Enter now to win a copy of the new book

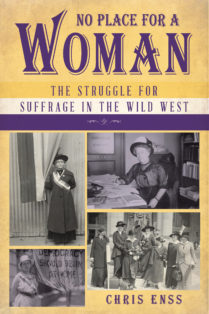

No Place for a Woman: The Fight for Suffrage in the Wild West.

Susan B. Anthony was born on February 15, 1820, in Massachusetts and began her work as a woman’s rights leader before the Civil War.

Possibly no woman ever lived who gave so many years of active work to a reformatory measure and so well retained her vitality as did Susan B. Anthony. Friends and acquaintances said she was a gentle woman who went up and down the country for two generations demanding that women be allowed to vote.

Anthony made her home in Rochester, New York. It was there she met many leading abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass, Parker Pillsbury, Wendell Phillips, William Henry Channing, and William Lloyd Garrison. Soon the temperance movement enlisted her sympathy and then, after meeting Amelia Bloomer and through her Elizabeth Cady Stanton, so did that of woman suffrage.

The rebuff of Anthony’s attempt to speak at a temperance meeting in Albany in 1852 prompted her to organize the Woman’s New York State Temperance Society, of which Stanton became president, and pushed Anthony further in the direction of women’s rights advocacy. In a short time she became known as one of the cause’s most zealous, serious advocates, a dogged and tireless worker whose personality contrasted sharply with that of her friend and coworker Stanton. She was also a prime target of public and newspaper abuse. While campaigning for a liberalization of New York’s laws regarding married women’s property rights, an end attained in 1860, Anthony served from 1856 as chief New York agent of Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society.

During the early phase of the Civil War, she helped organize the Women’s National Loyal League, which urged the case for emancipation. After the war she campaigned unsuccessfully to have the language of the Fourteenth Amendment altered to allow for woman as well as African American suffrage, and in 1866 she became corresponding secretary of the newly formed American Equal Rights Association. Her exhausting speaking and organizing tour of Kansas in 1867 failed to win passage of a state enfranchisement law.

In 1868 Anthony became publisher, and Stanton editor, of a new periodical, The Revolution, originally financed by the eccentric George Francis Train. The same year, she represented the Working Women’s Association of New York, which she had recently organized, at the National Labor Union convention. In January 1869 she organized a woman suffrage convention in Washington, D.C., and in May she and Stanton formed the NWSA. A portion of the organization deserted later in the year to join Lucy Stone’s more conservative AWSA, but the NWSA remained a large and powerful group, and Anthony continued to serve as its principal leader and spokeswoman.

In 1870 she relinquished her position at The Revolution and embarked on a series of lecture tours to pay off the paper’s accumulated debts. As a test of the legality of the suffrage provision of the Fourteenth Amendment, she cast a vote in the 1872 presidential election in Rochester, New York. She was arrested, convicted (the judge’s directed verdict of guilty had been written before the trial began), and fined, and although she refused to pay the fine, the case was carried no further. She traveled constantly, often with Stanton, in support of efforts in various states to win the franchise for women: California in 1871, Michigan in 1874, Colorado in 1877, and elsewhere.

In 1890, after lengthy discussions, the rival suffrage associations were merged into the NAWSA, and after Stanton resigned in 1892, Anthony became president. Her principal lieutenant in later years was Carrie Chapman Catt.

By the 1890s Anthony had largely outlived the abuse and sarcasm that had attended her early efforts, and she emerged as a national heroine. Her visits to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and to the Lewis and Clark Exposition in Portland, Oregon, in 1905 were warmly received, as were her trips to London in 1899 and Berlin in 1904 as head of the U.S. delegation to the International Council of Women (which she helped found in 1888). In 1900, at age eighty, she retired from the presidency of the NAWSA, passing it on to Catt. Anthony died in 1906, fourteen years before the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified.

To learn more about how women won the right to vote in the West read

No Place for a Woman

Visit www.chrisenss.com to enter to win a copy of No Place for a Woman.