The Kellys are coming May 27.

Hide your valuables.

Chris Enss and Meyer Lansky, II, grandson of Meyer Lansky and author of The Lansky Legacy: The Life and Letters of Meyer Lansky

I'm looking forward to hearing from you! Please fill out this form and I will get in touch with you if you are the winner.

Join my email news list to enter the giveaway.

"*" indicates required fields

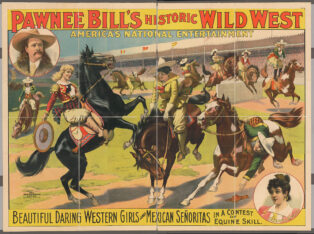

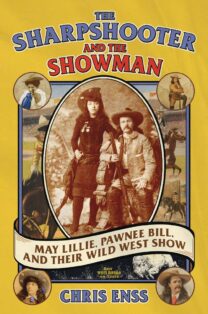

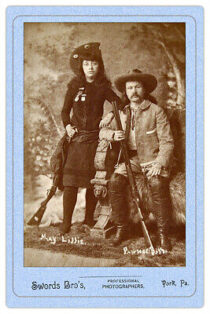

The storm that overcame Bloomington, Illinois, on August 28, 1895, started slowly, the peripheral winds rustling the trees. The large crowd at the McLean County amphitheater attending Pawnee Bill’s Wild West show paid little attention to the light drizzle tapping on the ceiling of the canvas enclosure. Their focus was on May Lillie and her mustang. The “Queen of the Markswomen” had coaxed her horse into a gallop, and she was shooting glass balls strategically placed around the performance arena. It wasn’t until the conclusion of her act when she stopped firing her gun that the sound of a large clap of thunder could be heard. Patrons recognized the weather had taken a serious turn.

A torrent of rain fell followed by strong gusts of wind, testing the resolve of the tent’s roof and walls. The wind screamed around the heavy flaps of the covering, pulling hard at the stakes keeping the tent in place. It was clear the unrestrained gale was determined to take down anything in its path. Pawnee Bill urged the audience and the program’s cast and crew to find alternate shelter. Many of the 5,000 plus patrons didn’t heed the warning and refused to move. Only when the wind began tearing the tent in pieces, blowing it down in the process, did the people scramble to find a way out from under the sheets of canvas.

Every person who was able to run picked up their pace, holding futile hands skyward in an attempt to protect themselves from the torrential downpour. Moments after the canopy collapsed, the stadium seats came down with a crash. Further chaos ensued and a general stampede followed; women and children were crushed and walked upon. By the time patrons made their way out of the muddy fairgrounds they were soaked to the skin, but no one had been hurt. People took refuge under ticket wagons, in box stalls, and the tents still standing that belonged to the Indians in the show.

All the property, sets, and equipment belonging to the Wild West show was drenched in the storm. Pawnee Bill and his players gathered the meager remains of the program that could be salvaged and left for the next scheduled engagement in Champaign, Illinois.

The early days of Pawnee Bill’s Wild West Show’s 1895 season were plagued with unfortunate incidents such as the powerful rainstorm in Bloomington. Performers were injured after being thrown from their horses, some cast members suffered with various illnesses, and inclement weather hurt ticket sales. What helped improve business along the way were the daring cowgirls who joined May in the arena. Women performing tricks most thought only men could or should attempt were a major draw. Women such as equestrian Mexican Rose, the charming senorita and the most daring and reckless horsewoman in the world, and cowgirls Nadine White and Bertha Smith who rode at breakneck speeds around the arena retrieving items placed in the dirt and climbing under their horses and up the other side while the animal raced along, were astonishing.

I’ll be at a variety of locations throughout Oklahoma from May 5 through the 12th giving book presentations.

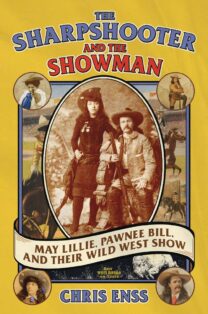

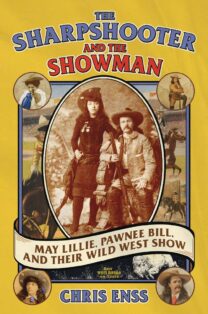

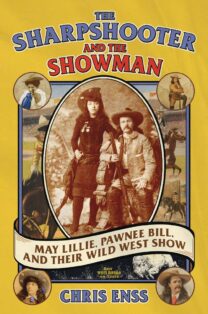

Visit the Events Section of the www.chrisenss.com site for more information and to enter to win a copy of The Sharpshooter and the Showman.

5.0 out of 5 stars A Great History of How the Old West Was Shared Around the World

Reviewed in the United States on April 27, 2025

I loved this book! I had never heard of Pawnee Bill and May Lillie, nor their Wild West Show. I did think that William Cody’s Wild West Show was the most famous.The more I read about Pawnee Bill and his sharpshooter wife, May, the more I became interested in their lives, their business and how they handled such a large exposition with so many diverse people, animals and acts. I am sorry I missed out! I don’t think an enterprise like this will ever be recreated again.

I believe that individually they had their strengths but together they were a powerhouse!!! And the old photos were so much fun to look at! I felt very bad about the loss of their children. So hard! And reading that May died before Bill was also sad. It seemed that the two of them were inseparable!

In conclusion, this was one of the best history books I ever read. I learned a lot about the Wild West, the way that women stood out in this era, and the politics of the time.

I highly recommend this book and look forward to reading more of this author’s (Chris Enss) books!

I'm looking forward to hearing from you! Please fill out this form and I will get in touch with you if you are the winner.

Join my email news list to enter the giveaway.

"*" indicates required fields

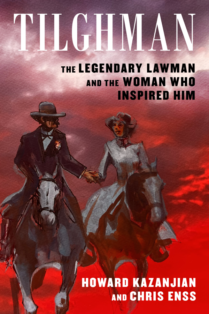

Tilghman: The Legendary Lawman and The Woman Who Inspired Him (Two Dot, 2024) is the story of the intertwined history of Bill Tilghman’s career and his wife, Zoe’s, life after his tragic death. The narrative of the story switches back and forth between the events of Bill Tilghman’s law enforcement career and Zoe’s life after his passing as she seeks to raise their children and write a biography of her legendary lawman’s life.

Major events of Tilghman’s epic life as a lawman are retold by Zoe in a way that meshes with the life she is living as his widow. The book is a compelling read that captures the struggle and beauty of life and death in the west in this biography within a biography. Authors Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss bring the story of a wife’s love to life as she seeks to honor her late husband’s legacy amidst the struggle of her own life. The attention to detail and use of primary sources garners an authenticity to the writing and brings the story of the Tilghmans’ to life on the page.

The storytelling propelled me through this rich and interesting story of the history of the Tilghmans. The writing style of Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss is a smooth narrative that gives the reader a satisfying deep dive into the details without feeling like a clunky, laborious read. The book is engaging and is unique in its presentation of a story within a story.

Rating: 5 Nuggets out of 5.

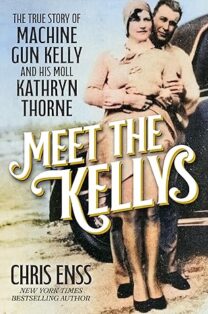

“Chris Enss superbly documents George “Machine Gun” Kelly and his wife Kathryn Thorne in his book Meet the Kellys. I appreciate Enss utilizing ephemeral documents, such as newspaper clippings and first-person interviews in addition to court recordings. Enss dedicated research culminates in a fast-paced read, true crime read. I appreciate Enss’s narrative structure: 1) Meet the Kellys; 2) Learn about the Kellys’s bootleg and bank robber years; 3) See how the Kellys evolved from low criminals to kidnappers; 4) Read the correspondence letters; 5) Observe court room proceedings; 6) Capture the Kellys 7) What happened next. This structure feels like a crime podcast–in the best of ways. Place this on your TBR list for May27, 2025.” NetGalley Reviews

May Lillie and Pawnee Bill, along with their Wild West troupe, made their way from Baltimore, Maryland, south to Atlanta, Georgia, traveling north again to Michigan, New York, and into Canada. Gordon routinely sent letters to the editor at the Wichita Star that included clippings from the many locations the Wild West show played. The editor would then make mention of Gordon’s correspondence and let readers know how the Lillies were doing and how large the crowds were that the program attracted. “Audiences from Montgomery to Montreal all agree that the Lillie’s shows are worth going a long way to see,” the August 27, 1890, edition of the Wichita Star noted.

Numerous fans of Pawnee Bill attended the program to see the frontiersman they had read about in Dime Novels. May Lillie had many followers as well. The press frequently reported on her appearances in and out of the performance arena and she was highly sought after as a result. While in Ohio with the show during the 1890 tour, May was honored by a civic organization in Cleveland.

The award presented to her was a gold-mounted whip. She and Pawnee Bill were also invited to attend a formal ball which was help to further celebrate her equestrian accomplishments. When she learned a prize would be given for the “handsomest costume” at the gala, she was determined to win. Adorned in an elaborate Indian dress, May arrived at the party riding her horse Hunter. She led the mustang into the ballroom where the most elite of the town’s citizenry had gathered. Her entrance caused a significant stir and most everyone found her style refreshing. May left the event with the prize for her costume and was asked to lead a procession of Cleveland’s high society ladies in an impromptu parade down main street.

May’s admirers came out in droves on October 18, 1890, to watch her perform a death-defying trick. The Lillies’ show was playing a week-long engagement in Atlanta, Georgia, and guests had been invited to meet the cast and tour the canvas-covered homes of the Indians as well as the other troupe members. Visitors had been promised a shooting exhibition by May and she didn’t disappoint. A daring spectator volunteered to help her with the stunt that involved having an apple shot off his head. The apple-shot was fairly common in Wild West shows, but finding someone who had the nerve to risk the unerring aim of the shooter could be a challenge.

All eyes were on May as she took her place twenty-five yards from the volunteer. She raised her rifle, pointed it at the apple, fired, and hit the mark. The captivated audience erupted in applause.

I'm looking forward to hearing from you! Please fill out this form and I will get in touch with you if you are the winner.

Join my email news list to enter the giveaway.

"*" indicates required fields

May sat in the middle of her bed in her room at her parents’ home in Philadelphia, rereading the letters Gordon had sent her. Among the correspondence scattered about were newspaper clippings of Gordon’s work with those who were committed to the opening of Oklahoma’s unassigned lands to white settlements. One of the first letters to his wife after agreeing to lead the Boomers described the scene as he arrived in Wichita on Saturday, December 22, 1888.

“As the train pulled in, I saw the platform, the street, in fact all the open space in sight literally packed with people all ‘Hurrahing’ and waving handkerchiefs and flags in the throes the greatest excitement. As the train quieted down, I could hear the strains of a brass band playing “The Conquering Hero Comes.”

“What’s going on?” I asked a gentleman standing next to me. By this time everyone was on their feet peering from the windows of the coaches.

“Why, Pawnee Bill is on the train. He is coming here to organize and lead the Boomers into Oklahoma, he replied.

“I almost sank in my tracks. Never before had I been received in such glorious manner, and here I was, dressed in a threadbare suit, worn by a season’s work, and actual holes in the crown of my big sombrero. And I to be the center of this enthusiastic reception.

“As I reached the platform of the coach, I was grabbed by leaders Marsh Murdock of the [Wichita] Eagle, George Dixon, Harry Hill, Joe Rich and a number of others. I was rushed to an open carriage with the brass band in the lead and with this crowd following. They escorted me to the Del Monico Hotel which was to be headquarters of the colonization company of which I was to be president and leader. That evening I sat at a formal banquet in the Del Monico and responded to speeches of welcome.”

Articles in newspapers The Wichita Star and Wichita Eagle elaborated on the scene that awaited Gordon as he stepped off the train in the Kansas town.

“Besides the fifty teamsters already to move upon the coveted country there are not less than 300 families in Wichita who have been quietly gathering here during the past month who will go into the territory,” the December 24, 1888, edition of the Wichita Star read. “Arkansas City and Caldwell will furnish as many more. Excitement is running high over what is termed a secret organization to invade the Territory, but the Boomers are defiant. Pawnee Bill says that he wants to be arrested and tried by the government and adds that if Congress will not pass the Springer Bill he will test the law in the proper court relative to the Oklahoma country being public lands.* It is thought now that 2,000 unarmed men from here will go into Oklahoma at an appointed time which is given out as January 10.

“The people have waited the progress of the Springer bill in congress and no one can be found who believes it will be passed. Major Lillie, alias Pawnee Bill, is known all over the west as a great scout and Indian guide and his name as the leader of the invaders is bringing in many additional men who want to join their fortunes with the colonists. When asked how many Boomers would go into the country he said that he could muster 10,000.”

May had no doubt her husband would allow himself to be arrested if the Springer bill didn’t pass. He was compelled to lead the Boomers into the Territory without a proclamation issued from the government, but she hoped it wouldn’t come to that.

I'm looking forward to hearing from you! Please fill out this form and I will get in touch with you if you are the winner.

Join my email news list to enter the giveaway.

"*" indicates required fields