Enter to win a copy of

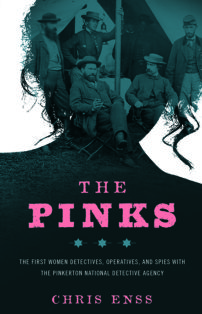

The Pinks:

The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency

Several months before the start of the Civil War, Kate Warne was masquerading as a Southern sympathizer and keeping company with women of refinement and wealth from the South. When war did break out, those women were unafraid to express how much in favor they were of the Rebels. Some of them were secretly supplying the Confederate forces with information they had acquired using their feminine wiles. Kate was tasked with staying close to opponents of the government who were seeking to overthrow it and secure proof that secrets were being traded.

For weeks Kate had been monitoring the movements of Mrs. Rose Greenhow, a Southern woman believed to be engaged in corresponding with Rebel authorities and furnishing them with valuable intelligence. By late August 1861, Allan Pinkerton and a handful of his most trusted operatives, including Kate, had compiled enough evidence against Rose that a warrant for her arrest was granted. She was outraged when Pinkerton detective agents invaded her home and began gathering boxes of secret reports, letters, and official, classified documents. She called the agents “uncouth ruffians” and objected to her home being searched.

Pinkerton and his team left none of Rose’s possessions intact in their quest to extract all suspicious paperwork. The headboards and footboards of all the beds were taken apart, mirrors were separated from their backings, pictures removed from frames, and cabinets and linen closets were inspected. Coded letters were found in shoes and dress pockets. Among the items found in the kitchen stove were orders from the War Department giving the organizational plan to increase the size of the regular army, a diary containing notes about military operations, and numerous incriminating letters from Union officers willing to trade their allegiance to their country for a romantic interlude with Mrs. Greenhow.

According to Rose’s account of the inspection of her house and the seizure of many, sensitive letters, the “intrusion was insulting.” One of the investigators at the scene complimented her on the “scope and quality” of the material found. It was “the most extensive private correspondence that has ever fallen under my examination,” the operative confessed. “There is not a distinguished name in America that is not found here. There is nothing that can come under the charge of treason, but enough to make the government dread and hold Mrs. Greenhow as a most dangerous adversary.”

Pinkerton had hoped to keep the arrest quiet, but Rose’s eight-year-old daughter made that impossible. After witnessing the operatives foraging through her room and the room of her deceased sister, she raced out the back door of the house shouting, “Mama’s been arrested! Mama’s been arrested!” Agents chased after the little girl. Having climbed a tree nothing could be done until she decided to come down.

A female detective Rose referred to in her memoirs as “Ellen” searched the suspected spy for vital papers hidden in her dress folds, gloves, shoes, or hair. Nothing was found. Historians suspect the operative Rose referred to as Ellen was Kate Warne. Kate divided her time between guarding the prisoner and questioning leads that could help the detective agency track and apprehend all members of the Greenhow spy ring. Rose realized quickly that Kate was not someone to be trifled with, and she kept her distance.

In the days to come, several women suspected of being a part of Rose’s spy ring were also arrested and kept under lock and key with their leader at her house. The Rebel informer’s home was referred to as Fort Greenhow, and newspaper reporters flocked to the house of detention hoping to get a look inside and converse with the prisoners. The January 18, 1862, edition of Boston Post included an article about the home for inmates and described what it looked like. The article reported that Rose and her daughter had been confined to the upstairs portion of the residence and all other guests occupied the downstairs.

“We were admitted to the parlor of the house, formerly occupied by Mrs. Greenhow,” the article continued. “Passing through the door on the left and we stood in the apartment alluded to. There were others who had stood here before us we have no doubt of that, men and women of intelligence and refinement. There was a bright fire glowing on the hearth, and a tete-a-tete (an S shaped sofa on which two people sit face to face) was drawn up in front. The two parlors were divided by red curtains and in the backroom stood a handsome rosewood piano with pearl keys upon which the prisoners of the house, Mrs. G. and her friends had often performed.

“The walls of the room were decorated with portraits of friends and others, some on earth and some in heaven, one of them representing a former daughter of Mrs. Greenhow, Gertrude, a girl of seventeen or eighteen summers, with auburn hair and light blue eyes, who died sometime since.

“Just now, as we are examining pictures, there is a noise heard overhead, hardly a noise, for it is the voice of a child soft and musical. ‘That is Rosey Greenhow, the daughter of Mrs. Greenhow, playing with the guard,’ said the Lieutenant who noticed our inquisitive expression. ‘It is a strange sound here; you don’t often hear it, for it is generally quiet.’ And then the handsome face of the Lieutenant relaxed into a shade of sadness. There are many prisoners here, no doubt of that, and maybe the tones of this young child have dropped like rains of spring upon the leaves of the drooping flowers! A moment more and all is quiet, and save the stepping of the guard above there is nothing heard.”

To learn more about Kate Warne, the cases she worked, and the other

women Pinkerton agents read

The Pinks:

The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency