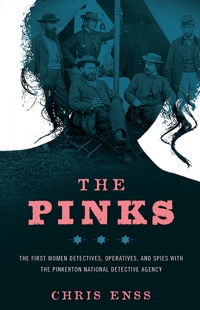

Enter to win a copy of

The Pinks:

The First Women Detectives, Operatives, and Spies with the Pinkerton National Detective Agency

An article in the May 14, 1893, edition of the New York Times categorized women as the “weaker, gentler sex whose special duty was the creation of an orderly and harmonious sphere for husbands and children. Respectable women, true women, do not participate in debates on the public issues or attract attention to themselves.” Kate Warne and the female operatives that served with her defied convention, and progressive men like Allan Pinkerton gave them an opportunity to prove themselves to be capable of more than caring for a home and family.

Kate’s daring and Pinkerton’s ingenuity paved the way for women to be accepted in the field of law enforcement. Prior to Kate being hired as an agent, there had been few that had been given a chance to serve as female officers in any capacity.

In the early 1840s, six females were given charge of women inmates at a prison in New York. Their appointments led to a handful of other ladies being allowed to patrol dance halls, skating rinks, pool halls, movie theaters, and other places of amusement frequented by women and children. Although the patrol women performed their duties admirably, local government officials and police departments were reluctant to issue them uniforms or allow them to carry weapons. The general consensus among men was that women lacked the physical stamina to maintain such a job for an extended period of time. An article in an 1859 edition of The Citizen newspaper announced that “Women are the fairer sex, unable to reason rationally or withstand trauma. They depend upon the protection of men.”

The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union played a key role in helping to change the stereotypical view of women at the time. The organization recognized the treatment female convicts suffered in prison and campaigned for women to be made in charge of female inmates. The WCTU’s efforts were successful. Prison matrons provided assistance and direction to female prisoners, thereby shielding them from possible abuse at the hands of male officers and inmates. Those matrons were the earliest predecessors of women law enforcement officers.

Aside from women hired specifically as police matrons, widows of slain police officers were sometimes given honorary positions within the department. Titles given to widows meant little at the time; they were, however, the first whispers of what would eventually lead to official positions for sworn police women.

Even with their limited duties, police matrons in the mid to late 1800s suffered a barrage of negative publicity. Most of the commentary scoffed at the women’s infiltration into the field. The press approached stories about police matrons and other women trying to force their way into the trade as “confused or cute” rather than a useful addition to the law enforcement community.

Allan Pinkerton’s decision to hire a female operative was all the more courageous given the public’s perception of women as law enforcement agents. Kate Warne had the foresight to know that she could be especially helpful in cases where male operatives needed to collect evidence from female suspects. She quickly proved to be a valuable asset, and Pinkerton hoped Hattie Lewis also known as Hattie Lawton would be as effective.* Hattie was hired in 1860 and was not only the second woman employed at the world famous detective agency, but some historians speculate was the first, mixed race woman as well.

The Pinks 5

I'm looking forward to hearing from you! Please fill out this form and I will get in touch with you if you are the winner.

Join my email news list to enter the giveaway.

"*" indicates required fields