1851 – Morgan Earp is born in Pella, Iowa.

Calamity Jane – Mysterious Marvel

Be a winner. Enter to win a copy of the new book

Soldier, Sister, Scout, Spy:

Women Soldiers and Patriots of the Western Frontier.

Cold rain lashed the huddle of tents staked just outside the rough encampment at Rapid City. Wind howled across the Dakota Territory as though driven by the devil himself, rattling the dripping canvas and blowing crude shakes from the leaky roofs of the buildings. Struggling through the mud, a young woman leaned into the gale and cursed. The stupidity of setting up a camp for sick soldiers on the lowest ground near General Crook’s encampment was enough to make a deacon swear, thought Martha Jane Canary.

The wind tore the tent flap from her grasp. Cursing again, she grabbed the wet canvas and yanked it into place. A lantern swaying from a hook on the tent pole cast meager light on the three men huddled in damp bedrolls. Martha Jane bent down to examine their scruffy faces, looking for the flush of fever, the outbreak of pustules, or the gray stillness of death.

Martha Jane knew the risk of close contact with these particular sick men. Settlers and soldiers moving onto the northern plains in 1876 still talked about the terrible smallpox epidemic of 1837. At the first sign of fevers or red lesions, victims were isolated because the contagion spread so quickly—and so fatally. It had literally wiped out whole tribes of Native Americans and killed thousands of fur traders, prospectors, and settlers.

The Indians called it “Rotting Face” because that’s exactly what it looked like. Fevers as high as 106 degrees, terrible back pain, a vicious headache that hammered with each heartbeat, chills, nausea, and convulsions marked the onset of the disease. Four days into the illness, the flat, red lesions appeared; then they puffed up and became clear blisters filled with pus that sometimes merged into one gigantic, painful mass.

Smallpox victims were unable to care for themselves and were often dumped into “pest houses” to prevent the spread of the sickness. Twenty-four-year-old Martha Jane Canary knew the symptoms and the fate of those who came into contact with the disease. Yet, she’d volunteered to nurse those in the leaky tents set up outside the town.

She breathed a sigh of relief after studying her patients. None of the men she examined in the cold, damp tent showed those terrifying symptoms. “Hell and Hallelujah,” she muttered. One by one, faces turned toward her voice, and crusted, red-rimmed eyes opened. “You boys look worse than grizzly bears with the mange,” she cracked. Gesturing toward the covered bucket she’d lugged down from town, Jane announced, “I got venison stew in the bucket.”

“You cook it?” asked one man as he struggled up on an elbow. He cast a doubtful glance at the pail.

“Hell, no. But I shot the damn deer just so you don’t have to eat no more of that mush you was whinin’ about.” The fierce frown gave way to a grin. “You boys need to build up your strength. I haven’t had a drink or a game since the fever hit, and I’m getting mighty restless.”

The men grinned in sympathy. They knew their nurse quite well.

To learn more about Calamity Jane and other such patriots read

Soldier, Sister, Scout, Spy:

Women Patriots and Soldiers on the Western Frontier.

This Day…

Juliet Fish Nichols – Lighthouse Keeper

Winning is easy. Enter to win a copy of the new book

Soldier, Sister, Scout, Spy:

Women Soldiers and Patriots of the Western Frontier.

Thick, damp, and cold fog pressed against the windows of the small house at Point Knox, condensed in a muted bronze gleam on the huge bell, slipped clammy fingers inside the cloak of the woman shivering on the small platform. Waves splashed and foamed against the rocks far below the wet planks where Juliet Fish Nichols listened tensely for the creak of rigging or the dull thunder of a steamship’s engine. She hoped she heard something before she saw it because any ship close enough to see was doomed.

Automatically, her throbbing arm lifted, and she rapped the small hammer twice against the side of the three-thousand-pound bell. Fifteen seconds later, she struck the bell again. Then, after counting off another fifteen seconds, she elevated the hammer and banged twice more on the great bell. Again and again, eight times each minute, Juliet lifted her aching arm and rang the bell, warning ships away from Angel Island in fogbound San Francisco Bay.

At least four ships were due in port that first week of July 1906: the Capac, City of Topeka, and Sea Foam, all of which plied the California coast, as well as the transpacific steamer Mongolia loaded with passengers from the Far East. Unfortunately, the crystal-clear atmosphere of July 1 had deteriorated rapidly in the following few days. Visibility was often no more than a few yards. Impenetrable fog concealed every landmark.

Juliet had seen the annual summer phenomenon many times, but this year the job of warning approaching ships away was doubly important. Rebuilding was in full swing following the great 1906 earthquake. The already hectic harbor was a mad scramble of activity with hundreds of ships attempting to navigate the bay’s treacherous currents, escape ship-eating rocks, and find their way through heavy fog. The lighthouses, fog sirens, and bells were critically important.

Juliet stood on the small platform with a hammer in hand because, once again, the Gamewell Fire Alarm Number 3 clockworks, which powered the mechanism that rang the Angel Island bell, had quit working. During a brief lifting of the fog, Juliet had sent a telegram to the lighthouse engineer and then serviced the small, stationary red light on the southwest corner of the station. Because the light was intended for fair nights and not thick fog, it would be virtually useless as a warning.

To learn more about Juliet Fish Nichols and other such patriots read

Soldier, Sister, Scout, Spy:

Women Patriots and Soldiers on the Western Frontier.

This Day…

Winema – Woman Chief

Winning made easy. Enter to win a copy of the new book

Soldier, Sister, Scout, Spy:

Women Soldiers and Patriots of the Western Frontier.

A lone Native American woman cautiously led her chestnut mare through the bluffs around Klamath Lake, an inland sea twenty miles north of the line dividing California and Oregon. The rider was Mrs. Frank “Tobey” Riddle. She belonged to the Modoc tribe that settled in the area; they called her Winema. She was known among her family and friends as one who possessed great courage and could not be intimidated by danger. She pressed past the jagged rocks lining the transparent water, praying to the great god Ka-moo-kum-chux to give her abundant courage in the face of the certain danger that she was about to encounter.

Winema was a mediator between the Modoc people, other Indian tribes in the area, and the US Army. With her skills, she was able to negotiate treaties that kept the land of her ancestors in peace. Whenever that peace was threatened, her job was to set things straight. She was on her way now to do just that—riding into hostile Modoc territory to persuade the chief to surrender to the cavalry.

Chief Keintpoos, or Captain Jack (a name given to him by the settlers because of his liking for brass buttons and military medals on his coat), was Winema’s cousin. In 1864, the US government forced his people from their land onto a reservation in Oregon. Conditions on the reservation were intolerable for the Modoc people. They were forced to share the land with Klamath Indians of the region. The Modoc and the Klamath tribes did not get along. The latter particularly hated the Modoc people because they had long been defeated by them in battle. Now suddenly their old enemies were moved into their midst. The Modoc Indians struggled to live in this hostile environment for three years. Modoc leaders appealed to the US government to separate the tribes, but officials refused to correct the problem. In 1869, Captain Jack defied the laws of the white man and led his tribe off the reservation and back into the area where their forefathers had first lived.

The cavalry and frustrated members of the Indian Peace Council wanted to use force to bring Captain Jack and his followers back to the reservation. Winema persuaded them instead to give her a chance to talk with the chief. “No peace can be made as long as soldiers are near,” she told them. “Let me speak with my cousin and see what can be done without war.”

As Winema made her way around the jagged sides of the mountains, she thought of her son. Before she’d left on her journey, she’d held the infant in her arms and kissed his lips. Although she was traveling under a flag of truce, she considered the possibility of being seen as a traitor by her people and being struck down before she could plead her case. She shuddered a moment at the thought, then, with a set face, spurred her horse forward. I will see my little boy again, she promised herself.

When Winema reached the Modoc camp, Captain Jack’s men gathered around her. A dozen pistols were drawn upon her as she dismounted. She eyed the angry tribesmen as they slowly approached her. Then, walking backward until she stood upon a rock above the mob, she clasped her right hand upon her own pistol, and with the other on her heart she shouted aloud, “I am a Modoc myself. I am here to talk peace. Shoot me if you dare, but I will never betray you.” Her bravery in the face of such difficulty won the admiration of her people, and, instantly, a dozen pistols were drawn in her defense.

To learn more about Winema and other such patriots read

Soldier, Sister, Scout, Spy:

Women Patriots and Soldiers on the Western Frontier.

This Day…

Frances Boyd – The Lieutenant’s Wife

Enter to win a copy of the new book

Soldier, Sister, Scout, Spy:

Women Soldiers and Patriots of the Western Frontier.

Frances eyed the horizon before them then disappeared into the wagon. She picked up two sabers lying next to a trunk, unsheathed them, and thrust them out either side of the back of the wagon. From a distance she hoped it would look like they were armed with more travelers who were ready to do battle with the Apaches. Unless they come very close, she thought, the dim light will favor our deception.

She returned to her husband’s side, cradling a pistol in her lap. The strap on Orsemus’ gun in his holster had been undone, and he was ready to fire his weapon as well. The riders in front of them had pulled their bayonets from their sheaths, the blades gleaming in the low-hanging sun. Frances believed the small band looked as warlike as possible. Members of the Eighth Cavalry had passed this same way a few days before and had been assaulted with bullets from some of Apache leader Geronimo’s warriors. Frances and the others were relying on an appearance of strength they in nowise possessed. They knew the Natives would not attack unless they were confident of victory.

The train proceeded into the canyon. The mountain walls on either side were jagged and high. They were a treacherous color against which an Indian could hide himself and almost seem to be a part of them. Frances later wrote that their “hearts quivered with excitement and fear at the probability of an attack.”

The going was slow, and, as time progressed without any hint of an ambush, the party started to relax. Then, suddenly, they heard the fearful cry of an Indian. His cry was answered by another.

Frances stared down at her baby lying at her feet. The child was bundled up in many blankets and sleeping soundly. Orsemus urged on the mule team pulling the wagon through the imposing gorge. Everyone with the party believed death was moments away. “At last, and it seemed ages,” Frances later recalled, “we were out of the canyon and on open ground.” The Boyds eventually met up with a large party of freighters and made their way to the northern part of the state, frazzled but unharmed. Thus was the life of a military wife on the wild frontier.

Women like Frances Boyd chose to endure the hardships of army living in order to make life for their husbands less burdensome and to help settle an untamed land. “I cast my lot with a soldier,” Frances wrote in her memoirs, “where he was, was home to me.”

Frances Anne was born into a well-to-do family in New York City on February 14, 1848. Her father owned a bakery; her mother was a housewife who died when Frances was quite young. Historians record that she was a bright girl with an agile mind. She met Orsemus Boyd when she was a high school senior and he was a cadet at West Point. They were married a year later, on October 9, 1867. Orsemus had a desire to go west, and Frances had a desire to be with Orsemus.

To learn more about Frances Boyd and other such patriots read

Soldier, Sister, Scout, Spy:

Women Patriots and Soldiers on the Western Frontier.

This Day…

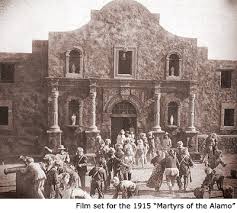

Juana Navarro Alsbury – Alamo Survivor

Enter to win a copy of the new book

Soldier, Sister, Scout, Spy:

Women Soldiers and Patriots of the Western Frontier.

The distant cadence of drums from the nearly deserted town of San Antonio de Bexar sent a shiver of fear through Juana Navarro Alsbury. She clutched her baby son closer and strained to hear. Mexican president and General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, enemy of her uncle and her husband, had come when least expected, bringing thousands of men and artillery as well as a thirst for vengeance. The baby wailed at the nearby roar of exploding powder from the cannon mounted at one corner of the Alamo.

That shot signaled defiance by the Texians (Texans from the United States) and Tejanos (Texans of Mexican descent) holed up in the old mission. Juana soothed the baby and waited, holding her breath for Santa Anna’s response.

It was said he had 1,500 to 6,000 troops, cavalry, and cannon at his command. Inside the crumbling fortress were several dozen women and children protected by fewer than 200 defenders. Juana’s new husband, Dr. Horatio A. Alsbury, had galloped off to find volunteers to join the fight, leaving Juana and the baby behind.

Dr. Alsbury had warned that Santa Anna would come down with a heavy hand on the Tejanos and Texians who had settled in the area. Her husband’s activities were known to the Mexican dictator, as were those of her father, who opposed Santa Anna’s overthrow of the constitution of 1824. Her father’s brother, Jose Antonio, had put his name on the Texas Declaration of Independence. If the Alamo fell under the general’s onslaught, the respected name of her Spanish forebears would not protect her little family.

Juana recognized the futility of attempting to hold off the overwhelming force of hardened troops surrounding the old mission-turned-fortress. Those inside the Alamo’s walls were also ill-prepared to fight Santa Anna, in part because too many people had discounted the Mexican dictator’s determination. He had already killed all prisoners taken in a battle the year before and been granted by the Mexican government permission to treat as pirates all Tejanos as well as Texians found armed for battle, meaning they would be executed immediately.

The Tejanos and Texians had dismissed reports that the Mexican dictator was nearby. After all, they argued, two blue northers had recently swept through the area, their freezing winds covering the barren landscape to the south with snow. What commander would move his troops, many of them barefoot, in such conditions?

Enter to win here:

To learn more about Juana Navarro Alsbury and other such patriots read

Soldier, Sister, Scout, Spy:

Women Patriots and Soldiers on the Western Frontier.