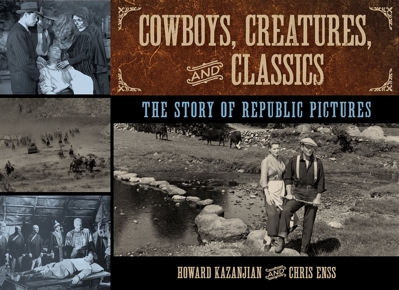

Enter now to win a copy of

Cowboys, Creatures and Classics: The Story of Republic Pictures

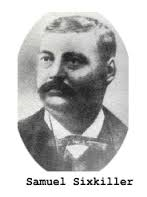

Herbert Yates, a tall, compact man in his mid-fifties, stood staring out the window of his magnificent office at Republic Pictures in Studio City, California, surveying the domain spread before him. A scene from a western film was being rehearsed in the middle distance. The usual, turbulent activity surrounded it: extras, makeup women, cameramen, grips, assistants, set designers, etc. Yates lit a cigar the size of a baby’s leg and held it tightly in his teeth. He took a long puff and blew the smoke out the corner of his mouth and checked the pockets of his charcoal gray, Brooks Brothers suit for the additional cigars he had tucked away. He patted them reassuringly, then rolled the fat stogie from one side of his mouth to the other.

Yates had acquired his taste for cigars while working as a salesman at the American Tobacco Company. Paired with a stiff bow tie, a receding hairline, and a dour expression, the cigar added a layer of seriousness to his persona. As head of a burgeoning, motion picture studio, he felt the look was necessary. He wanted to appear menacing. More often than not, his business approach was “never underestimate the power of good, old-fashioned intimidation.”

Herbert Yates founded Republic Pictures in 1935, but his history working in the movie industry began twenty years prior to the creation of the studio. Yates’ introduction to cinema came by way of a film-processing business called Hedwig Laboratories. He learned all about developing celluloid and relationships with some of the most profitable filmmaking executives in the field. He parlayed his knowledge into his own processing venture called Consolidated Film Industries. In a short time, Consolidated Film Industries became the leading laboratory in southern California. They processed negatives and made prints for the majority of movies produced by studios such as First National Pictures, Warner Bros., and Fox Film Corporation. Consolidated Film Industries proved to be extremely profitable for Yates, and he sought other areas of the industry of which to be a part. He acquired record companies and financed ventures for director Mack Sennett and comedic actor Fatty Arbuckle.

Within eight weeks of advancing funds to Sennett and Arbuckle, Yates received a 100 percent return on his investment. The speed in which his funds were replenished intrigued him. Yates saw the profit to be made in producing motion pictures, and it whetted his appetite for further opportunities.

To learn more about the many films Republic Pictures produced read

Cowboys, Creatures and Classics: The Story of Republic Pictures