1863 Assault of Battery Wagner and death of Robert Gould Shaw.

Defending a Nation

Enter to win a copy of

Sam Sixkiller: Frontier Cherokee Lawman

Everyone who enters WINS.

A springboard wagon topped a ridge surrounded by a grove of ancient juniper trees seven miles outside Muskogee. The wagon was weighted down with several heavy crates and made little sound. The contents inside the crates sloshed as the vehicle slogged through the rain-soaked turf. The soft ground muffled the hardworking wheels and the horses’ hooves. Solomon Coppell, an unshaven man dressed in a dirty, fawn-colored suit with a long-tailed coat, drove the wagon over a crude trail cut deep in mud and dirt. His roving button eyes scanned the scene in front of him, looking for anything out of the ordinary.

Just beyond Solomon’s line of sight, tucked behind a thicket of brush, Captain Sam Sixkiller sat on his horse watching the driver. Sweat rolled down the lawman’s face that late spring day in 1883 as the sun rode up into a leaden sky, empty and cloudless, and blanketed the captain with a sticky heat. Solomon was uncomfortable too. He pulled his flat-brimmed hat off his head, backhanded a bead of perspiration off his hairline, reset his hat, and fixed his gaze back on the muddy track. The captain waited for just the right moment, and in one fast, flawless movement spurred his horse onto the trail directly in front of Solomon’s team.

A stunned Solomon quickly jerked back on the reins of the animals, bringing the skittish horses to a stop. “Hold it, Coppell!” Captain Sixkiller announced in a sober, stern voice. “You’re under arrest.” Solomon glanced at the cargo he was hauling and back to the captain. The lawman was alone and the bootlegger was confident he could survive a confrontation with his wagonload intact. Solomon stared at the captain for a moment, then shook his head. “I got a tip you were bringing booze into the Nation,” the captain informed him. Solomon didn’t reply and showed no signs of cooperating. “Surrender, Coppell,” Captain Sixkiller warned him again. “Throw your guns out in the road.”

The captain was empty-handed, his leg gun still resting in a holster on his thigh. Coppell made a grab for the shotgun on the wagon seat. Sixkiller’s hand whipped forward in a short, small arc. There was no strain. He saw Coppell’s face, distorted and desperate. His gun kicked back against his wrist. One shot. Captain Sixkiller’s gun exploded before it cleared his coat. The flame of the lawman’s shot licked through the fabric and curled to form a smoldering ring. He watched Coppell’s body jerk. Coppell swayed and fell into the trace chains and wagon tongue. The team reared and snorted and pawed at the air. The captain calmed the horses and kept them from running away.

Most Muskogee residents agreed that Captain Sixkiller was an effective policeman, quick to enforce the laws regarding the buying and selling of liquor. Nevertheless, some thought the rules should be relaxed. Cherokee Indian business owners believed they should have the right to purchase liquor to sell to white railroad workers and settlers passing through. Indian leaders maintained that such measures would lead to an increase in violence on the Cherokee Nation and insisted that troublemakers who peddled whiskey needed to be stopped.

Although Captain Sixkiller was never accused of being too harsh on those who violated the law, some Indians, including former chief of the Cherokee Nation, Lewis Downing, and Indian agent John B. Jones, thought that the US marshal and his deputies went too far in upholding the law. “Some deputy marshals make forcible arrests,” Chief Downing told Indian agent Jones in a letter, “without regard to circumstances or the facts of the case, and without any of the forms of law.” Smugglers occasionally planted whiskey on innocent people traveling through the Cherokee Nation. If they were stopped by Captain Sixkiller or his deputies and alcohol was found in their possession, they were arrested and taken immediately to Fort Smith, Arkansas, to be prosecuted. Chief Downing strenuously objected to the captain’s rush to judgment, arguing that in those instances, such individuals should be given the benefit of the doubt.

To learn more about Sam Sixkiller read:

Sam Sixkiller: Frontier Cherokee Lawman.

This Day…

Mayhem in Muskogee

Enter to win a copy of

Sam Sixkiller: Frontier Cherokee Lawman

A hot sun beat down on the busy residents of Muskogee, Oklahoma Territory, in June 1880. A heavy veil of humidity, like a stifling blanket, hung over the town as well. Situated nearly thirty miles southwest of Tahlequah, the primitive railroad stop was slowly coming into its own. More than five hundred people called the area home, and many among them were employees of the Missouri Pacific Railroad. At the end of the day, workers gathered by the score and milled about the hamlet of lean-tos, tents, and cabins. Gamblers had pitched their canvas dwellings in prime spots, and crowds flocked around their tables.

Quarrels frequently flared up between slick poker dealers and inexperienced card players. Soiled doves (prostitutes) prowled around the gaming tents and curious male bystanders like panthers. They enticed men to their crude rooms, then stripped them of any funds they had not already lost in a crooked card game. Unsuspecting shoppers and their families roamed in and out of the heated arguments that spilled into the street, gawking warily at the chaos while on their way to and from various stores.

City officials watched the scene play out in disgust. Bootleg alcohol was usually sold to the railroad crews and the houses of ill repute, and the clientele had a hard time controlling the amount they consumed. More often than not, customers who frequented bawdy houses and who drank to excess were prone to violence. They terrorized the neighborhood surrounding the brothels, recklessly firing their guns at women and children and brawling with townsmen who challenged them to put away their weapons.

In spite of repeat warnings from law enforcement officers like Colonel J. Q. Tuffts, a US agent for the Union Indian Agency in Muskogee, the madams who ran the brothels refused to voluntarily shut down their businesses. Brothels were considered a necessary evil; after all, a portion of the income spent at these houses supported public services such as the police department. Nevertheless, Agent Tuffts considered the bordellos a plague on the town, nothing more than a refuge for criminals and delinquents from miles around. When Agent Tuffts made Sheriff Sixkiller captain of the Indian Police in early February 1880, he made ridding Muskogee of such houses a priority for Sam’s administration.

To learn more about Sam Sixkiller read:

Sam Sixkiller: Frontier Cherokee Lawman.

This Day…

This Day…

Trouble in Tahlequah

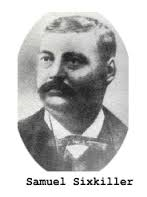

Enter now to win a copy of

Sam Sixkiller: Frontier Cherokee Lawman

Willis Pettit, a tall, well-built black man, sunk his spurs into his horse’s back end and the animal, already moving at a fast pace, quickened its stride. The anxious rider chanced a glance over his shoulder to see if he was being followed. In the rapidly disappearing landscape there was no sign of any other rider. A flash of relief passed over his face.

Sheriff Sam Sixkiller, who was in pursuit of Pettit and had anticipated the route the fleeing criminal would take, waited for him at a ford in the Illinois River several miles outside of Tahlequah. The sheriff’s horse carried him over the rocks through a shallow section of water, then dropped its head to the surface and eagerly drank. Sam swung himself crossways in the saddle, lifted the canteen hanging off the horn, opened the container, and took a long swig. He carefully scanned the scenery around him as he hopped off his horse and plunged his canteen into the water to refill it. The sound of a fast-approaching horse made him pause for a moment. The sheriff returned the canteen to his saddle, then lifted his rifle out of its holster. Turning slowly toward the sound, he leveled his gun in the direction of the oncoming steed.

Pettit and his ride emerged from the thicket that flanked the river on both sides and followed the incline to the water’s edge. The horse spooked and reared back when it came upon Sheriff Sixkiller, and Pettit was thrown to the ground. Before he could even get to his feet, he was staring down the barrel of the sheriff’s gun. He raised his hands in surrender, cursing his luck in the process.

On May 15, 1876, Sheriff Sixkiller arrested Willis Pettit for “assault with intent to kill Emanuel Spencer with a pistol.” It was the first of many arrests for Pettit in the Cherokee Nation during Sam’s time in office. Pettit, a former slave, aligned himself with other ex-slaves who believed they were entitled to a section of the territory that had been given to the Five Civilized Tribes. They argued that, as restitution, slaves owned by the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole tribes who were freed after the Civil War should be granted a part of the region for their own exclusive use. With the exception of the Seminole Indians, every tribe disagreed with the idea, and the conflict sparked controversy and, at times, violence.

To learn more about this courageous lawman read

Sam Sixkiller: Frontier Cherokee Lawman.

This Day…

1846 U.S. takes San Francisco .

Principles of Peace

Enter to win a copy of

Sam Sixkiller: Frontier Cherokee Lawman

The sweeping prairie lay quietly under the heat of a brassy sun as a lone wagon topped a grassy knoll that afforded an arresting view from every direction. Redbird Sixkiller drove the team of two horses pulling the wagon toward the town of Tahlequah, Oklahoma Territory, in the near distance. His four-year-old son, Sam, sat beside him captivated by the sights and listening intently to the stories Redbird told about his ancestors and the origin of the Sixkiller family name. Redbird shared with Sam a tale about one of their fearless relatives. The ancestor was engaged in battle against the Creek Indians and had killed six braves and then himself before another band of hostile Creek Indians that surrounded him could attack. The Cherokee Indian warriors who witnessed the daring act referred to the warrior as Sixkiller.

Given the courageous example Sixkiller had set, Redbird felt he owed it to the legendary Cherokee to face with the same fortitude the trials that lay ahead for the Indian Nation. It was a pathetic group of thousands of Indians who were herded west during the winter of 1838–39. Redbird Sixkiller’s recollection of the grueling journey that came to be known as the Trail of Tears was passed along to his son, his son’s sons, and every generation that followed. The January 18, 1972, edition of the Statesville, North Carolina, newspaper, the Statesville Daily Record, published Redbird’s reminiscences as told by those generations and noted that the inhumanity of the forced move of the Indians preyed on his sense of justice. He saw helpless Cherokee arrested, dragged from their homes, and driven at bayonet point into the stockades. He watched as his people were loaded like cattle into wagons and hauled west. Redbird told Sam how few of the Indians were given time to make arrangements to leave and that one family was driven from its home as members were preparing to bury a child who had died. He recounted how another mother forced from her home fell and died of a heart attack before they could take her to the stockade. Still another mother died of pneumonia contracted after giving her only blanket for the protection of a sick child.

Sam listened intently to his father describe a Cherokee elder’s reaction to the tragic event. The elder’s name was Chief Junaluska. During the Battle of the Horse Shoe, the chief saved the life of a man who would eventually become the president of the United States, and who would support the relocation of Indian tribes. The chief later admitted that if he had known the life he was saving was that of Andrew Jackson, American history would have been written differently.

Like many other Indians who survived the Trail of Tears, Redbird passed on to his son the stories of how government soldiers treated the Cherokee during this time. Only a few men were remembered for being humane. The majority of officers and the members of their units treated the Indians harshly. A soldier with the Georgia volunteers who showed sympathy to the Cherokee described in his memoirs the severity of the treatment the Indians received. “I fought through the War Between the States,” the veteran recounted, “and I have seen men shot to pieces by the thousands, but the Cherokee removal was the cruelest work I ever knew.”

To learn more about Sam Sixkiller read:

Sam Sixkiller: Frontier Cherokee Lawman.