According to Kate is coming to bookstores everywhere on October 1.

In honor of her imminent arrival this month is dedicated to

Wild Women like Kate Elder.

Mollie Moses, a disheveled woman in her 40s, sat alone in her rundown Kentucky home, crying. She wiped her eyes with the hem of her tattered black dress and glanced up at a portrait of William Cody hanging over a cold fireplace. On the dusty coffee table in front of her lay several letters carefully bound together with a faded ribbon. The woman’s feeble fingers loosened the tie and slowly unfolded one of the letters. Tears slid down her cheeks as she read aloud.

My Dear Little Favorite…I know if I had a dear little someone whom you can guess, to play and sing for me it would drive away the blues who knows but what someday I may have her eh!… I am not very well, have a very bad cold and I have ever so much to do. With love and a kiss to my little girl – From her big boy, Bill.

William Cody – 1885

Mollie closed her eyes and pressed the letter to her chest, remembering. From the moment she first saw Buffalo Bill Cody at a Wild West performance, she had been captivated by him. He was fascinating – a scout, hunter, soldier, showman, and ranchman. Mollie was swept away by his accomplishments, reputation, and physical stature.

In September of 1885 the enamored young woman from Morganfield, Kentucky, set about to win the heart of the most colorful figure of the era.

Mollie was an attractive widow, intelligent and sophisticated. The letters she wrote to Cody reflected her maturity and interested Buffalo Bill. Her correspondence did not read like that of a love-struck girl but of an experienced woman. The death of her husband and only child many years prior had transformed the once impetuous girl into a driven, determined woman. Mollie was also educated and well read, and an accomplished artist and seamstress.

Cody found those aspects of her character quite appealing. He responded to her letters often, forwarding his itinerary to her as well, with hopes the two could meet at some point. When at last they did, he was pleased to see that she was as lovely as she was intelligent. On November 11, 1885, the couple began a six-month affair.

Your kind letter received. Also, the beautiful little flag which I will keep and carry as my mascot, and every day I wave it to my audiences I will think of the fair donor. I tried to find you after the performances yesterday for I really wished to see you again…It is impossible for me to visit you at your home much as I would like to have done so. Many thanks for the very kind invitation.

I really hope we’ll meet again. Do you anticipate visiting the World’s fair at New Orleans if you do will you please let me know when you are there…Enclosed please find my route. I remain yours.

William Cody – November 1885

As the romance between Mollie and Bill grew, she extended numerous invitations for him to come and visit her. Managing the Wild West Show demanded a lot of his time, and he was unable to get away as often as Mollie wanted.

My Dear…you say you are not my little favorite or I would take the time to come to see you. My dear don’t you know that it is impossible for me to leave my show. My expenses are $1,000 a day and I can’t. I would come if it were possible and I can’t say when I can come either, but I hope to someday.

William Cody – March 1886

Cody could not break free from his business, but Mollie persisted. She requested that some of his personal mementos be sent instead.

“If you cannot be here, I must have something of you near me,” she wrote him.

My Dear Little Favorite…Don’t fear I will send a locket and picture soon. Little Pet, it’s impossible for me to write from every place. I have so much to do. But will think of you from every place. Will that do? With Fond Love…Will.

William Cody – April 1886

Molly worried about Cody’s wife, Louisa, and the hold their twenty-year marriage had on him. In one of Cody’s letters to Mollie, he tried to ease her troubled mind and heart.

My Dear Little Favorite…Now don’t fear about my better half. I will tell you a secret. My better half and I have separated. Someday I will tell you all about it. Now do you think any the less if me? I wish I had time to write you a long letter to answer all your questions and tell you of myself, but I have not the time and perhaps it might not interest you…With love and a kiss to my little girl from her big boy.

William Cody – April 1886

Despite his constant reassuring, Mollie was not convinced that Cody and his wife were destined for divorce. When it became clear to her that Cody could not or would not fully commit to her, she requested a spot in his show.

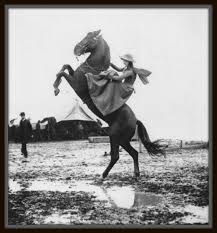

She reasoned that this was the only way she would be able to be with him all the time. Mollie was not without talent. She was a fine horsewoman, and that, along with her romantic involvement with Cody, helped persuade him to invite her to join his troupe.

Mollie and Buffalo Bill were to meet in St. Louis, a scheduled stop for the show. Mollie was to come on board as a performer at that time. To make her feel welcome and show his affections, Cody purchased his lover a horse. The act endeared him to her even more.

My Dear Mollie…I presume you are getting about ready to come to St. Louis. Wish you would start from home in time to arrive in St. Louis about the 2nd or 3rd of May. Go to the St. James Hotel if I ain’t there to meet you. I will be there any how by the 3rd. I have got you the white horse and fine silver saddle. Suppose you have your habit. Will be glad to see you. With love, W.F.C.

William Cody – 1886

Mollie’s days with Wild West Show were difficult. Adapting to the rigorous traveling schedule was hard and riding her horse day after day left her stiff and sore. Eventually Mollie lost interest in the famous program and tired of trying to win over the heart of its general manager.

Within a few years after parting with Cody, Mollie’s financial situation worsened dramatically. Mollie Moses returning to her home in Kentucky, where she fell into a life of poverty. She was forced to sell off many of the mementos Cody gave her and live off the generosity of strangers to keep herself in food. The two souvenirs she would never part with were the silver saddle and Cody’s picture.

Rodents shared her house with her – rats she called her “pets.” One evening her pets bit her severely, causing her to become ill. She eventually died of complications from the bites. She was forty-three years old. Historians speculate that the demise of her relationship with Buffalo Bill left her despondent and without the will to live.

According to Kate arrives in book stores on October 1.

Enter to win a copy of Kate’s story now.