Enter now to win a copy of

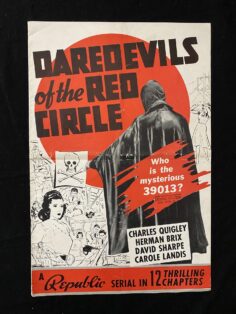

Cowboys, Creatures, and Classics: The Story of Republic Pictures

Not too long ago, I was in Pasadena with Howard Kazanjian promoting the book we coauthored entitled Straight Lady: The Life and Times of Margaret Dumont, “The Fifth Marx Brother.” It was a lovely event. With the exception of one woman who was wearing a designer jumpsuit with rhinestones, twenty bracelets on each wrist, and way too much Jean Nate, everyone was kind and complimentary. The lady in the jumpsuit declined to purchase a copy of the book and wasn’t shy about letting us know why. “I read a few chapters of your work in Barnes and Noble,” she began. “Maggie Dumont and Groucho Marx had a long-standing affair and you never mentioned it your book. It’s disgraceful that you call yourselves nonfiction writers. It’s useless to pretend that you’ll ever be widely read.”

Before I was able to share with her that in fact, Dumont and Marx were never romantically involved, she turned and stormed out of the building. The smell of Jean Nate still hovered in the air hours after she’d gone. I thought of a dozen things I could have said in response to the rudeness. Things like, “If you’re going to say something that dumb, you could at least fake a stroke” or “There’s a bus leaving in a few minutes. Please be under it.” Instead, I said nothing. And then she posted her remarks on Amazon and I wished I had followed her out of the store and shouted, “So, that’s what a mummy looks like without the bandages!”

The truth is that authors with infinitely more talent than I ever hope to have had endured harsh words from readers. One reviewer called William Golding’s book Lord of the Flies, “…completely unpleasant.” A critic of Truman Capote’s book In Cold Blood noted, “One can say of this book-with sufficient truth to make it worth saying: ‘This isn’t writing. It’s research.’” Another noted of Thomas Berger’s book Little Big Man, “…a farce that is continually over-reaching itself. Or, as the Cheyenne might put it, Little Big Man Little Overblown.”

Noel Coward once said, “I love criticism just as long as it’s unqualified praise.” I think I agree. This month I’m giving away a copy of Cowboys, Creatures, Classics: The Story of Republic Pictures.

Bring on the unqualified praise!