Enter now to win a copy of the new book

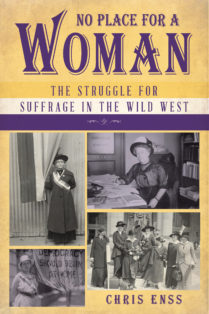

No Place for a Woman: The Fight for Suffrage in the Wild West

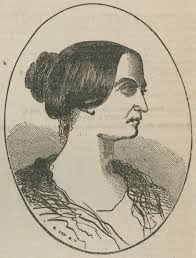

When suffragist Susan B. Anthony boarded the passenger car of the Union Pacific Railroad in Ogden, Utah, in late December 1871, the train was filled to capacity. Men, women, children, livestock, baggage, and crates containing food and supplies were being loaded onto the vehicle bound for Chicago. Weary and carrying an oversized satchel bulging with clothing, books, and papers, the fifty-one-year-old woman climbed aboard and began the slow procession past the throngs of people occupying various seats and berths. She snaked her way toward the semi-private compartments until she found the one, she was to occupy for the duration of the trip. The pair Anthony would be traveling East with had already arrived and made themselves comfortable. She smiled at the congenial-looking couple as she entered. California congressman Aaron A. Sargent politely got to his feet to help her stow away her bag. He introduced himself, then introduced his accomplished wife, Ellen, to Anthony, who returned the kindness.

Not long after Anthony was settled, Ellen admitted to being familiar with her work. Anthony’s crusade to acquire the right to vote for women had been covered in the Sacramento newspapers as well as the publications in Nevada City, California, where the politician and his family lived. She had joined the fight for woman’s suffrage in 1852. Since that time, she had traveled from town to town, inspiring women to fight for equal rights. The crusade, which initially began in Seneca Falls in New York in 1840, had expanded westward. Once Wyoming granted women the privilege to cast their ballots, suffrage rose in territories beyond the Mississippi to battle for the opportunity to do the same. Crusaders reasoned if women could gain that right state by state the federal government would be persuaded to pass an amendment making it law.

From June to December of 1871, Anthony had traveled more than thirteen thousand miles, delivered 108 lectures, and attended close to two hundred rallies on the issue of woman’s suffrage. There were others such as Emily Pitts Stevens, who helped form the California Woman Suffrage Association, and physician and minister Anna Howard Shaw who had joined the fight and were hosting meetings to inform and educate women about the movement. It was essential that the message of equality be heard in every mining community, fishing village, and major city from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Women needed to be encouraged to petition for enfranchisement. They needed to be reminded they were entitled to speak for themselves and stand against fathers and husbands voting for them. Anthony and the other dedicated suffragists had been able to share the message with women in Kansas, Wyoming, Utah, Washington, and Oregon; they had great hope the ladies in California would back reform.

Anthony couldn’t have found a more receptive audience for her message than Congressman Sargent and his wife. Ellen had founded the first suffrage group in Nevada City, California, in 1869, and Aaron was in full support of giving women the vote. The Sargents had moved to California from Massachusetts in 1849 and settled in Nevada City in 1850. In addition to owning and operating the newspaper the Nevada Daily Journal, Aaron was an attorney and former U. S. senator. Ellen was a homemaker and mother who was active in the Methodist Church. She firmly believed that women could not attain their highest development until they “had the same large opportunities and the same large chances as her brothers have.”

To learn more about how women won the right to vote in the West read

No Place for a Woman: The Struggle for Suffrage in the Wild West