“That James W. Marshall picked up the first piece of gold, is beyond doubt. Peter L. Weimer, who resides in this place, states positively that Mr. Marshall picked up the gold in his presence.”

The Coloma Argus Newspaper – 1855

Prospectors and settlers were amazed at the ease with which gold was recovered among the rocks and streams of the California foothills in early 1848. The first gold was discovered by James Wilson Marshall, a carpenter by trade and an employee of Captain John A. Sutter. Marshall was wandering along the bank of the American River where he was building a sawmill when he noticed a peculiar golden stone in the bedrock. It was a find that changed the course of western history.

By most accounts James Marshall was a surly man who kept to himself. He was born in Lambertsville, New Jersey in 1810 and from an early age worked with his father learning the trade of carpentry, carriage making and wheel righting. In 1828, he left home to start his own life. He settled in the Midwest farming on land in Kansas, Indiana and Illinois.

Farming proved to be an unsuccessful venture for him and in 1844 he headed west along the Oregon Trail to Puget Sound. Later he traveled down the Sacramento River arriving in California in 1845. He quickly found work at Sutter’s Fort and in a short time had acquired several acres of land and livestock.

Towards the end of August 1847, Captain Sutter and Marshall formed a co-partnership to build and operate a sawmill on a site 54 miles east of the fort. Mr. P.L. Weimer and his family were hired on to accompany Marshall to the location to cook and labor for the builders constructing the mill. The building began around Christmas and gold was discovered a little more than a month later. Marshall glanced down into the river water and something caught his eye. He leaned forward to get a better look and saw something shining in the gravel. “Gold!” Could it be gold?” He said to himself.

Marshall showed the rock to the workers around him. Many of them suspected the material to be iron pyrite, or fool’s gold. Marshall decided to return to Sutter’s Fort to verify the discovery. Before he left he swore the mill workers to secrecy. In exchange for their silence they would be given the chance to prospect on Sundays and after work.

As Marshall rode swiftly across the beautiful countryside towards the Fort he was troubled by a complication with the land where the gold was found. The property was purchased by Captain Sutter from Mexico and the local Indians, but since the sale of the land California had become a territory of the United States. Marshall was concerned the United States government would not honor Sutter’s prior claim once the gold strike was made public. When Marshall unveiled his findings to Sutter, Sutter was sure that the rock was gold and he too was concerned about the claim. Marshall’s hope was that the news of the discovery would be kept quiet long enough for Sutter to be granted full legal title with the new government. It was not to be however. Marshall and Sutter’s employees began to talk, sharing the news of the find with teamsters and trappers. Within 6 weeks of the discovery Sutter’s entire staff at the fort had deserted him and Marshall’s workers abandoned the mill.

Marshall informed the new prospectors in the area that he and Sutter owned a 12 mile tract of land along the river banks. He charged them 10 percent of their take for the privilege of working the gravel. His claim discouraged many miners, but when some of them made their way to San Francisco with full pockets the rush was on. A band of frustrated miners who felt they were being denied access to the gold defied Marshall. They overtook the half completed mill and killed several men who sided with Marshall.

After being pushed off the stake that he found, Marshall left the area in disgust. He traveled around Northern California searching for another strike, but was never fortunate enough to locate one. Marshall returned to the Coloma area in 1857 where he bought some land and started a vineyard. High taxes and increased competition eventually drove him out of business.

In 1872, the California State Legislature awarded Marshall with a 2 year pension. The funds were in recognition of his role in the Gold Rush. The $200 a year pension was renewed in 1874 and 1876, but lapsed in 1878.

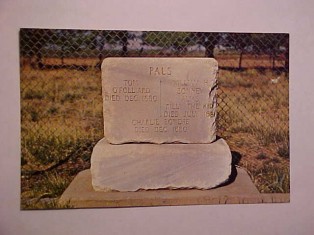

James Marshall died a pauper on August 10, 1885, in Kelsey, California. He was 73 years-old. He was buried in Coloma near the site of the vineyard he once owned. The monument atop his grave features a granite stature of Marshall pointing towards the place he found the glittery substance that dazzled a nation.