy from heart failure, with an estate valued at $150.

Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823-1893) was an educator and abolitionist. She was the first black woman to graduate from Howard University Law School and the first black woman to vote in a federal election. She helped President Lincoln enlist black men to fight in the Union and her house was frequently a safe haven in the Underground Railroad for slaves fleeing the South. After the war she became a school principal, and then a lawyer in Washington, D.C., at the age of sixty. She died in 1893 at age seventy from heart failure, with an estate valued at $150.

Journal Notes

That Pioneering Spirit

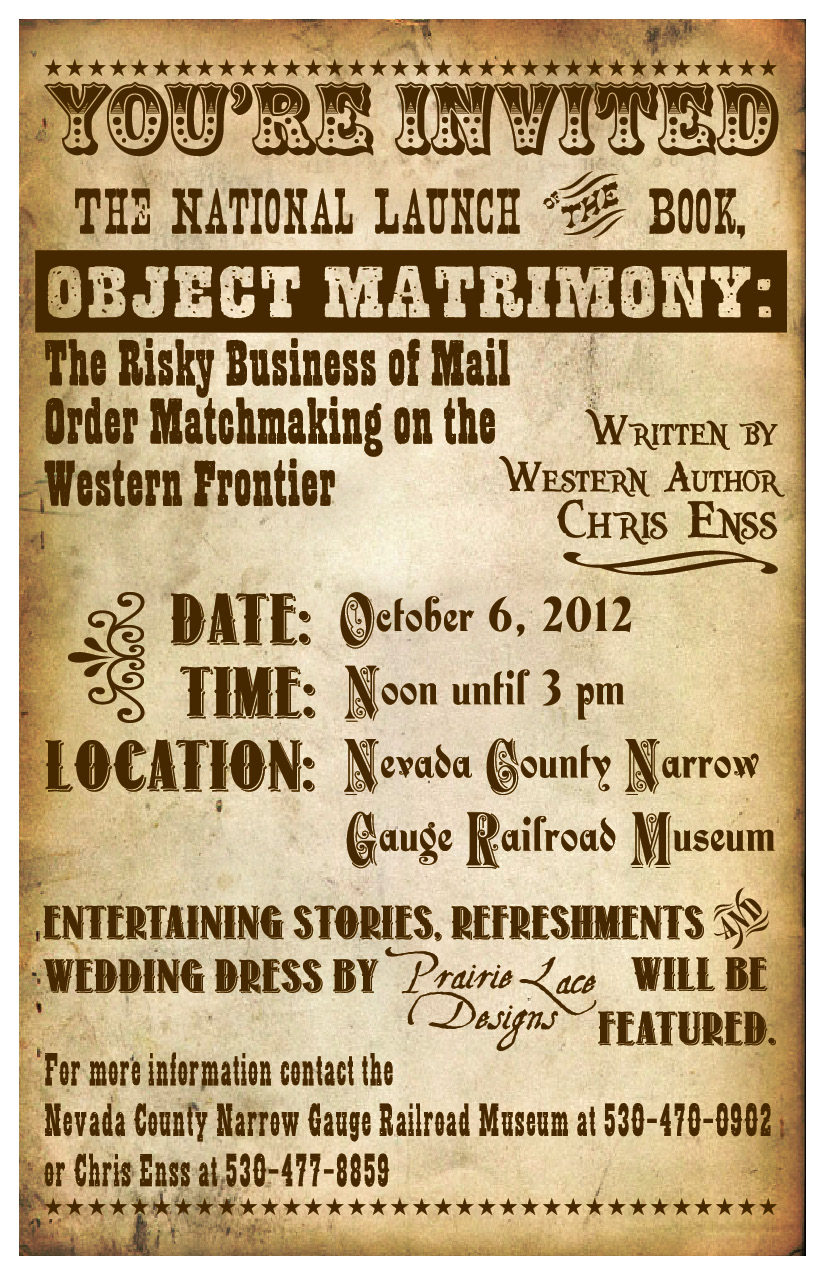

This month I’ll be focusing on tales of the brave frontier women of every profession and walks of life. Women who took on the rugged frontier to make a better life for herself and for the many thousands of women that came after her. Elizabeth Blackwell was a woman who defined the pioneer spirited. American’s first woman doctor was admitted to New York’s Geneva College in 1847 as a joke, and was expected to flunk out within months. Nevertheless, Blackwell prevailed and triumphed over taunts and bias while at medical school to earn her degree two years later. While in her last year of medical training, she was cleaning the infected eye of an infant when she accidentally splattered a drop of water into her own eye. Six months later she had the eyed taken out an had it replaced with a glass eye. Afterward, American hospitals refused to hire her. She then borrowed a few thousand dollars to open a clinic in New York City, which she called the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children. She charged patients only four dollars a week, if they had it, for full treatment that might cost at least two thousand dollars a day at the going rate. During the Civil War she set up an organization to train nurses, Women’s Central Association of Relief, which later became the United States Sanitary Commission. In 1910 age eighty-nine she died after a fall from which she never fully recovered. I’m off this morning to participant in a radio program called Insight on Capital Public Radio. The place to tune to on the dial between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m. is 90.9 FM KXJZ Sacramento; 90.5 FM KKTO Tahoe City/Reno; 91.3 FM KUOP Stockton/Modesto; 88.1 FM KQNC Quincy. The is the first radio interview leading up to the launch of the new book Object: Matrimony. Hope to see everyone at the launch event on Saturday, October 6 from noon to 3 p.m.. I’ll be giving away a wedding dress designed by Christian Michael Goodwin of Prairie Lace Designs. The dress was inspired by the gowns contained in the book Object: Matrimony and is a stunning garment!

This month I’ll be focusing on tales of the brave frontier women of every profession and walks of life. Women who took on the rugged frontier to make a better life for herself and for the many thousands of women that came after her. Elizabeth Blackwell was a woman who defined the pioneer spirited. American’s first woman doctor was admitted to New York’s Geneva College in 1847 as a joke, and was expected to flunk out within months. Nevertheless, Blackwell prevailed and triumphed over taunts and bias while at medical school to earn her degree two years later. While in her last year of medical training, she was cleaning the infected eye of an infant when she accidentally splattered a drop of water into her own eye. Six months later she had the eyed taken out an had it replaced with a glass eye. Afterward, American hospitals refused to hire her. She then borrowed a few thousand dollars to open a clinic in New York City, which she called the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children. She charged patients only four dollars a week, if they had it, for full treatment that might cost at least two thousand dollars a day at the going rate. During the Civil War she set up an organization to train nurses, Women’s Central Association of Relief, which later became the United States Sanitary Commission. In 1910 age eighty-nine she died after a fall from which she never fully recovered. I’m off this morning to participant in a radio program called Insight on Capital Public Radio. The place to tune to on the dial between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m. is 90.9 FM KXJZ Sacramento; 90.5 FM KKTO Tahoe City/Reno; 91.3 FM KUOP Stockton/Modesto; 88.1 FM KQNC Quincy. The is the first radio interview leading up to the launch of the new book Object: Matrimony. Hope to see everyone at the launch event on Saturday, October 6 from noon to 3 p.m.. I’ll be giving away a wedding dress designed by Christian Michael Goodwin of Prairie Lace Designs. The dress was inspired by the gowns contained in the book Object: Matrimony and is a stunning garment!

Schools of Old

Today’s American education system, quite frankly, ain’t doing so goodly or goodish. This country’s public schools couldn’t be more poorly funded and badly directed if the secretary of education were Marie Antoinette. If you’re lucky enough that you can afford a private school, then much of what follows probably won’t make sense to you, because unfortunately the majority of the problems are in the public schools, the ones called P.S., which is appropriate because they’re treated as an afterthought. Our public school system has become a giant monolithic substitute teacher, an overworked and underpaid civil servant with an impossible load on its back and a huge “kick me” sign on its behind. Maybe I’m not the best person to be addressing the subject of education. Frankly, when I was in school, I generated more C’s than a Spanish soap opera. But the subject of our public schools hits very close to my heart. For years I have been earnestly contributing vast amounts to the California school system. That’s right. I play the lottery. In days gone by, schools used to be orderly one-room red houses were kids would eagerly learn how to use impressive phrases like “in days gone by.” Today’s schools are replete with acts of violence. Violence and intimidation are such accepted parts of school for many kids these days that when the teacher tells students to raise their hands, just out of force of habit, they raise both of them. But I guess we should just be thankful that teachers dare to tell children anything nowadays. You see, being a teacher these days is not limited to the boring educational stuff anymore. Nooooo. You get to do so much more than just teach. You’re a one-man SWAT team, confiscating an AK-47 here, defusing a lunch box pipe bomb there. And then you’re so burnt out by the time you reach the apres-school parent/teacher meeting, you explode and tell some parents that they can take the college money they’ve been saving and buy themselves a septic tank because the only college their kid is going to has the word “beauty” or “clown” in front of it. If I hadn’t have had the brilliant teachers I did, in days gone by, I’m sure my life wouldn’t have turned out as well as it did…and quiet frankly my life stinks. But I digress…it was the teachers that made the difference. Unforgettable teachers like Virginia Upton, Augustus Bock, Gabe Kotter…. Perhaps if those teachers were still on the job the problems with the education system may not seem as insurmountable.

Love Lessons Learned

I’ve been working feverishly on a new book due to be released next fall entitled Love Lessons Learned by Women of the Old West. It’s been quite the education and since I’ve been focusing on teachers this month I thought I’d share a few things women like Calamity Jane and Agnes Hickok (Wild Bill’s wife) have taught me. Here’s what men wanted from women in the wild west: One – They wanted women to understand that they don’t care about clothes. Their own or anyone else’s. All they needed was a pair of Levis, one pair of boots, and another pair of better looking boots. That’s it. Two – Don’t talk to them while they’re trying to watch a boxing match or bear wrestling. Very simple. Match is over, they talk. Match is on, they don’t talk. Three – Hey, I’m sorry, but some men see a beautiful sunset and think, “You know the whiskey is better at the Long Branch in Dodge City than it is at the Oriental in Tombstone.” Four – Have a sense of humor. Without a sense of humor a relationship lasts about as long as John Wilkes Booths’ stage career. Five – Love them unconditionally. Help them out of the testosterone-induced fog they sometimes dwell in and lead them into the light. With the exception of bear wrestling these lessons seem applicable today. I had a wonderful time working on this title and am confident readers will enjoy it as well. I dedicated the book to George Brett. You’ll have to wait until the book is out in late 2013 to find out why.

The Hazards of Teaching

The indisputable reality of classroom disorder presented a valid case against appeals for an end to birching. Birching was a form of discipline used by school teachers in which a birch rod was used on a bare bottom. Many frontier school houses were not a stable of docile lambs as television and motion pictures about that time period would like us to think. Many of the children were downright brats-hostile, ungovernable and prone to violence. In addition, the assembly in one room of pupils ranging in age from five to sixteen, with some strays even in their twenties, was an invitation to trouble. Under these circumstances the teacher was more warden than instructor, their routine more physical than intellectual. Some school boards in selecting new teachers made it a rule to pick a strong, stoutly built individual because they believed “baseness and vulgarity prevailed among the older boys.” Biting, eye-gouging and slug and scuffle matches were favorite sports, but boys saved the most barbaric excesses for strangers. “Let a boy from one town visit another and he was fortunate if he escaped with his life. The intervillage feuds made it incumbent upon the boys of one town to stone, beat, thrash such a casual visitor.” Faced with such ruffians, many teachers did not last a week, some not even a day. “In the Coloma, California district,” one pioneer noted, “the boys have driven off the last two schoolmarms and liked the one afore them.” Some parents and school board members took macabre delight in the encounter between a new teacher and the “boys,” some of whom were 175-pound six-footers. For schoolmarms such confrontations were a horrific ordeal. Margaret Banes, a school teacher in the San Bernardino area recalled: “I stormed up and down… This pathetic pretense of courage, aided by the mad flourishing of my razor strap, brought forth… the expression of respectful fear on the faces of the young giants.” However, while Miss Banes’s pantomime succeeded in cowing heavyweights who were old enough to go to sea, other schoolmistresses encountered continual discipline problems. One of these, a Miss Vega, taught public school in Sacramento. On October 8, 1870, the young woman, said to be in feeble health, punished four boys for unruly behavior by shutting them in the school building after class was out. Finally, when she released them, Miss Vega is said to have given the boys “a slight reprimand.” Their response was immediate; they stoned her to death.

Save the Date

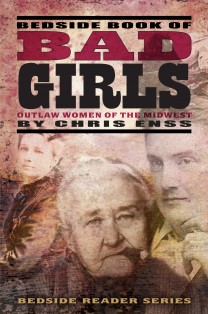

The Bedside Book of Bad Girls

There’s another new book on the way. Here’s a little about the exciting title. Author Chris Enss goes behind the lipstick and petticoats to reveal the real women who outran the law and upended gender stereotypes across America’s Heartland in her latest book Bedside Book of Bad Girls: Outlaw Women of the Midwest. Readers will meet Flora Mundis, expert horse thief and jail breaker; murderess Elizabeth Reed, the first and only woman hanged in Illinois; Belle Black and Jennie Freeman, who shot their way through hold ups and alongside the men of the Wyatt-Black Gang; and Anne Cook, bootlegger and madam, who killed her own daughter in cold blood. Illustrated with historical photographs, Bedside Book of Bad Girls: Outlaw Women of the Midwest uncovers the true lives long veiled by the glamour of dime novels and sensational tabloid accounts. Cozy up (if you dare) with these women, both sensuous and sinister, as they rampage across the Midwest. Chris Enss has written more than twenty books on the subject of women of the Old West, including Hearts West: Mail-Order Brides on the Frontier and Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman. Bedside Book of Bad Girls: Outlaw Women of the Midwest was published by FarCountry Press will be available in book stores October 15, 2012. Visit www.chrisenss.com for more information about the book or to schedule an interview.

There’s another new book on the way. Here’s a little about the exciting title. Author Chris Enss goes behind the lipstick and petticoats to reveal the real women who outran the law and upended gender stereotypes across America’s Heartland in her latest book Bedside Book of Bad Girls: Outlaw Women of the Midwest. Readers will meet Flora Mundis, expert horse thief and jail breaker; murderess Elizabeth Reed, the first and only woman hanged in Illinois; Belle Black and Jennie Freeman, who shot their way through hold ups and alongside the men of the Wyatt-Black Gang; and Anne Cook, bootlegger and madam, who killed her own daughter in cold blood. Illustrated with historical photographs, Bedside Book of Bad Girls: Outlaw Women of the Midwest uncovers the true lives long veiled by the glamour of dime novels and sensational tabloid accounts. Cozy up (if you dare) with these women, both sensuous and sinister, as they rampage across the Midwest. Chris Enss has written more than twenty books on the subject of women of the Old West, including Hearts West: Mail-Order Brides on the Frontier and Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman. Bedside Book of Bad Girls: Outlaw Women of the Midwest was published by FarCountry Press will be available in book stores October 15, 2012. Visit www.chrisenss.com for more information about the book or to schedule an interview.

Object Matrimony

Press Release

For Immediate Release:

Lonely Hearts Advertise;

Object Matrimony

Grass Valley, CA. – Optimistic men and women pioneers expressed their desire for a spouse in advertisements that ran in popular frontier newspapers and magazines. A new book entitled Object Matrimony: The Risky Business of Mail-Order Matchmaking on the Western Frontier offers readers an entertaining look at the serious business of finding a husband or wife by mail-order in the wide-open days of the Old West.

Desperate to strike it rich or eager for free land, men went west alone and sacrificed many creature comforts. Only after they arrived at their destinations did some of them realize how much they missed female companionship. One way for men living on the frontier to meet women was through personal ads placed in newspapers such as Matrimonial News. Eventually a man might convince a woman to join him in the West, and in matrimony.

Object Matrimony: The Risky Business of Mail-Order Matchmaking on the Western Frontier was written by Chris Enss. Enss is the author of more than two dozen books published by Globe Pequot Press on the subject of women of the Old West. The national launch of the book will be held on Saturday, October 6 at the Nevada County Narrow Gauge Railroad Museum in Nevada City, California from noon until 3 p.m.. In addition to sharing stories about frontier mail-order brides and marriage brokers with guests that attend the launch festivities, musical entertainment and refreshments will also be available. A wedding dress made by fashion designer, Christian Goodwin for Prairie Lace Designs, will be given away at the launch as well.

Object Matrimony: The Risky Business of Mail-Order Matchmaking on the Western Frontier will be available in bookstores everywhere in October. For more information contact the Nevada County Narrow Gauge Railroad Museum at 530-470-0902 or Chris Enss at 530-477-8859

# # #

Corporal Punishment

Some frontier teachers had a harsh rule they strictly enforced. They believed “Lickin’ and larnin’ goes together, No likin, no larnin.” (Now I’d start with “lickin” the teacher here, not only for the idea but for such poor spelling, but that’s just me). The forgoing dogma was basic to the educational philosophy of the old days. Lessons were regarded as a commodity to be pressed into reluctant vessels – the pupils – and a birch rod or hickory sick was used to accomplish this end. Legally in loco parentis, teachers relied upon it more heavily to enforce discipline, their devotion to scholarship often measured by the number of backsides they had reddened. Humanitarians, a tiny minority, thought otherwise, among them a former schoolmaster named Walt Whitman, who complained of the “military discipline” of the schools. “The flogging plan is the most wretched item yet of school-keeping,” he thundered. “What nobleness can reside in a man who catches boys by the collar, and cuffs their ears?” But such criticism posed no threat to corporal punishment, which was extremely hailed as a healthy and indispensable practice. (One inveterate disciplinary referred to his weapon as “my board of education.”) And concomitant with this belief went an austere mistrust of improvements to the physical plant because they were a “luxury.” A Washington Territory schoolmarm’s plea for the installation of toilets was turned down by the school board, which advised her that “there were plenty of trees in the yard to get behind.” Even her suggestion to replace the single well dipper with more hygienic individual cups was denied as being “undemocratic.”

School Days

Rural schools were handicapped not only by size – one room for all ages – but by the quality of instruction they dispensed. Teaching was an occupation of minimal prestige, with low pay, low standards and a high turnover rate. It was said that anybody could be a teacher, and while no doubt some were fine, dedicated individuals, most proved shiftless and unimaginative-products of the very systems they perpetuated. Because children supplied essential farm labor, the school year lasted barely twelve weeks, from Thanksgiving through early spring. It was hardly enough time for learning, or to encourage a teacher who genuinely sought results. And the salaries – in 1888-89 an average of $42.43 a month for men and $38.14 for women, grudgingly relinquished from frugal budgets-attracted mostly young men in transit to a profession or women who declared themselves schoolmarms to get away from a suffocating home life. Sometimes the teacher was a girl younger than several of her pupils, and almost as ignorant. Teachers were compensated for their low pay by being allowed to alternate free board and lodgings with various families. But many could not endure the accompanying scrutiny given their private lives and quit in disgust after a term or two, leaving the curriculum in chaos. Clarence Darrow recalls: “We seldom had the same teacher for two terms of school, and we always wondered whether the new one would be worse or better than the old.” To read more about teachers on the rugged plains read Frontier Teachers: Stories of Heroic Women of the Old West. Go to www.chrisenss.com for more information.