Enter now to win a copy of

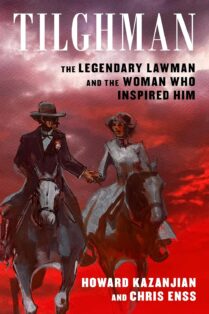

Tilghman: The Legendary Lawman and the Woman Who Inspired Him

In mid-October 1885, two men ambled down the Jones and Plummer Trail, 120 miles from the Kansas border, toward the Cimarron River. Marshal Bill Tilghman was in the lead, his eyes fixed on the spot the riders would have to ford the swollen waterway. He had a tight grip on a bald-faced mare trailing behind him. Atop the animal was a horse thief named George Synder. He was a dark-complected man in his mid-thirties with a thin moustache and a gaunt intensity that wasn’t entirely healthy looking. Tilghman had journeyed to Mobeetie, Texas, to arrest Synder for stealing a horse that belonged to a politician from Great Bend named J. C. Briggs.

It wasn’t the first time Tilghman had made a long trip to apprehend a criminal. Unlike other lawmen who had to encroach on another jurisdiction to make an arrest, Tilghman insisted on acquiring the necessary writs from the officers overseeing the area he planned to invade. He expected the same courtesy to be shown him from law enforcement seeking to detain an offender in his domain.

In the first pages penned about his life and work, Zoe made note of such professional courtesies practiced by the marshal. “My husband’s career in law enforcement began in Dodge City when the country west of the Mississippi was finding its way,” she wrote. “Bill traveled to Okla homa in 1889 just before the first land rush in the nation. He served the rough Territory for thirty-five years as U. S. deputy marshal, sheriff, chief of police, and special aide to governors. His peers admired his ethics and outlaws feared his tenacity. In the end, when a new kind of frontier opened during the brawling oil boom of the 1920s, Bill gave his life as he had lived it—in the cause of decency and order.” Zoe could envision her husband escorting Synder to jail and contemplating his early years on the open range. His family had moved to Kansas after the military closed the fort where William Matthew Tilghman Sr. had been employed as a sutler at Fort Dodge, Iowa, selling provisions to the troops.

“He grew up on the plains, and a gun was rarely far from his hand,” Zoe noted about Tilghman’s upbringing. “At that time, in 1862, his father and oldest brother Richard enlisted in the Union Army and fought in the Civil War. Tilghman had to do the work on the farm near Atchison, Kansas, and furnish his mother Amanda and six others with food, which mostly consisted of rabbits and prairie chickens. When he wasn’t feeding the stock, milking, and gathering corn, he was practicing his shooting. In time, he was able to provide his mother, brothers, and sisters with geese and turkeys for their meals.”

I'm looking forward to hearing from you! Please fill out this form and I will get in touch with you if you are the winner.

Join my email news list to enter the giveaway.

"*" indicates required fields

In 2026 America celebrates a monumental birthday – its 250th! ”America250” will be

an epic year of celebrating our past, present and hopes for the future. While traditional

historic reflections are focused on extraordinary male contributions to the founding

and building of America, this documentary series will reveals the outstanding, but

never heard of, women who not only helped shape our young country, but whose lives

reverberate 250 years later. The stories we will tell are of the lives of bold, pioneering

women who saw no limitations at a time when women had few options in life. Our

daughters today will see the women whose shoulders they are standing on.

The documentary series entitled Plain Genius: Women Who Helped Build America

will leverage the historical authorship of Chris Enss, best-selling author and skilled

storyteller. Her meticulously researched books provide a road map to primary materials

and archives necessary to present these women in rich and compelling detail. Each

episode will feature four women who had a profound impact on our nation’s early

development, AND the lasting legacy of their gifts to our culture. We will interweave

archival visual and audio materials with cutting-edge reenactments, interviews with

historians, legacy women, and appropriate celebrities.

In addition to being a legendary marshal, Tilghman was a father of seven children and a faithful companion to his second wife Zoe for more than two decades. His violent death in November 1924 devastated Zoe and the three boys they had together. Tilghman had encountered numerous criminals over the course of his career and had come through the gun battles relatively unscathed.

When he took the job of bringing about stability in the untamed oil town of Cromwell, Zoe anticipated he’d take care of the work and return home to live out his days with her and their boys. She never imagined he would be gunned down in the line of duty. Now a widow at forty-three, Zoe was faced with how to continue without the man she cherished and admired. Not only would she be responsible to make sure nineteen-year-old Tench, seventeen-year-old Richard, and twelve-year-old Woodie were cared for on her own, but the debts the couple had accumulated fell solely to her to pay.

Tilghman was buried on November 5, 1924, and on November 10, 1924, creditors came calling. Zoe was the literary editor of the newspaper Harlow’s Weekly. Her salary alone would not cover the family’s needs and outstanding bills. She had been pondering the situation for weeks, in between reading Tilghman’s detailed memoirs of the various manhunts, posse rides, shootouts, and arrests in which he participated over the course of his life as a sheriff or marshal. She reviewed with considerable pride the newspaper clippings he had kept about the outlaws he apprehended.

Although he’d stayed on the job longer than any of his colleagues and squared off against more renegades than lawmen such as James Butler Hickok, Seth Bullock, or Virgil Earp, Tilghman’s name wasn’t as recognizable as most of the others in the field. Among the correspondence Zoe had received from men and women expressing their sorrow over Tilghman’s death were newspaper articles about Wyatt Earp’s work in motion pictures, his friendship with film star William S. Hart, and the biography in the works about the lawman and his gunfighter life. Zoe had never personally met Earp but knew of him from her husband.

She believed Tilghman’s experiences were at least as daring and exciting as anything Wyatt Earp had done, and spanned a far greater number of years. The idea to write a book about Tilghman’s adventures wearing a badge began forming in Zoe’s mind a month after his passing and was rekindled after reading of a possible volume on Earp. She was convinced readers would appreciate the tales of Marshal Tilghman’s efforts to tame the territory beyond the Mississippi.

According to Zoe, “My husband was one of the West’s greatest peace officers. He hunted down famous outlaws and killed when he had to. But Tilghman was more than an expert gunman who fought on the side of the law. He and other men who held dangerous jobs as sheriffs and marshals did the work of civilization along the whole frontier.”

I'm looking forward to hearing from you! Please fill out this form and I will get in touch with you if you are the winner.

Join my email news list to enter the giveaway.

"*" indicates required fields

Late in the summer of 1884, a pair of wild-eyed, trail-stained strangers wandered into Dodge City, Kansas. Both were heavily armed when they entered the Long Branch Saloon. The bartender noticed their guns and informed the men the weapons weren’t allowed in town. The men announced to all in earshot that they hadn’t any intentions of surrendering their guns and defied the law to take their six-shooters from them.

The two grabbed a bottle of whiskey and a couple of glasses and proceeded to a nearby table where they started drinking. In between drinks the pair loudly threatened to kill anyone with a badge who came near them. Marshal Tilghman’s reputation as an effective peace officer had reached beyond Dodge City, and the belligerent customers dared the well-known lawman to square off against them. “We hear tell he’s fast on the draw,” they shouted. “He’s got a chance now to prove it. Somebody go tell him that if he’s tired of living, we’re ready to help him end it.”

A man named Sampson let the marshal know what was going on and, in spite of the informant’s warning to stay away, Tilghman picked up his pistols and headed out of his office. As he left, he told Sampson if he didn’t go, gunslingers from all over the Territory would ride into Dodge ready to oppose him.

When Marshal Tilghman entered the saloon, patrons and employees scattered. The resolute lawman made his way to the mouthy drifters and instructed them to give up their guns. “They’re not allowed in town,” he told them. The three men eyed one another for a few brief moments and then one of them quickly drew his weapon. Before he could get off a shot, Tilghman had drawn and fired his gun at the man.

The second of the duo pulled his pistol but he didn’t get far. He was on the floor with a bullet in his chest before the smoke from Tilghman’s first shot had cleared. The marshal retrieved the dead men’s weapons and ordered a handful of cowboys who were taking refuge behind the bar to help carry the bodies to the mortician’s office.

I'm looking forward to hearing from you! Please fill out this form and I will get in touch with you if you are the winner.

Join my email news list to enter the giveaway.

"*" indicates required fields

The Kiowas kicked their horses into a gallop toward the cowboys. Tilghman and the man with him took off in the direction they came. The packhorses they had with them as well as the stray cattle raced to keep up. The Indians divided into two parties, both hurrying after the cowhands as fast as their rides would take them. Tilghman and his coworker urged their horses to go even faster, and the animals did. The chase continued for several minutes with the Kiowas closing the gap on the exhausted cattle and pack-animals trying to keep up. Eventually the braves captured the cows and horses. Some stayed behind with the livestock while others maintained the pursuit of Tilghman and his companion.

The gap between the Kiowas, Tilghman, and the other cowhand widened and narrowed throughout the chase. Tilghman considered stopping to shoot the pursuers but was convinced killing one or several of the warriors would only cause more problems in the long run. The cowboys believed their only option was to outrun the Kiowas. The Indians doggedly followed the two men into a canyon, forcing the pair up a steep hillside. When the cowhands reached the top, they realized they were trapped. Far below them on the other side was a stream that was swollen from the recent rains. Tilghman quickly surmised they would have to jump if they hoped to survive.

The cowboys dismounted and coaxed their horses to make the leap first. They watched the animals plummet forty feet into the water. The dazed and slightly confused horses emerged unhurt from the death-defying jump. They swam to the bank of the stream, stumbling over rocks until they got their footing where they stood huddled together, shaking from the experience.

Tilghman and the cowhand with him leapt from the precipice minutes after making sure the horses had made it through the ordeal. The pair hit the water hard and popped to the surface moments later. Tilghman looked at the cliff towering over them to see if the warriors were at the summit. Seeing no one, the cowhands pulled themselves out of the rampaging stream and hurried to their horses. The still shaking animals could barely move beyond a walk. Tilghman and his cohort managed to lead the horses to an outcropping of rock. By then, the Kiowas were lined along the ridge. Tilghman removed his Sharps rifle from the holster on his saddle and fired a shot in the warrior’s direction. The Kiowas quickly climbed off their horses and flattened themselves on the ground. They didn’t return fire or attempt to follow the cowhands down the embankment.

I'm looking forward to hearing from you! Please fill out this form and I will get in touch with you if you are the winner.

Join my email news list to enter the giveaway.

"*" indicates required fields

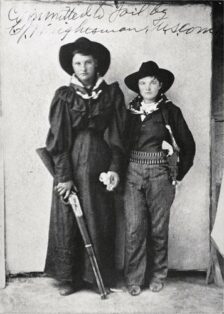

Deputy marshal Bill Tilghman nudged his galloping horse in the side with his spurs to encourage the animal to run faster. The lawman was after a fugitive who had gotten a bit of a head start and whose ride was swift and agile. The horse’s ability to keep up with the outlaw’s mount had a great deal to do with the rider in the saddle. Tilghman was a solid, broad-shouldered man in his early forties and the desperado he was pursuing was a petite, seventeen-year-old woman. Jennie Metcalf, known in the Oklahoma Territory as Little Breeches, led her horse across the prairie around the town of Pawnee with ease. The ride was so fluid she managed to remove her Colt six-shooter from the waistband of the oversized trousers she was wearing, turn around in her seat and fire a volley of shots at Tilghman.

The marshal grimaced as he spurred his horse on and lifted his Winchester out of the saddle holster. It was August 18, 1895, and the sun was a ball of fire. The wind at his face was like the breath of a furnace. He was hot and tired and in no mood to take part in a gun battle with a teenager. Tilghman hadn’t anticipated the young woman would make a run for it when he set out to arrest her and her cohort, Annie McDoulet alias Cattle Annie, for stealing horses.

The pair’s misdeeds extended far beyond horse thievery. For several months, the women had been working with the Doolin Gang. In 1893, William “Bill” Doolin organized the group comprised of some of the most ruthless criminals in the region. They robbed banks, stagecoaches, and trains. Marshal Tilghman and two other deputy marshals, Heck Thomas, and Chris Madsen had been on their trail for years, but the gang was always one step ahead of them. It was clear someone was helping them to navigate around law enforcement’s efforts to apprehend the felons.

After the Doolin Gang robbed the United States Army payroll near Woodward, Oklahoma, in March 1894, the three officers discussed what they knew about each crime and what dubious characters seemed to always be in the general vicinity. Little Breeches and Cattle Annie were the prime suspects. The three men believed the women had been scouting for the gang, acting as their lookout, and keeping them in supplies. Tilghman was convinced the key to the Doolin Gang’s demise was to capture the misguided youth who were aiding and abetting them.

I'm looking forward to hearing from you! Please fill out this form and I will get in touch with you if you are the winner.

Join my email news list to enter the giveaway.

"*" indicates required fields

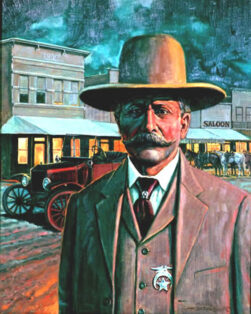

He was steely eyed, hard riding and straight shooting; a soft-spoken, tee-totaling lawman who never drew his gun…unless he meant to use it. Among other things he was also a buffalo hunter, Indian fighter, rancher horse breeder, saloon keeper, politician…even a movie maker. His name was Bill Tilghman and of all the heroes of the Old West he was one of the last, one of the most heroic, and a legend in his own time. Tilghman is about his life and the woman who memorialized his adventures.

Tilghman began his career in Dodge City in 1878 when his friend Bat Masterson, newly elected sheriff, made him under sheriff. Still going strong in 1924, the 70-year-old Tilghman was called out of retirement to help rid Cromwell, Oklahoma, of bootlegging gangsters. In 1878 the bad guys rode horses; in 1924 they drove Piece-Arrows and Fords and flew airplanes.

Frontier outlaw or prohibition hoodlum, Tilghman fought them all. In his lifetime he saw the vast herds of buffalo disappear from the great plains and Oklahoma transformed from Indian territory and outlaw haven into homesteading land and booming oil country. Oklahoma City evolved from a collection of muddy tents and shacks into a thriving metropolis. It was a dramatic transformation and Bill Tilghman helped make it happen.

Beside him through most of that transformation was his wife, author Zoe Agnes Stratton. Zoe not only had an up-close view of the various outlaws her husband pursued, but was instrumental in preserving those daring exploits on paper. The short stories and books she wrote about Tilghman’s life as a law enforcement agent helped make him a celebrated figure throughout the West. Zoe recorded Marshal Tilghman’s capture of such criminals as the Doolin Gang, Cattle Annie and Little Britches, and the Jennings brothers. She also wrote of his friendship with such well-known figures as Marshal Heck Thomas, Marshal Bass Reeves, and Judge Isaac Parker.

When Bill Tilghman was gunned down in 1924 by a corrupt federal agent, Zoe had to find a way to continue on and financially support the two sons she’d had with the lawman. She earned a living writing about each case her husband had taken on during his career. Zoe hoped her sons, Richard and Woodie, would do better than their father had when he was young as the old frontier days were past, but Bill Tilghman’s brace of pistols remained symbolic of the family’s fate.

In October 1929, nineteen-year-old Richard was killed in a crooked gambling game, along with his friend James Chitwood, a farmer. Seventeen-year-old Woodie was arrested soon after for killing the man who shot his brother. Woodie was arrested for manslaughter and sentenced to five years in prison. Zoe wrote about those heartbreaking events as well. Her body of work is recognized as some of the state’s finest historical writing.

Tilghman: The Legendary Lawman and the Woman Who Inspired Him is not only the story of a brave man – it’s a colorful, exciting history of the last days of the Western frontier. It’s also the story of a woman, desperate to hold onto her family and honor the life of the man she loved so dearly.

I'm looking forward to hearing from you! Please fill out this form and I will get in touch with you if you are the winner.

Join my email news list to enter the giveaway.

"*" indicates required fields

Clothing historians believe that no couple made more of an impact on western fashion than George and Elizabeth Custer. George, the “Boy General,” carried on his duties as commander of the Seventh Cavalry dressed in fringed buckskin breeches and a jacket, a navy-blue shirt with a wide falling collar and a red cravat. His men so admired the look that they adopted it for the entire regiment.

Custer’s sense of style extended to women’s clothing as well. Elizabeth accompanied her husband on field maneuvers dressed in hoop skirts that measured five yards around the bottom. At times, the prairie wind would blow the skirt up and expose her petticoat. So, George designed an outfit for his wife that included a military-style riding jacket, a pleated undershirt, and a less cumbersome skirt. Strips of lead were sewn into the dress hems to keep it weighted down in a strong breeze.

I'm looking forward to hearing from you! Please fill out this form and I will get in touch with you if you are the winner.

Join my email news list to enter the giveaway.

"*" indicates required fields