Enter now to win a copy of

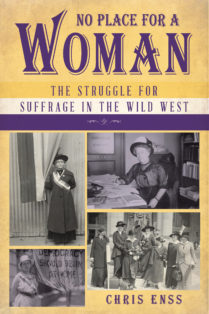

No Place for a Woman: The Struggle for Suffrage in the Wild West

It was a typical Colorado October evening, one of those days when a promising crisp and sunny morning had turned dark and windy by late afternoon. In spite of the rain and bluster, however, a crowd was gathering in the Union Hall on Pearl Street to hear the legendary Susan B. Anthony address the subject of woman suffrage. It was 1877, and the creation of Colorado’s one-year-old state constitution was still fresh in its citizen’s memories. And both women and men were asking the question: Why shouldn’t Colorado follow Wyoming and Utah’s example and extend universal suffrage to the so-called “fairer sex?”

Anthony was, by that time, a veteran of the fight for women’s rights in the United States, a former champion of the abolitionist movement, and a fierce proponent of the right to vote for all citizens. In 1872, after the ratification of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution, she and a group of her sisters and friends had registered to vote in Rochester, New York, arguing that the 14th amendment gave them that right. The women were then arrested for casting their ballots. Anthony was held on $1000 bail and was then fined $100 for casting her vote. And Anthony was only one of the many women who had been fighting since the 1840s to have their voices heard. Across the country, women had been agitating for the vote and making allies of men. And in the West, at least, it seemed that men were listening. In Utah and Wyoming, the writers of the territorial constitutions had recognized the political expediency of enfranchisement for women, and in Colorado, the topic was ripe for debate.

Scarcely a month before Colorado officially became a state on August 1, 1876, the citizens of Denver had gathered for a grand 4th of July celebration, an even that seemed especially significant in that centennial year. Parades and toasts included stirring words about the role of women in the state, and one speaker solemnly intoned, “May there yet be had a fuller recognition of her social influence, her legal identity and her political rights.” The pressure for the state to allow women the vote was growing.

In fact, as early as 1870, Territorial Governor Edward McCook had proposed the idea of following the example of Wyoming Territory and extending the full franchise to the women of Colorado. His efforts were rebuffed, but the notion had caught the attention of the men who were elected to take the state through the process of writing the constitution five years later. Delegates Henry P. Bromwell of Denver and Agipeto Vigil from Huerfano and Las Animas Counties proposed that equal suffrage be included in the state constitution, but were outvoted when the constitution came to a vote in 1876, limiting women’s right to vote to school elections.

The next year, however, a referendum on the issue went before the male voters of the state asking to grant the franchise to the women who worked and lived alongside them, and the historic move brought luminaries of the national suffrage movement to the Rocky Mountains. Henry Blackwell and Lucy Stone joined Susan B. Anthony in stumping across the state. Local suffragists such as Matilda Hindman and Margaret Campbell were joined by former territorial governor John Evans in encouraging their fellow Coloradans to vote yes on the measure that November.