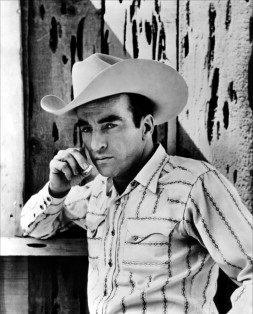

If you die at the height of your fame, you can achieve immortality. If you live long enough for your fame to fade, you are forgotten. Montgomery Clift belongs in the latter category. In the early 1950s his moody, sensitive performances in A Place in the Sun, From Here to Eternity and Red River made him a major heartthrob. More than that, he added an introspective, psychological dimension to those roles which made him the idol of two men who would become the most popular actors of the decade, Marlon Brando and James Dean. But by the time Clift died a little over a decade later, his obituary wasn’t front-page news. And unlike other ill-fated stars of the decade, such as James Dean and Marilyn Monroe, the forty plus years since Clift’s death have produced only three or four biographies of his life. Clift had been on Broadway since he was 14, but fame in Hollywood seemed to strike him differently. Three years after his first film, in 1948, he was treated for alcoholism. Some said it had to do with his insecurity concerning his many clandestine homosexual affairs. But whatever the cause, it turned a thoughtful, delicate actor into an inarticulate one. He soon began mixing pills, mostly depressants, with his drinks. He threw food at dinner parties, threw childish tantrums, and suffered blackouts. By the late 1950s movie studios were reluctant to cast Clift, especially since his last few films had not been hits. He showed up in supporting and cameo roles, but even then his long scenes would have to be chopped up because he couldn’t remember all his lines for one take. In 1966, after not working at all for four years, Clift was cast as the lead in The Defector. It was a B-movie spy thriller and he knew it, but he treated it as his comeback. To prove to the studios he was reliable star, he insisted on performing all his own stunts, including a grueling swim in the freezing Danube River, even as he was suffering from phlebitis and cataracts and was trembling. Clift, still drinking, seemed happy with his performance. But then he saw a rough version of the movie. In it the 45-year-old actor looked like an old man. He returned to New York that summer deeply depressed and drinking even more. In mid-July he saw or spoke to several of his remaining friends. He was uncharacteristically emotional, and some later believed he was telling them goodbye. He spent Friday night, July 22, alone in his bedroom, which was not unusual. But his male nurse was concerned when he found the door locked at 6 a.m. Saturday. He discovered Clift lying face up on his bed, dead, and wearing only his glasses. An autopsy revealed that the faded film star had suffered a heart attack. But one friend, reflecting on Clift’s last thirteen years, called it “the slowest suicide in show business.”

Follow Me

© 2025 Chris Enss | Privacy Policy | Design by Winter Street Design Group | Login