1860-Phoebe Ann Moses was one day old. Better known as Annie Oakley she was born on August 13th.

The Rights of Women

Don’t miss this double giveaway! Enter now to win two books! Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen and the new book More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen.

The memory of Ellen Clark Sargent’s arrival in Nevada City, California, stayed with her all her life. Long after she had left the Gold Country, she recalled: “It was on the evening of October 23, 1852 that I arrived in Nevada [City], accompanied by my husband. We had traveled by stage since the morning from Sacramento. Our road for the last eight or ten miles was through a forest of trees, mostly pines. The glory of the full moon was shining upon the beautiful hills and trees and everything seemed so quiet and restful that it made a deep impression on me, sentimental if not poetical, never to be forgotten.”

In the newly formed state of California, shaped by men and women who had endured unbelievable hardships to cross the plains, Ellen saw an opportunity to gain something she passionately wanted – the right to vote. Despite defeat after defeat, she never gave up.

Ellen Clark fell in love with Aaron Augustus Sargent, a journalist and aspiring politician, in Newburyport, Massachusetts, when they were in their teens. Both taught Sunday school in the Methodist Church. Upon their engagement, Aaron promised to devote his life to being a good husband and making their life a happy one. But several years passed before he had a chance to make good on that promise.

To learn more about Ellen Clark Sargent and others like her who left their mark on the American West read Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen and More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen.

Guardian of Yosemite

It’s a double giveaway! Enter now to win two books! Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen and the new book More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen.

On December 27, 1902, the woman many historians referred to as the “Guardian of Yosemite National Park” passed away. According to the December 29, 1902, edition of the Fort Wayne Evening Sentinel, “Mrs. Fremont was a remarkable woman, to whom the territory west of the Mississippi River owes more than to any other person perhaps in the country. She helped bring about the preservation of more than twelve-hundred square miles of land in Northern California known as Yosemite. She wielded an influence second to but few statesmen of her generation.”

Jessie Anne Benton Fremont was born on May 31, 1824, in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. Her father, Thomas Hart Benton was an ambitious man who went from farming into politics and eventually became a United States senator from Missouri (and great-uncle of 20th century muralist Thomas Hart Benton). Jessie visited Washington, D.C., often as a child and met with such luminaries as President Andrew Jackson and Congressman Davy Crockett.

Jessie and her sister, Elizabeth, attended the capital’s leading girl’s boarding school, alongside the daughters of other political leaders and wealthy business owners. It was for that very reason Jessie disliked school. “There was no end to the conceit, the assumption, the class distinction there,” she wrote in her memoirs. In addition to the lines drawn between the children of various social standings, Jessie felt the studies were not challenging to her. “I was miserable in the narrow, elitist atmosphere. I learned nothing there,” she recalled in her journal. The best thing about attending school was the opportunity it afforded her to meet John Fremont, the man who would become her husband.

To learn more about Jessie Fremont and others like her who left their mark on the American West read Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen and More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen.

This Day…

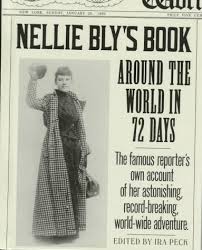

Around the World in Less Than Eighty Days

Don’t wait! Enter now! It’s a double giveaway. Enter now to win two books! Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen and the new book More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen.

On a summer day in the early 1880s an article called “What Girls Are Good For” appeared in the Pittsburg Dispatch. It took a firm stand against the new fad of hiring women to work in offices and shops. “A respectable woman,” the article noted with authority, “remained at home until she married.” If a husband eluded her, she had two choices left. She might go into teaching or into nursing, provided money for her training could be wangled from a reluctant father. Otherwise, she stayed under his roof or that of a relative and for the remainder of her life accepted the status of house worker or child’s nurse, without pay.

The article expressed the customary male sentiments of the day, more emphatically than usual because the editors were stirred up over the inroads being made by suffragettes. Radical females like Susan B. Anthony, openly militant in regard to votes for females, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, champion of women’s rights, went striding up and down the country with a following of “bloomer girls.” Nobody knew better than the Dispatch’s managing editor, George A. Madden, that since the Civil War the manpower shortage had increasingly drawn women into mills and factories, but he felt a barricade must be erected against such an alarming trend. Women in politics were unthinkable, as obviously out of place there as they would be in such a masculine stronghold as his own, a newspaper office.

The article received the expected male commendation from Mr. Madden’s business associates. He was happily married and his wife, busy with children, made no comment. Other matters had taken its place in his active editorial mind when a few days later his memory was refreshed. Going through the morning mail, he read a letter and winced. Then he read it again, and a third time, even though it bore no signature, and for a reason. It was a reply to the “What Girls Are Good For” story, and it sizzled. It was a rebuke to the newspaper’s old fashioned attitude, a declaration of independence for women, a war cry to them to take their proper place in a man’s world to lead interesting, useful, and profitable lives.

The anonymous communication was well written, blazing with conviction. But there was more than that to challenge Mr. Madden’s interest. It made sense.

The busy editor finally tossed it into the pile, finished the remainder of the mail, and went back to reading the tissue-paper slips bearing the telegraphic news. But when he had them impaled neatly on the nearby spindle, he took up the letter again. It intrigued him. He studied the handwriting. It appeared feminine, as feminine as the attitude it expressed. But surely no woman could write so logically and so eloquently.

He could not publish the thing, even with a signature. It was against his principles, against popular opinion. But he did want to know who had sent it. An idea came to him. He would advertise in the columns of the Dispatch for the writer’s name and address, and, if he obtained them, he might assign a story to be written on the other side of the question. The author would turn out to be a man, of course, perhaps taking this way to attract attention and get a job. Madden would certainly give him one if he wrote like this consistently.

The advertisement appeared the next day. A reply came almost at once.

The letter was written by a woman. Her name was Elizabeth Cochrane, and she lived in Pittsburgh.

George Madden was a newspaperman by both training and instinct; he always followed a hunch. He wrote to Miss Cochrane and asked for an article on “Girls and Their Spheres in Life.”

Again she was prompt; the article arrived within a few days. The editor read it and found it good. He paid for it. Then he abandoned caution. Fortifying himself, for he was positive he was opening the door to a battle-ax suffragette, he suggested that Elizabeth Cochrane might like to discuss further work for his paper. The two men and Elizabeth accepted a position as reporter for the paper.

Elizabeth Cochran, or Nellie Bly as she was also known, was born on May 5, 1867, in Armstrong County, Pennsylvania. According to friends and family, Nellie aspired to be more than what the stereotypical young girl was supposed to be. She liked traveling, adventure, and writing in depth stories. She moved to Pittsburgh at the age of seventeen to pursue her dream of being an investigative reporter. Her first assignment for the Dispatch was to tackle the subject of divorce. She penned numerous articles for the paper ranging from conditions for workers in factories to the treatment of the mentally ill in asylums.

To learn more about Nellie Bly and others like her who left their mark on the American West read Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen and More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen.

This Day…

The Finest of Us All

Enter Now! It’s a double giveaway. Enter now to win two books! Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen and the new book More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen.

Legendary lawman and sportswriter Bat Masterson once referred to his well-known colleague Bill Tilghman as “the finest among us all.” Marshall Tilghman and Sheriff Bat Masterson were two members of the “most intrepid posse” of the Old West, a group of policemen who in 1878, tracked down the killer of a popular songstress named Dora Hand.

William Matthew Tilghman, Jr.’s drive to legitimately right a wrong began at an early. He was born on the 4th of July 1854 in Fort Dodge, Iowa. His father was a soldier turned farmer and his mother was a homemaker. Bill spent his early childhood in the heart of the Sioux Indian territory in Minnesota. Grazed by and arrow when he was a baby, he was raised to respect Native American and protect his family from tribes that felt they had been unfairly treated by the government. Bill was one of six children. He mother insisted he had been “born to a life of danger.”

In 1859 his family moved to a homestead near Atkinson, Kansas. While Bill’s father and oldest brother were fighting in the Civil War, he worked the farm and hunted game. One of the most significant events occurred when he was twelve years old while returning home from a blackberry hunt. His hero Bill Hickok rode up beside him and asked if he had seen a man ride through with a team of mules and a wagon.

To learn more about Bill Tilghman and others like him who left their mark on the American West read Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen and More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen.

This Day…

Law West of the Pecos

It’s a double Giveaway! Enter now to win two books!

Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen and the new book More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen.

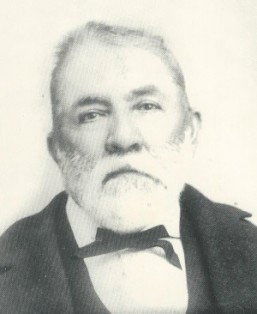

With the passing of Judge Roy Bean, who referred to himself as the “Law West of the Pecos,” the rowdy frontier lost one of its most unique and picturesque characters. It was Judge Bean that was said to have held an inquest on the body of an unknown man found in his precinct, and, finding on the corpse a pistol and $40 in cash, proclaimed the dead man guilty of carrying a concealed weapon and fined him $40, which was forthwith collected from the pocket of the offender.

There were no customers from Judge Roy Bean’s opera house and saloon by his side when he died on March 16, 1903; no friends from the Langtry, Texas, community where he had resided; no lawbreakers to be tried and sentenced. Judge Bean’s son, Sam, was the only one with him when he passed.

The stout, seventy-eight year old man with a gray beard spent his last hours on earth in a near comatose state unaware of where he was or whom he was. He died of heart and lung complications exasperated by alcohol.

To learn more about Judge Roy Bean and others like him who left their mark on the American West read Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen and More Tales Behind the Tombstones: More Deaths and Burials of the Old West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Lawmen.