Criticism and rejection are a part of a writer’s life. It’s certainly not the part most writers like, but as author Elbert Hubbard wrote “To escape criticism – do nothing, say nothing, be nothing.”

A few years ago, I wrote a book about the life of Elizabeth Bacon Custer, George Custer’s widow. The book is entitled None Wounded, None Missing, All Dead: The Story of Elizabeth Bacon Custer. She was a fascinating woman, an amazing writer, a gifted artist, and I wanted to tell her story. I was surprised by the critics who blasted me for not covering the Battle of Washita River or Custer’s Civil War career. The title clearly indicates the work is about Elizabeth Bacon Custer’s life, so I was a bit confused by the remarks.

I was confused, but not surprised. Over the years, I’ve had my fair share of poor reviews including one that read, “My family doesn’t care much for history. We like magic.”

If you’re a working writer, you’re going to face criticism and rejection. From the literary agent who isn’t interested in representing you, editors who don’t want your manuscript, publishers who give you an insulting advance, to the ultimate rejection and criticism – poor sales. The world is filled with critics. No one is immune, particularly those who are creative.

Authors, poets, songwriters, even inventors working on designing better faucets are subject to criticism. Okay, THAT guy is a moron. The faucets are fine, stop messing with the faucets, all right. The ones in airports are like science projects with electronic eyes and motion sensors that never work no matter how many times you wave your hand under the device. Hey faucet guy! Stop it!

I’m not saying there isn’t a place for solid, intelligent, constructive criticism, but when was the last time you read a review of a western novel or nonfiction work, song, poem, or western film that gave you a real feel of what the author was trying to say? Critics don’t always get it right either. In 1884, Mark Twain’s book The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn received the following review. “A gross trifling with every fine feeling…Mr. Clemens has no reliable sense of propriety.” A reviewer of Owen Wister’s work The Dragon of Wontley wasn’t shy with his criticism when he shared, “Wister’s story is a burlesque and grotesque piece of nonsense…it is mere fooling and does not have the bite and lasting quality of satire.” An editor reviewing one of Tony Hillerman’s manuscripts in 1970 noted “If you insist on rewriting this, get rid of all that Indian stuff.” After reading Zane Grey’s book The Last of the Plainsmen, an editor informed him, “I do not see anything in this to convince me you can write either narrative or fiction.” Another editor wrote the following about Grey’s book Riders of the Purple Sage, “It is offensive to broadminded people who do not believe that it is wise to criticize any one denomination or religious belief.” Even John Steinbeck was subject to critics who didn’t get it right as evidence in a review for his book Of Mice and Men that appeared in the May 1937 edition of Time Magazine. “An oxymoronic combination of the tough and tender, Of Mice and Men will appear to sentimental cynics, cynical sentimentalists…Readers less easily thrown off their trolley will still prefer Hans Anderson.”

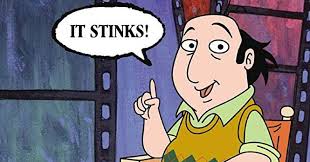

What danger is to a cop, rejection is to a writer – always hanging in the air dripping with possibility. And drip it does onto the talented and untalented in almost equal measure. Some days it’s hard to find the drive to keep writing when you consider your work might be ridiculed and or tossed aside but you have to power on. How you master this challenge will have a profound effect on your career. I once received a rejection letter that read, “Something stinks, and I think it’s this manuscript.” Did I let it stop me? No, I continued churning out stinky material…wait, that came out wrong.

Louis L’Amour admitted “I do not believe writers should read reviews of their own books, and I do not. If one is not careful one is soon writing to please reviewers and not their audience or themselves.” One of the keys to becoming a contented writer is to not let people’s compliments go to your head and to not let their criticism get to your heart. If you’re one of those writers who have mastered this idea, I’d love to hear from you. In the meantime, I’ll be at my desk rereading an Amazon review of my work which simply stated, “Maybe you should think about becoming a mime.”