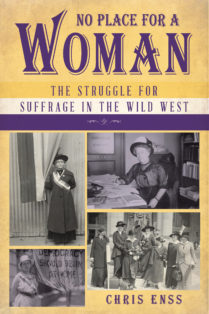

Enter now to win a copy of

No Place for a Woman: The Struggle for Suffrage in the Wild West.

Among the busy men sitting at rows of welding machines at the Standifer-Clarkson Shipyard in Vancouver, Washington, in 1917, were several equally busy women. All were dressed in drab gray or brown clothing, work boots, heavy, canvas aprons, and off-white, triangular scarves covered their heads. Sparks flew from the metal pieces being fused together to be used to build ships that would be dispatched to fight in the war in Europe. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary in June 1914 propelled the major European military powers toward war. Gavrilo Princip, a Yugoslav nationalist, was responsible for Ferdinand’s death. His actions prompted Austria-Hungary to declare war on Serbia. European nations aligned themselves with the side of the argument they favored and fighting ensued for more than three years before the United States entered the conflict. Germany’s atrocities during this time forced the United States to declare war on the country in April 1917. Hundreds of thousands of American men were enlisted to fight, leaving numerous vacancies in the work force. Women were recruited to fill those positions. Some of those positions were in shipyards such as the Standifer-Clarkson Shipyard.

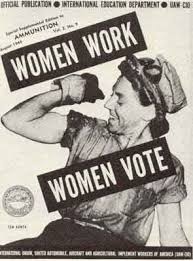

Despite the prevailing idea among traditionalists that women should stay out of the work force, World War I made the need for labor so urgent that women were hired in record numbers. In addition to taking jobs in department stores, railroads, and with the postal department, women answered the call to be employed as police officers, firefighters, munitions workers. By the spring of 1918, munitions factories were the largest employer of American women.

When it came to serving their country, women proved they were equal to men. The employment of women supported the war. Women worked not only as nurses but also as ambulance drivers, in steel mills, and in the textile industry. Women across the nation were doing their part to help. Although some political leaders recognized their contributions and were grateful, they still were not convinced granting women the vote was right for the country.

By the time the United States had entered World War I, all the western states had achieved women’s suffrage at some level, but securing the right for women to vote in every state continued to be a struggle. As a leader of the National Woman’s Party, Lucy Burns’ comments about that struggle were echoed by women everywhere. “It’s unthinkable that a national government which represents women should ignore the issue of the right of all women to be politically free,” Lucy noted. Regardless of the battle being fought abroad, key suffragist leaders such as Harriot Stanton Blatch, (daughter Elizabeth Cady Stanton), Alice Paul, and Lucy Burns believed women needed to continue to fight for their rights on the home front.