1870 – Ester Hobart Morris is appointed Justice of the Peace in South Pass, Wyoming. She’s the first female JOP in the Old Wes.

Becoming Citizens: Woman Suffrage in California

Enter now to win a copy of the new book

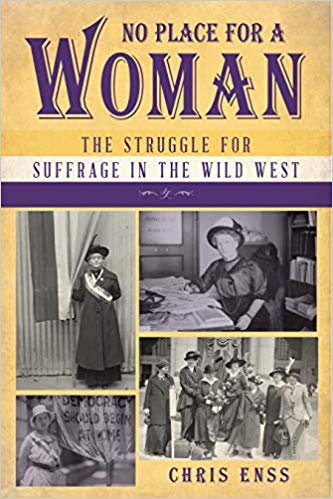

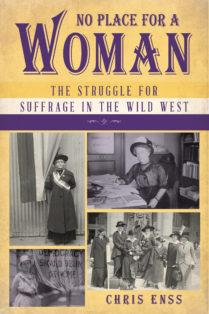

No Place for a Woman: The Fight for Suffrage in the Wild West.

When suffragist Susan B. Anthony boarded the passenger car of the Union Pacific Railroad in Ogden, Utah, in late December 1871, the train was filled to capacity. Men, women, children, livestock, baggage, and crates containing food and supplies were being loaded onto the vehicle bound for Chicago. Weary and carrying an oversized satchel bulging with clothing, books, and papers, the fifty-one-year-old woman climbed aboard and began the slow procession past the throngs of people occupying various seats and berths. She snaked her way toward the semi-private compartments until she found the one she was to occupy for the duration of the trip. The pair Anthony would be traveling East with had already arrived and made themselves comfortable. She smiled at the congenial-looking couple as she entered. California congressman Aaron A. Sargent politely got to his feet to help her stow away her bag. He introduced himself, then introduced his accomplished wife, Ellen, to Anthony, who returned the kindness.

Not long after Anthony was settled, Ellen admitted to being familiar with her work. Anthony’s crusade to acquire the right to vote for women had been covered in the Sacramento newspapers as well as the publications in Nevada City, California, where the politician and his family lived. She had joined the fight for woman’s suffrage in 1852. Since that time, she had traveled from town to town, inspiring women to fight for equal rights. The crusade, which initially began in Seneca Falls in New York in 1840, had expanded westward. Once Wyoming granted women the privilege to cast their ballots, suffrage rose up in territories beyond the Mississippi to battle for the opportunity to do the same. Crusaders reasoned if women could gain that right state by state the federal government would be persuaded to pass an amendment making it law.

From June to December of 1871, Anthony had traveled more than thirteen thousand miles, delivered 108 lectures, and attended close to two hundred rallies on the issue of woman’s suffrage. There were others such as Emily Pitts Stevens, who helped form the California Woman Suffrage Association, and physician and minister Anna Howard Shaw who had joined the fight and were hosting meetings to inform and educate women about the movement. It was essential that the message of equality be heard in every mining community, fishing village, and major city from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Women needed to be encouraged to petition for enfranchisement. They needed to be reminded they were entitled to speak for themselves and stand against fathers and husbands voting for them. Anthony and the other dedicated suffragists had been able to share the message with women in Kansas, Wyoming, Utah, Washington, and Oregon; they had great hope the ladies in California would back reform.

Anthony couldn’t have found a more receptive audience for her message than Congressman Sargent and his wife. Ellen had founded the first suffrage group in Nevada City, California, in 1869, and Aaron was in full support of giving women the vote. The Sargents had moved to California from Massachusetts in 1849 and settled in Nevada City in 1850. In addition to owning and operating the newspaper the Nevada Daily Journal, Aaron was an attorney and former U. S. senator. Ellen was a homemaker and mother who was active in the Methodist Church. She firmly believed that women could not attain their highest development until they “had the same large opportunities and the same large chances as her brothers have.”

To learn more about how women won the right to vote in the West read

No Place for a Woman

This Day…

1870 – Utah becomes the second territory in the United States to pass a law allowing women the vote, after Wyoming in 1869.

Ester Hobart Morris & Woman Suffrage in Wyoming

Enter now to win a copy of the new book

No Place for a Woman: The Fight for Suffrage in the Wild West.

Esther Hobart Morris carefully arranged borrowed chairs and warmed, borrowed teacups as she prepared for her visitors to arrive. Her tiny mountain cabin, perched at seventy-five hundred feet of elevation in the mountains at South Pass City, Wyoming Territory, was cleaned, decorated, and full of all of the delectable morsels she could contrive for the important guests who would be arriving soon. Her husband, Jim Morris, was barely tolerant of the bustle as he nursed a foot swollen with gout, but he didn’t make his objections audible. The couple had only been in South Pass City a few months, and the time had not been easy for him, though Esther had leapt into local life with her usual enthusiasm. Her son from her first marriage, Archibald Slack, was soon to arrive to report on the afternoon’s event for the newspaper. His story would appear in time for the elections that were to be held the next day in the boomtown of two thousand men, women, and children. White men would be voting to send delegates to Wyoming’s Territorial Convention.

Everything about the scene Esther set that day in her tiny home was right by her standards and the standards of the day. The room was cozily domestic, and any Victorian in 1869 would have felt at ease with the ritual that was about to take place. The pouring of tea by a proper wife and mother, the gathering of friends over small plates of sandwiches and desserts, removed gently from cherished china with delicate tongs, the feathers and frills worn by the women and the ridges from hats just removed remaining in the hair of the gentlemen were both comforting and comfortable. But the gentle talk of community events and shared acquaintance of an elegant tea would give way to the talk that was dominating South Pass City on that fall day—the territorial elections of the next day and the future of Wyoming Territory itself. And that was exactly what Esther Morris intended.

To learn more about how women won the right to vote in the West read

No Place for a Woman

No Place for a Woman

In 1869, more than twenty years after Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony made their declaration of the rights of women at Seneca Falls, New York, the men of the Wyoming Territorial Legislature granted women over the age of 21 the right to vote in general elections. And on September 6, 1870, a grandmother named Louisa Ann Swain stepped up to a ballot box in Laramie, Wyoming, and became the first woman in the United States to exercise that right, ushering in the era of Western states’ early foray into suffrage equality. Wyoming Territory’s motives for extending the vote to women might have had more to do with publicity and attracting female settlers than with any desire to establish a more egalitarian society. However, individual men’s interests in the idea of women’s rights had their roots in diverse ideologies, and the women who agitated for those rights were equally diverse in their attitudes.

No Place for a Woman: The Struggle for Suffrage in the Wild West by Chris Enss and Erin Turner, explores the history of the fight for women’s rights in the West, examining the conditions that prevailed during the vast migration of pioneers looking for free land and opportunity on the frontier, the politics of the emerging Western territories at the end of the Civil War, and the changing social and economic conditions of the country recovering from war and on the brink of the Gilded Age. The stories of the women who helped settle the West and who ushered in voting rights decades ahead of the 19th Amendment and the stories of the country they were forging in the West will be of great interest to readers as the 100th anniversary of national woman suffrage approaches and is relevant in our current political climate. Through the individual stories of women like Esther Hobart Morris, Martha Cannon, and Jeannette Rankin, this book fills a hole in the story of the West, revealing the real story of how the hard work and individual lobbying of a few heroines, plus a little bit of publicity-seeking and opportunism by promoters of the Wyoming Territory, ushered in a new era for the expansion of women’s rights.

This Day…

1942 – Glenn Miller awarded 1st ever gold record for selling 1 million copies of “Chattanooga Choo Choo”

First the West, Then The Rest of the Nation

Enter now to win a copy of the new book

No Place for a Woman: The Fight for Suffrage in the Wild West.

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.

Margaret Mead

July 9, 1848, Waterloo, New York. It was a hot Sunday afternoon, and Jane Hunt, wife to prominent Quaker Richard P. Hunt, was home tending her two-week-old daughter and awaiting the arrival of the guests she expected for afternoon tea. Hunt’s home, an elegant, federal-style mansion, was comfortable and well-appointed, though not overtly luxurious, as befit her Quaker faith. It was the perfect venue for a meeting between a group of local Quaker women and renowned speaker, minister, and champion of reform Lucretia Mott, who was in the area visiting from Philadelphia. Mott, a Quaker minister, had been speaking openly in public and advocating fiercely for the abolition of slavery since the 1830s.

Hunt likely looked forward to the tea party and to the lively discussion she expected with Mott; her friend and fellow Quaker Mary Ann McClintock; Mott’s sister, Martha Wright; and an acquaintance of Mott’s named Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Mary Ann McClintock was the wife of the local Quaker minister—both she and he were adherents to a branch of Quakerism called Hicksites, which promoted equality between the sexes. Martha Wright was well known for her intellect, her witty commentary, and for her support of her sister’s work and beliefs. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who had first met Mott when the two were excluded from participation in the 1840 World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London on the basis of their sex, was also in attendance as she was visiting from nearby Seneca Falls, New York. Stanton took the opportunity, while the women enjoyed tea and dainty treats in Hunt’s spacious and comfortable parlor, to unleash “a torrent of [her] long-accumulating discontent,” over the inequality of the sexes.

To learn more about how women won the right to vote in the West read

No Place for a Woman

No Place for a Woman Has Arrived

This Week in History

End of the Trail

Last Chance to enter to win a copy of

Thunder Over the Prairie:

The Story of a Murder and a Manhunt by the

Greatest Posse of All Time

A fresh mound of earth covered Dora Hand’s grave and a sweet breeze danced around the crudely fashioned marker stuck in the dirt where she had been buried. Several bouquets of wilted flowers encircled the wooden tombstone. Although their blooms had faded somewhat, they represented the only color in the soap weed infested cemetery. For a short time after James Kenedy’s acquittal in December 1878, mourners returned to Dora’s plot to deposit fresh flowers, remember the entertainer and reflect on the shooting that took her life.

The news of what James had done and the posse that pursued him followed the cattleman to Texas, and he reveled in the notoriety. Youth often wobbles dangerously, then steadies to follow the straight and narrow path, but not in his case. The injuries he sustained during his capture had left him a cripple, and he was anxious to prove that the disability had not affected his gunplay.

He learned to use his left arm to draw his weapon and rumors prevailed that he killed several men with his quick hand during a brief stay in Colorado in November 1880.

By 1882, James had settled down and married the daughter of a wealthy landowner. He focused on the family business and worked closely with his father, earning the man’s respect and confidence. Neighbors and acquaintances considered James to be a “man of industry with good business qualifications and a trusted manager of Mifflin’s large ranch and cattle business.”

James Kenedy died on December 29, 1884 of tuberculosis, shortly after his son, George Mifflin was born. News of his death was slow to reach Dodge City, but well received. Mayor Kelley was particularly pleased. He had taken the death of Dora Hand hard. His emotional attachment to her, combined with the fact that a bullet intended for him had killed her, had left him devastated. Like many Dodge City residents who had been fond of Dora, Mayor Kelley felt “the only punishment meted out to James had been the sickness he endured from being shot by the posse.” After James was apprehended, Mayor Kelley expected the gunslinger to be found guilty of murdering the songstress and subsequently hung. The mayor was disappointed with the judge’s ruling to acquit.

Mayor Kelley served four terms in office, stepping down from the position in March 1881. He left the job after being accused by his business partner of allowing a customer to pass a counterfeit dollar to him. In spite of the embarrassing incident, residents viewed him as an effective town leader. He helped pass ordinances outlawing houses of ill repute, increased licenses for taverns to help provide services to the community and organized a law enforcement team that eventually became known throughout the territory as the “toughest group of men in the west.”

With the exception of his daughter, Irene, there was no other significant woman in Mayor Kelley’s life. He consorted with very few ladies in public after the loss of Dora and focused much of his attention on his purebred greyhound dogs. In November 1885 a fire burned one of Mayor Kelley’s saloons to the ground. He rebuilt the saloon, but never fully recovered financially and was eventually forced to sell all of his real estate holdings to sustain himself. When his health began to fail in late 1910, he moved to the Soldier’s Home at Fort Dodge.