Take a chance. Enter to win a copy of the book

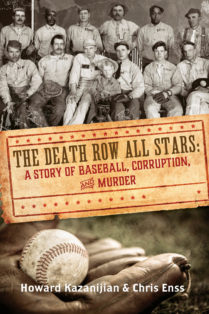

The Death Row All Stars:

The Story of Baseball, Corruption, and Murder

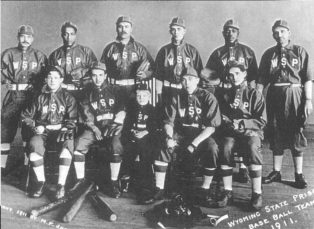

In the summer of 1911, the grass around the baseball diamond at the Wyoming State Penitentiary was a brilliant green. The slabs of canvas at home plate and at all three bases were faded white and dented by cleats that had tramped over them or slid into the sides. The walls surrounding the field were covered with scuff marks from fly balls and home runs. Ivy vines crawled along the stone backdrop in spots, breaking free to the other side.

By the summer of 1912, the outfield grounds were discolored and dominated by weeds. Only a handful of photographs existed to show that the Death Row All Stars had ever played there. Some of the pictures featured team members circling the bases after smacking the ball hard. “All baseball loves a hitter,” a reporter at the Wyoming Tribune wrote about the game in April 1912. “The skill of a pitcher is rejected. The successful defensive work of infield and outfield, the one-handed stop or the running catch must ever arouse enthusiastic cheers; but when all is said and done, the wielder of the big stick is the giant that stirs the imagination and the hero worship of the fans.

“No thrill equals that which comes when a home player sends the ball ringing off his bat safely to the outfield. As the number of bases gained by such a hit increases, so does the excitement mount. When one of those drives wins a game, its maker is a hero—the fan can conjure no reward that is adequate. Those low in spirit whose countenance is lifted by such an achievement cannot fully express their appreciation for helping them to see, if only for a moment, beyond their despair.”

Professional baseball clubs like the Boston Rustlers and the Saint Louis Browns, teams that ended the year of play with a 0.300 record or worse, could set their sights on improving when the 1912 season began. Not so with the All Stars. Once the ball club was disbanded in 1911, there would never again be a baseball team at the Wyoming State Penitentiary organized and managed by the warden. Inmates could gather players together for solitary games but would never again gather players together for solitary games but would never again be allowed to compete outside the walls of the prison.

By the time the 1912 baseball season rolled around, Warden Alston’s thoughts were more on keeping order at the facility than playing the game. Prisoners were refusing to work, and many had been disobeying orders and had been placed in solitary confinement in the prison’s dungeon. According to the May 8, 1912, edition of the Wyoming Tribune, Rawlins was thrown into a high state of excitement when ten convicts burrowed out of that dungeon. “The appearance of the men from the break in the dungeon wall at about 11 o’clock last night prompted the summoning of the guards,” the article reported. “It resulted in the immediate capture of eight of the ten convicts. Two of the convicts, however, got over the prison wall and as of noon today have not been captured, although a posse was sent to scour the country immediately upon a count showing that two men were missing.

“While none of the convicts captured in the yard were armed and were placed in their cells without difficulty, it is believed that the men who got away must have had some assistance, as no trace has been obtainable of either of them.”

Inmates who continued to be unhappy about the demise of the penitentiary baseball team and who were upset with what many convicts referred to as inhumane treatment and conditions at the prison wrote letters to Governor Carey asking that he “appoint an impartial non-political body of men to investigate the conditions at the prison.”

To learn more about inmates who played ball for their lives read the book The Death Row All Stars:

The Story of Baseball, Corruption, and Murder.