Enter now for a chance to win the book

High Country Women: Pioneers of Yosemite National Park

Celebrate the 126th anniversary of Yosemite!

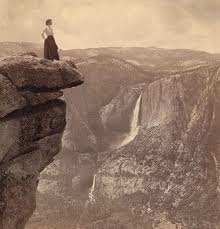

The light from a spectacular full moon spilled into the windows of the parlor at the Strentzel Ranch near the town of Martinez in the Alhambra Valley in California. The room was filled to overflowing with well-dressed guests, owners and operators of farms in the area and their wives and family. All eyes were on Louisa “Louie” Wanda Strentzel, a petite, thirty-one-year-old woman playing a piano. No one spoke as the melancholy tune she offered filled the air. Louie played well and had a voice to match the exceptional talent demonstrated. Midway through the mesmerizing performance, forty-year- old John Muir, an explorer and naturalist from Wisconsin, quietly entered the home and stood in the shadow of the door leading into the parlor. With the exception of a quiet greeting from Strentzel family friend Mrs. Jeanne Carr, his presence went largely unnoticed.1

John’s eyes were transfixed on Louie. She had high cheek bones, a firm mouth, and clear, gray eyes. He gazed at her with an unfathomable look of admiration and longing. At the conclusion of her song the gathering enthusiastically applauded. John followed suit as he ventured into the light. It was June 1, 1878.2

This was not the first time he had seen Louie. The two had been introduced in 1874 in Oakland at a meeting of homesteaders and farmers organized by her father, horticulturist Dr. John Strentzel. John and Louie had many friends in common, and many agreed they would make the perfect couple. Jeanne Carr had tried in vain to arrange a date between John and Louie, but John always had travel plans that conflicted with a rendezvous. In April 1875 Jeanne sent Louie a message letting her known that the “chronic wanderer,” as John was often referred to, could not be distracted from an expedition to the Cascade Range in Siskiyou County, California. “You see how I am snubbed in trying to get John Muir to accompany me to your house this week,” Jeanne wrote Louie. “Mount Shasta was in opposition and easily worth the choice.” Jeanne would not be defeated, however. She was convinced the two had so much in common their paths were bound to pass eventually and forever.3

Louie Strentzel was born in Texas in 1847. She was an only child and according to Louie and John’s daughter, Helen, “she was a devoted daughter and a great comfort to her parents in their later years.” Her father, a Polish physician who fled to American in 1840 to escape being drafted into the Russian Army, settled in the southwest near the city now known as Dallas. In 1849, he left Texas for California. Strentzel moved his wife and child to the Alhambra Valley north of Oakland. He purchased several hundred acres of land and began educating himself on how to grow various crops. According to the May 5, 1974, edition of the Joplin, Missouri, newspaper the Joplin Grove, the main product at the Strentzel farm was peaches.4

Louie inherited her father’s love of plants and flowers. In addition to her affection for growing things, she was interested in astronomy, poetry, and music. She was extremely bright and excelled at her studies at Miss Adkins’ Young Ladies Seminary in Benicia. Louie became a music scholar while in attendance at the seminary, and her teachers boasted that she had a bright future ahead of her as a concert pianist if she so chose. Once she graduated in 1864 she decided to return home to the ranch in Martinez and focus on fruit ranching and hybridizing.5

The stunning and talented Louie was not only the pride of the family, but according to the January 5, 1975, edition of the Long Beach, California, newspaper the Independent Press Telegram, “she was known widely for the grace with which she dispensed the generous hospitality of the Strentzel household.”6

John Muir was a frequent guest at the Strentzel homestead. He enjoyed conversing with Dr. Strentzel about his trek from Texas to California. Strentzel had been the medical advisor for a wagon train of pioneers called the Clarkesville train. He kept a journal of his travels and happily shared the experience with John. The Spanish name for the Alhambra Valley where the Strentzel’s settled was “Canada de la Hombre.” The English translation being Valley of Hunger.

To learn more about Louisa Strentzel Muir

and the other women who helped make Yosemite a National Park read

High Country Women: Pioneers of Yosemite National Park