Enter now to win a copy of

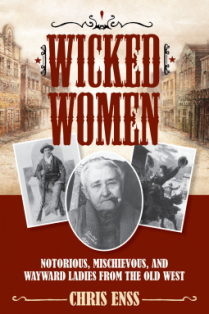

Wicked Women:

Notorious, Mischievous, and Wayward Women of the Old West

In 1849, women of easy virtue found wicked lives west of the Mississippi when they followed fortune hunters seeking gold and land in an unsettled territory. Prostitutes and female gamblers hoped to capitalize on the vices of the intrepid pioneers.

More than half of the working women in the California during the 1850s were prostitutes. At that time, madams – those women who owned, managed, and maintained brothels – were generally the only women out west who appeared to be in control of their own destinies. For that reason alone, the prospect of a career in the “oldest profession” – at least at the outset – must have seemed promising.

Often referred to as “sporting women” and soiled doves,” prostitutes mostly ranged in age from seventeen to twenty-five, although girls as young as fourteen were sometimes hired. Women over twenty-eight years of age were generally considered too old to be prostitutes.

Rarely, if ever, did working women use their real names. In order to avoid trouble with the law as they traveled from town to town, and to protect their true identities, many of these women adopted colorful new handles like Contrary Mary, Little Gold Dollar, Lazy Kate, and Honolulu Nell. The vicinities where their businesses were located were also given distinctive names. Bordellos and parlor houses typically thrived in that part of the city known as “the half world,” “the badlands,” “the tenderloin,” “the twilight zone,” or the red-light district.”

The term “red-light district” originated in Kansas. As a way of discouraging would-be intruders and brazen railroad workers around Dodge City began hanging their red brakemen’s lanterns outside their doors as signal that they were in the company of a lady of the evening. The colorful custom was quickly adopted by many ladies and their madams.

Generally speaking, a prostitute’s class was determined by her location and her clientele. High-priced prostitutes plied their trade in parlor houses. These immense, beautiful homes were well furnished and lavishly decorated. The women who worked at such posh houses were impeccably dressed, pampered by personal maids, and protected by the ambitious madams who managed the business. In general, parlor houses were very profitable. Madams kept repeat customers interested by importing women from France, Russia, England, and the East Coast of the United States. These ladies could earn more than $25 a night. The madams received a substantial portion of the proceeds, which were often used to improve the parlor house or to purchase similar houses.

The lifestyle was, without a doubt, a dangerous one, and many women despised being a part of the underworld profession. As Nebraska madam and prostitute Josie Washburn noted in 1896: “We are there because we must have bread. The man is there because he must have pleasure; he has no other necessity for being there; true if we were not there the men would not come. But we are not permitted to be anywhere else.”

Entertaining numerous men often resulted in assault, unwanted pregnancies, venereal disease, and even death. Some prostitutes escaped the hell of the trade by committing suicide. Some drank themselves to death; others overdosed on laudanum. Botched abortions, syphilis, and other diseases claimed many of their lives as well.

In the late 1860s, a concern for the physical condition of prostitutes – and moreover, for the effect their poor health was having on the community at large – was finally addressed. Government officials, alerted to the spread of infectious illnesses, decided to take action against women of ill repute. At a public meeting in New York City, a bill was introduced that was aimed at curtailing the activities of prostitutes who did not pass health exams. The goal of the bill was to stop the advance of what morally upright citizens termed the “social evil.”