1851 – Major James Savage discovered Yosemite Valley in California while chasing Indian.

Difficulties with Dick Vann

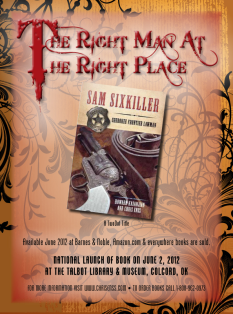

This is the last week to enter to win a copy of the award winning book

Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman

It was a warm September evening in 1886 when the citizens of Muskogee gathered in the center of town to enjoy a concert given by the Muskogee Amateur Italienne Musical Society. Horses and wagons lined the streets. The performers tuned their instruments and greeted crowd members anxious to express their support for them. Excited children chased one another around and families jockeyed for the best positions in front of a crude bandstand. Women huddled together in discussions of their own and comforted the infants with them that were unsettled by the flurry of activity.1

Before the event had officially begun, the sound of rapid gunfire echoed off the buildings that framed the main thoroughfare. The gunshots grew louder and suddenly a pair of horsemen appeared riding pell-mell toward the congregation. People scattered. Running for cover, they disappeared into businesses and homes. The cries of astonishment and fear from the unassuming townspeople had no effect on the two rides. Black Hoyt, a half-blooded Cherokee Captain Sixkiller had previous dealings with, and a white man named Jess Nicholson gouged the spurs on their boots into the sides of their mounts and charged down the street, shooting their weapons at anything that moved.2

The out of control men were drunk and enjoying the chaos derived by their wild behavior. Captain Sixkiller and the police officers that worked with him, including Charles LeFlore, rushed onto the scene brandishing their own guns. The captain shouted at Black and Nicholson to stop, but the men took their time at it. After a few moments waiting for the two rowdies to do as they were told, the Muskogee police force managed to corner the riders. LeFlore ordered them to throw their pistols down, and Captain Sixkiller informed them they were under arrest. Neither of the men complied.3

A tense hush filled the air as Black and Nicholson considered their options. The captain studied the belligerent looks on their darkly flushed features. “Give us your guns now,” he demanded, “before someone gets hurt.” Black shifted in his saddle and rubbed off the sweat standing on his chin with his right shoulder. His arm was missing from the elbow down, and his shirtsleeve was pinned over the remaining portion of the limb. Black had lost his arm in June 1886, after he was shot by an unknown assailant while at Fort Gibson, Oklahoma. A bullet fractured the lower third of the appendage, and amputation was his only chance of recovery. Black and his father objected at first but, after conferring with a second doctor, realized there was no other option. He recovered quickly from the chloroform, and as soon as he could left the post doctor’s office to avoid any further attempts on his life. With Milo’s help, he learned how to ride and shoot holding the reins of his horse and pistol in the same hand.4

To learn more about the life and times of Sam Sixkiller read

Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman

This Day…

Keeping the Peace

Enter to win a copy of the award winning book

Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman

Captain Sam Sixkiller crossed the timber lined banks of the Arkansas River atop a big, brown roan. The well-traveled trail lay out in front of him looked like an ecru ribbon thrown down across the prairie grass. Riding a few paces behind the lawman was Deputy Bill Drew. Neither man spoke as they traveled. A herd of cattle in the near distance plodded along slowly toward a small stream. A couple of calves held back, bawling for their mothers who had left them a safe distance behind. Upon reaching the stream the cows buried their noses in the water. They paid no attention to the approaching riders as they enjoyed a refreshing drink.1

Captain Sixkiller pulled back on the reins of his horse, slowing the animal’s pace. He stared thoughtfully considering the proximity of the cattle to the crude camp behind the field of prairie grass reaching into the horizon. Deputy Drew watched the captain, waiting for the officer to proceed. Both men knew the danger inherent in the job they’d set out to do in early January 1886. They were tracking a murderer named Alfred “Alf” Rushing also known as Ed Brown.2

Nine years prior to Captain Sixkiller leaving Muskogee on a cold winter’s day to apprehend Rushing, the elusive rowdy had shot and killed the marshal of Wortham, Texas.3 The Houston and Texas Central Railway ran through the busy cotton farm community of Wortham, attracting nefarious characters like Rushing. Rushing was a cattle rustler and bootlegger who hoped to make a fortune selling liquor and robbing business owners in the farming town. On December 8, 1879, Rushing and two accomplishes had ridden into Wortham and made their way to J.J. Stubb’s general store. All three were armed with shotguns and hell-bent on retrieving a pistol they claimed Stubbs had stolen from them.4

It wasn’t the first time Stubbs had been accused of stealing the pistol from Rushing. Although he denied taking the gun, the men continued to come around and harass him for the item. They refused to accept the storeowner’s claim that he knew nothing of it. Rushing finally told him they intended to get $17 for the weapon before he left or there would be “hell to pay.” 5

The volatile display Rushing and his cohorts, Harv Scruggs and Frank Carter, made attracted the attention of Wortham’s dutiful and dedicated city marshal, Jackson T. Barfield. According to the newspaper, the Galveston Daily News, “Marshal Barfield quietly walked across the street (from the jail) to the store and asked the men in a friendly manner not to raise a disturbance and to be more quiet.6

The marshal was not accused to his face of having taken the pistol, but seemed to be trying to pacify them and apprehend no danger to himself. Turning his back upon them to walk off, he was shot in the back by Alf Rushing with nine buckshot passing through his body and three through the heart.

To learn more about the life and times of Sam Sixkiller read

Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman

This Day…

Badman Dick Glass

Enter to win a copy of the award winning book

Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman

Sheriff John Culp and Constable Rush Meadows of Chick County, Texas, raced their foam-flecked horses into a dense stand of trees leading to the Arbuckle Mountains, several miles north of Muskogee. The seasoned riders guided their mounts around centuries-old pines and oaks, rotting with age, and massive boulders keeping company with the crowded forest.

The lawmen were in pursuit of outlaw Dick Glass. Glass rode hard, maneuvering his horse in and out of downed timbers. An insane rage possessed him, and he could not allow himself to be caught. He dug his heels into his ride and steered the animal toward an embankment. A wind that seemed to blow from the outer spaces of eternity swept his hat off. He didn’t even glance after it.1

The $1,000 reward for Glass’s captured spurred the officers on.2 Glass was a Creek Freedman, half Indian, half black man and one time farmer in the Creek Nation. When the Civil War ended in 1865, all the slaves of Indians became free and equal. Generations of Creek Freedmen had been raised on the land they worked, and they wanted part of it for their own once the battle between the states had concluded. Not only was their request denied, but they were dispossessed because they weren’t Indian. Men like Dick Glass were bitter over the treatment and turned to a life of crime and retaliation.3

In late March 1885, Glass and the gang of miscreants that usually rode with him were run out of the Creek Nation for rustling cattle, stealing horses, and murdering. He reluctantly obliged, taking with him other Creek Freedmen who had partnered with him in his lawless activities.4

Glass roamed through the Seminole, Pottawatomie, and Chickasaw Nations to the Texas line before settling a spot seven miles from Muskogee known as the Point. Glass and his gang made their way back to the Point after every criminal act. It was their rendezvous location, and lawmen that came looking for him there and found him never lived long enough to report it. There were no cabins, lean-tos, or barns on the property. Glass and the other desperados slept outdoors, subjected to the various elements.5

The life of a renegade was tiring and uncomfortable; it was with this in mind that Glass decided to repent from his devious ways and set a new course. According to the letter he sent to the editors of the Indian Journal newspaper to be posted on the front page, Glass “wished to become a law abiding citizen if the police would not molest him.” The price already on his head made the proposition impossible to accept.6

Texas lawmen Culp and Meadows were not swayed by Glass’s promise to reform. They were going to bring him in regardless. They pushed on at a hard and steady gait through the terrain. The men brought their horses to a quick halt once they reached a clearing in the trees at the base of the mountains. Glass was sitting atop his nearly exhausted ride waiting for them. The lawmen approached the scene cautiously. A flash of satisfaction filled the sheriff’s face as he surveyed the area for signs of anyone who might be coming to Glass’s aide. Satisfied that Glass had simply given up, Culp ordered the outlaw to throw up his hands.7 Glass had no intention of obliging. His hand streaked down toward the holster on his thigh. Sheriff Culp and Constable Meadows beat him to the draw and Glass was pitched off his horse.8

Once the smoke had cleared, the lawmen holstered their weapons and dismounted. They exchanged a congratulatory glance as they slowly approached the criminal lying in a heap on the ground. Glass was of average height and weight with a scar across the side of his neck, running from his ear down to his chest. It was a burn of some kind over which the skin had grown back red instead of black. It was a distinctive marking, one that made it easy to recognize him in any situation. Glass also had a scar on one hand, made by a bullet that had passed through it when he was in one of his shooting scrapes. Any fleeting doubt the lawmen might have had that the body lying motionless on the ground was anyone other than Glass was removed.9

To learn more about the life and times of Sam Sixkiller read

Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman

This Day…

Defending a Nation

Enter to win a copy of the award winning book

Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman

A springboard wagon topped a ridge surrounded by a grove of ancient juniper trees seven miles outside Muskogee. The wagon was weighted down with several heavy crates and made little sound. The contents inside the crates slouched as the vehicle slogged through the rain-soaked turf. The soft ground muffled the hardworking wheels and the horse’s hooves. Solomon Coppell, an unshaved man dressed in a dirty, fawn-tan suit with a long-tailed coat, drove the wagon over a crude trail cut deep in mud and dirt. His roving button eyes scanned the scene in front of him, looking for anything out of the ordinary.

Just beyond Solomon’s line of sight, tucked behind a thicket of brush, Captain Sam Sixkiller sat on his horse watching him.1 Sweat rolled down the lawman’s face as the sun in late spring of 1883, riding up into a leaden sky, empty and cloudless, and touched the captain with a sticky heat. Solomon was uncomfortable too. He pulled off the flat-brimmed $50 hat on his head and backhanded a bead of perspiration off his hairline. He then put his hat back on as he continued along his way. The captain waited for just the right moment and then in one fast, flawless movement spurred his horse onto the trail directly in front of Solomon’s team.

A stunned Solomon quickly jerked back on the reins of the animals and brought the skittish horses to a stop. “Hold it, Coppell!” Captain Sixkiller announced in a sober, stern voice. “You’re under arrest.” Solomon glanced at the cargo he was hauling and back to the captain. The lawman was alone and the bootlegger was confident he could survive a confrontation with his wagon load intact. Solomon stared at the captain for a moment shaking his head. “I got a tip you were bringing booze into the Nation,” the captain informed him. Solomon didn’t reply and showed no signs of cooperating “Surrender, Coppell,” Captain Sixkiller warned him again. “Throw your guns out in the road.” The captain was empty-handed, his leg gun still resting in a holster on his thigh. Coppell made a grab for the shotgun on the wagon seat.2 The captain’s hand whipped forward in a short, small arc. There was no strain. He saw Coppell’s face, distorted and desperate. His gun kicked back against his wrist. One shot. He saw Coppell’s body jerk. Captain Sixkiller’s gun exploded before it cleared his coat. He saw the flame of the shot lick through the fabric and curl to form a smoldering ring. Coppell swayed and fell into the trace chains and wagon tongue. The team reared and snorted and pawed at the air. The captain calmed the horses and kept them from running away.3

Most Muskogee residences agreed that Captain Sixkiller was an effective policeman, quick to enforce the laws regarding the buying and selling of alcohol. Some thought the rules should be relaxed. Cherokee Indian business owners believed they should have the right to purchase liquor to be sold to white railroad workers and settlers passing through. Indian leaders maintained such measures would lead to an increase in violence on the Nation and insisted that troublemakers who peddled whiskey were to be stopped.4

Although Captain Sixkiller was never accused of being too harsh on those who violated the law, there were Indians like former chief of the Cherokee Nation, Lewis Downing and Indian agents like John B. Jones who thought that the United States marshal and his deputies went too far in upholding the law. “Some deputy marshals make forcible arrests,” Chief Downing told Indian agent Jones in a letter, “without regard to circumstances or the facts of the case, and without any of the forms of law.”5 Smugglers occasionally planted whiskey on innocent people making their way across the Nation. If they were stopped by Captain Sixkiller or his deputies and alcohol was found in their possession they were arrested and taken immediately to Fort Smith, Arkansas, to be prosecuted. Chief Downing strenuously objected to the captain’s rush to judgment and believed in those instances such individuals should be given the benefit of the doubt.6

To learn more about the life and times of Sam Sixkiller read

Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman

This Day…

Mayhem in Muskogee

Enter now to win a copy of the award winning book

Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman

A hot sun beat down on the busy residents of Muskogee, Oklahoma, in June 1880. A heavy veil of humidity, like a stifling blanket hung over the town as well.1 The primitive railroad stop was slowly coming into its own. More than five hundred people called the area home, among them were employees of the Missouri-Pacific Railroad. The workers gathered by the score and milled about the hamlet of lean-tos, tents and cabins. Gamblers had pitched their canvas dwellings in prime spots, and crowds flocked around their tables. Quarrels flared up between slick poker dealers and inexperienced card players. Soiled doves prowled around the gaming tents and curious male bystanders like panthers. They enticed men looking for a fight to their crude dens then stripped them of any funds they had not lost in a crooked card game. Unsuspecting shoppers and their families roamed in and out of the heated arguments that made it into the street. They gawked warily at the chaos while on their way to and from various stores.2

City officials watched the scene play out in disgust. Bootleg alcohol was usually sold to the railroad crews and the houses of ill repute, and the clientele had a hard time controlling the amount they consumed. More often than not customers who frequented bawdy houses and who drank to excess were prone to violence.3 They terrorized the neighborhood surrounding the brothels, recklessly firing their guns at women and children and brawling with townsmen who challenged them to put away their weapons.4

In spite of repeat warnings from law enforcement officers like Colonel J.Q. Tuffts, a United States Agent for the Union Indian Agency in Muskogee, to the madams who ran the brothels to shut their businesses down voluntarily, no efforts had been made by them. Brothels were considered a necessary evil; a portion of the income spent at such houses supported public services such as the police department.5 Agent Tuffts didn’t care about that. He considered the bordellos a hangout for criminals and delinquents from all over the area. When Agent Tuffts made Sheriff Sixkiller captain of the Indian police in early February 1880, he made ridding Muskogee of such houses a priority for Sam’s administration.6 Anxious to prove himself in Muskogee since leaving office under a cloud of turmoil in Tahlequah, Sixkiller was eager to accept the job and the challenge.7

Captain Sixkiller and seven deputies, representing the full force of the police force, marched through the streets of Muskogee to a house in the red light district occupied by the most sought after working women in town. A sign in front of the structure read Hotel de Adams.8 Captain Sixkiller and his men stopped short of the building and studied their next move carefully. A couple of cattle punchers tromped out of the enterprising establishment and headed off in the opposite direction of the lawmen unaware anything out of the ordinary was about to happen. Laughter wafted out through the open windows of the building. Captain Sixkiller motioned for deputies on his left and right to cover the back of the business. When he thought the men had time to get into place he moved up the dusty path to the front door with the other lawmen.9

Use this form to enter to win!

To learn more about the life and times of Sam Sixkiller read

Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman