Enter for a chance to win a copy of

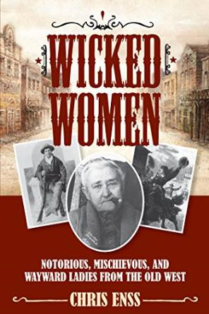

Wicked Women:

Notorious, Mischievous, and Wayward Ladies from the Old West

Libby Thompson twirled gracefully around the dance floor of the Sweetwater Saloon in Sweetwater, Texas. A banjo and piano player performed a clumsy rendition of the house favorite, “Sweet Betsy From Pike.” Libby made a valiant effort to match her talent with the musician’s limited skills. The rough crowd around her was not interested in the out of tune playing; their eyes were fixed on the billowing folds of her flaming red costume. The rowdy men hoped to catch a peek at Libby’s shapely, bare legs underneath the yards of fabric on her skirt. Libby was careful to only let them see enough to keep them interested.

Many of the cowboy customers were spattered with alkali dust, grease, or plain dirt. They stretched their eager unkempt hands out to touch Libby as she pranced by, but she managed to avoid all contact. At the end of the performance, she was showered with applause, cheers, and requests to see more. Libby was not in an obliging mood. She smiled, bowed, and hurried past the enthusiastic audience as she made her way to the bar for a drink.

A surly bartender served her a glass of apple whiskey, and she headed off to the back of the room with her beverage. When she wasn’t entertaining patrons, Libby could be found at her usual corner spot by the stairs. A large, purple, velvet chair waited for her there along with her pets, a pair of prairie dogs. As Libby walked through the mass of people to her spot, she saw three grimy, bearded men surrounding her seat. One of the inebriated cowhands was poking at her animals with a long stick.

“Boys, I’d thank you kindly to stop that,” she warned the unruly trio. The men turned to see who was speaking then broke into a hearty laugh once they saw her. Ignoring the dancer they resumed their harassment of the small dogs. The animals batted the stick back as it neared them, and each time the men would erupt with laughter.

Libby watched the three for a few moments then slowly reached into her drawstring purse and removed a pistol. Pointing the gun at the men she said, “Don’t make me ask you again.” The drunken cowhands turned to face Libby, and she aimed her pistol at the head of the man with the stick. Laughing, the man told her to “go to hell.” “I’m on my way,” she responded, pulling the hammer back on the gun. “But I don’t mind sending you there first so you can warn them,” she added. The cowboy dropped the stick, and he and his friends backed away from Libby’s chair. One by one they staggered out the saloon. Libby put the gun back into her purse, scooped up her frightened pets, scratched their heads, and kissed them repeatedly.

To learn more about the wild ladies on the rugged frontier read

Wicked Women:

Notorious, Mischievous, and Wayward Ladies from the Old West

Today’s focus isn’t on The Pinks, but that doesn’t mean you can’t still

Today’s focus isn’t on The Pinks, but that doesn’t mean you can’t still