Last chance to enter to win a copy of the new book

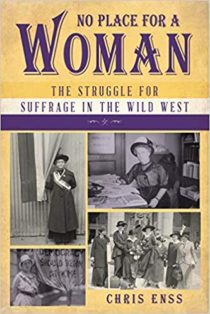

No Place for a Woman: The Fight for Suffrage in the Wild West

The watershed year of 1848, in the strife-filled period before the American Civil War, saw the rise of women at Seneca Falls who declared that they were equal to men and not just worthy of the vote—deserving of it by the divine right of being human and citizens. Of course, while that organized group was determined to fight for the equality of women, they were fighting at a time when the equality of all people was the central question of the day. The denial of rights to women and blacks (freed and slave) was incongruous with the enlightenment ideals of democracy and the hopes of a new republic—but those in charge of the new republic were having a tough time seeing past the blinders of their race and sex.

During and immediately after the Civil War, many abolitionists and suffragists worked together toward the common goal of ending slavery, and in 1866, after the end of the war, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony formed the American Equal Rights Association intending to continue the fight for voting and civil rights for all citizens. That was when things got complicated.

As part of the process of reconstructing the Confederate states into the Union, Congress became absorbed in passing the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution, amendments that defined both who qualified for citizenship regardless of race and sex and that drew criteria for who could vote in elections. The interpretation of the language in both amendments drew challenges from all sides—and ultimately split the previously strong movement in favor of suffrage for all former slaves and women into factions who were in favor of the political expedience of allowing males of African descent the right to vote regardless of their previous state of servitude while letting women’s interest be pushed to the side.

But the split was more complicated than that. In the late 1860s, a further division erupted between women’s suffrage advocates after the Fourteenth and Fifteenth were the law of the land. The faction led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony favored taking swift action to enact national woman suffrage through yet another constitutional amendment. The faction led by Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell, and Julia Ward Howe—once staunch allies of Stanton and Anthony in the struggle for suffrage and the end to slavery—favored using the clause of the Fifteenth that gave the states the right to decide who could vote. They wanted to approach the woman suffrage issue one state at a time.

To learn more about how women won the right to vote in the West read

No Place for a Woman

Visit www.chrisenss.com to enter to win a copy of No Place for a Woman