1875 – Billy the Kid is arrested for the first time.

Where Thanksgiving Traditions Are Still Observed

Win a book for the holidays. Enter to win a copy of the children’s book

Cowboy True’s Christmas Adventure.

Prospectors and mining camp followers in the Gold Country in 1869 began making plans for lavish Thanksgiving celebrations in late October. According to the October 20, 1869 edition of the Daily Alta newspaper, boarding house owners attracted Argonauts and camp followers for miles around to enjoy the holiday with them. “Judging from the number of Balls coming off, the people of El Dorado seem determined to have a happy time at the “Thanksgiving Ball” that is to be given at the Nevada House in Georgetown,” the Daily Alta article read. “The managers will accept your thanks with a purchase of a ticket. In addition to the ball a feast will be served including turkey and all the trimmings. The history of Thanksgiving Day reaches back to the early colonial days, when a little band of strong hearted and earnest men and women who had ventured across the seas in search of freedom and life and liberty came to this country.”

To learn more about how Cowboy True celebrated the holidays read

Cowboy True’s Christmas Adventure.

All proceeds raised from the sale of the book go to benefit

UC Davis Children’s Hospital.

Staring Down a Rattlesnake

Last chance to enter to win a copy of Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of some of the West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Western Actors and Law men.

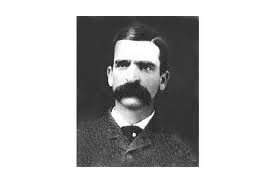

It wasn’t a bullet from an outlaw’s six-shooter or an enemy soldier in the Spanish-American War that claimed the life of one of the fiercest lawmen in the history of the Dakotas. Seth Bullock died of colon cancer. The accomplished businessman, rancher, politician, and lawman suffered with the disease for years and when he died in September 1919 at the age of sixty-two, he was remembered for his strength of character as well as the influence he had on the wild frontier.

Born in Amhertberg, Ontario, Canada in August 1876, Bullock was described by his good friend President Theodore Roosevelt as a “splendid looking fellow with his size and subtle strength, his strongly marked, aquiline face with his big mustache, and the broad brim of his soft hat drawn down around his hawk eyes.”

According to the September 28, 1919 edition of the Kansas City Star, before Seth Bullock made his mark on the Black Hills of Dakota he was a pioneer in Montana. He was the first sheriff in Helena, Montana and a member of a famous vigilance committee which rid the region of a desperate band of horse thieves.

Upon hearing that gold had been discovered in the Black Hills, Seth and some of his friends decided to go to that area of the country in the summer of 1876. In March 1877, he became Lawrence County, Dakota’s first sheriff. The gold camp contained some of the most notorious, cut-throat criminals in the country. Many were intimidated by the lawman.

Seth dressed like a minister, had the stare of a mad cobra, and was silent as a confidential clerk working for Rockefeller. In the beginning, his ability to effectively do his job in Lawrence County was challenged by an outlaw who disliked the lawman intensely. He gave orders that Seth should leave the camp and never return. The man threatened to shoot Seth if he didn’t go. After being warned by friends, the sheriff borrowed a squirrel gun from an old hunter and proceeded down the street to the saloon where the desperado was waiting. When the man saw Seth unafraid and coming right for him he backed down and fled the scene.

As a representative of law and order the Dakota lawman tracked down a number of stage robbers, gamblers, and murderers, and according to the October 1, 1919 edition of the Fort Wayne Journal Gazette killed more than twenty-five lawbreakers who refused arrest.

In addition to his career in law enforcement, (Seth also served as a United States Marshal in Western Dakota Territory) he co-owned and operated a hardware store and warehouse in Deadwood with his business partner Sol Star. It was one of the most prosperous companies in the Black Hills.

Seth met Theodore Roosevelt in 1884. Roosevelt was a deputy sheriff in Medora, North Dakota and had tracked a criminal to Seth’s jurisdiction. The two lawmen became fast friends. He became one of Roosevelt’s Rough Riders in the Spanish-American War and was named captain of one of the future President’s troops.

Seth was an elected representative to the Senate and introduced the resolution to set aside Yellowstone as a national park. He was the first forest supervisor of the Black Hills and the cofounder of the mining town Belle Fourche.

Seth was serving his third term as United States Marshal for the District of South Dakota when he was diagnosed with cancer. Friends and family noted that in spite of his health he refused to be complacent. He continued on with his work regardless of the debilitating illness.

When President Roosevelt died in January 1919, Seth decided to erect a monument in his friend’s honor. He oversaw the building of a stone tower known as Mount Roosevelt on Sheep Mountain located five miles from Deadwood. The tower was completed in June 1919. Seth died on September 23, 1919 at his home surrounded by his loved ones. He was buried at Mount Moriah Cemetery in Deadwood. His grave faces Mount Roosevelt.

To learn more about the death of legendary characters read Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of some of the West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Western Actors and Lawmen.

Down Went the Duke

Giveaway! Enter to win a copy of Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of some of the West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Western Actors and Lawmen

After acting as either a cowboy or a soldier in nearly one hundred films, John Wayne finally won a best actor Oscar in 1969 for True Grit. The quintessential macho man was himself exempt from service during World War II owing to a problem with his shoulder. Winning the Oscar, some say, added another ten years to his life. Although he was a longtime smoker, averaging four packs a day, Wayne nevertheless died of gastric cancer at age seventy-two in 1979. In 1955 John Wayne was among two hundred twenty cast and crew member who worked on the film The Conqueror. It was shot on a location in Utah, which was contaminated by radioactive fallout from atomic bomb tests. Much of the soil was transported back to Hollywood for studio scenes. By 1980 more than ninety of those who worked on the movie contracted cancer; forty-six died. Even though Wayne knew of the danger, often carrying a Geiger counter onto the set, he believed the risk insignificant.

To learn more about the death of legendary characters read Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of some of the West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Western Actors and Lawmen.

This Day…

Death of the Cowboy Philosopher

Enter to win a copy of Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of some of the West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Western Actors and Lawmen

It looks like the only way you can get any publicity on your death is to be killed in a plane. It’s no novelty to be killed in an auto anymore.” Will Rogers had the knack to turn anything into a joke and get away with it. Part Cherokee, Rogers took his lariat tricks from Indian territory in Oklahoma to Broadway, where his shy grin and classic drawl – “All I know is what I read in the paper” – made him the most popular folk hero of his time. He wrote a nationally syndicated newspaper column starting in 1926 and would file it six times a week no matter where he happened to be – which was likely to be anywhere in the world.

In August 1935, Rogers happened to be in Alaska, casually flying around the territory with Wiley Post, a famous globetrotting aviator. “Was you ever driving around in a car and not knowing or caring where you went?” Rogers wrote in his column August 12. “Well, that’s what Wiley and I are doing. We sure are having a great time. If we hear of whales or polar bears in the Arctic, or a big heard of caribou or reindeer, we fly over and see it.” The two men had plans to fly over the Arctic to Siberia and on to Moscow to explore the possibility of making it a regular air route. But they kept their mission secret.

The two men took off from Fairbanks on August 15 for a 500-mile trip to Point Barrow, a barren outpost at the northern tip of Alaska. During the flight Post noticed the plane was heavy in front and had a tendency to pitch forward at low speeds.

There immediate concern on August 15 was the weather. They had been warned of dense fog along their route but Post just said, “I think we might as well go anyway.” Rogers agreed and pointed out, “There’s lots of lakes we can land on.” About 50 miles from Point Barrow the fog got bad enough that Post did indeed land but, unsure of their route, they landed on a shallow river 15 miles from Point Barrow to ask directions from some Eskimos.

At 5 p.m. they took off, again. About 50 feet in the air, before they had even reached the end of the water, the engine sputtered. Post turned sharply to the right, then the plane plunged nose-first into the edge of the stream into about two feet of water. The right wing was torn off and the plane came to a rest upside down. Both men were killed instantly. Post was crushed by the engine, which had been forced back into the cockpit. Rogers was also killed by the impact, thought he had been seated farther back in the plan, probably to try to counterbalance the front-end heaviness. It was unclear why the engine misfired, but some have speculated that the plane was out of gas.

After the crash an Eskimo who had given them directions ran 15 miles to Point Barrow to report what he had seen. It took him three hours. It was dark by the time a U.S. Army sergeant set out in a whale boat through the icy waters. He towed the bodies back to Barrow in a skin boat.

Will Rogers was buried in his hometown of Claremore, Oklahoma.

To learn more about the death of legendary characters read Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of some of the West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Western Actors and Lawmen.

Colorado Ryan

Take a chance. Enter to win a copy of Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of some of the West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Western Actors and Lawmen

Eric Hilliard Nelson was a well known teen idol, thanks to the family radio and television show The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet. His song “Poor Little Fool” ranked number eight-three of all-time most popular songs of the twentieth century. In 1985 at age forty-five Rick died in a plane crash while heading to a New Year’s Eve concert, attempting to stage a revival of his career. The last year of his life he earned nearly $700,000 from his music, but because of heavy alimony payments and, some say, an even heavier cocaine habit, he had only $40,000 left. He knew the forty-year-old charter plane the band owned needed service, though he felt that making it to the gig was more important. The plane burst into flames, with reports blaming it on the band’s free-basing as a reason for the massive fire that left Nelson and six of the band members identifiable only by dental records.

To learn more about the death of legendary characters read Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of some of the West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Western Actors and Lawmen.

Killing Sitting Bull

Enter to win a copy of Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of some of the West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Western Actors and Lawmen

In an earlier time Sitting Bull might have been a great and prosperous Indian chief. But in the second half of the 19th century he was the last ruler of a dying breed. His victory over General Custer at Little Big Horn in 1876 was but a glitch in the United States drive to corral the Sioux Indians onto reservations. A medicine man and never actually a chief, Sitting Bull led a dwindling number of Sioux away from federal troops for five more years, until finally, in 1881, he and fewer than 200 remaining followers surrendered. They were held in custody for almost two years before they were placed on the Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota, near where Sitting Bull was born.

Sitting Bull, a tall, solid Indian with long, black, braided hair, was put on parade in several cities and in 1885 he toured with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show along the East Coast. But when he was on the reservation Sitting Bull stubbornly continued to stir up unrest. Even after federal authorities prohibited the ceremony, Sitting Bull encouraged Indians to perform the new Ghost Dance, which the Indians had come to believe would lead to a rebellion and would bring a savior to defeat the White Man.

At dawn on December 15, 1890, about forty members of an Indian police force commissioned by federal authorities descended on Sitting Bull’s cabin to arrest him. They pulled the 59-year-old naked man from his bed and ordered him to get dressed and go with them. Sitting Bull gathered his things, but he took a long time to do it, which allowed time for a restless crowd of Indians to gather outside. By the time Sitting Bull was roughly pushed out of his cabin into the freezing weather, the crowd was angry.

Sitting Bull stood waiting for his horse to be brought up. But then suddenly he yelled in the Sioux language – which the Indian officers, too, understood – “I am not going. Do with me what you like. I am not going. Come on! Come on! Take action! Let’s go!” Another leader of unrest on the reservation, Catch the Bear, pulled out a gun and fired at the top Indian officer. Lieutenant Bullhead was hit in the leg and as he fell he fired at Sitting Bull, shooting him in his left side. Another officer also shot the Indian leader, killing him instantly. The gun battle escalated, and when it was over fourteen men were dead, all Sioux, including six Indian police officers. Hundreds of other fled the reservation. Most were soon caught and sent to Wounded Knee, where on December 29, an anonymous gunshot touched off the massacre of 300 Sioux.

To learn more about the death of legendary characters read Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of some of the West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Western Actors and Lawmen.

This Day…

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

Feeling lucky? Enter to win a copy of Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of some of the West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Western Actors and Lawmen

After acting as either a cowboy or a soldier in nearly on hundred films, John Wayne finally won a best actor Oscar for True Grit (1969). The quintessential macho-man was himself exempt from service during World War II owing to an inner ear problem and a shoulder injury. Winning the Oscar, some say, added another ten years to his life. Although he was a longtime smoker, averaging four packs a day, Wayne nevertheless died of gastric cancer at age seventy-two in 1979.

In 1955 John Wayne was among two hundred twenty cast and crew members who worked on the film The Conqueror. It was shot on a location in Utah, which was contaminated by radioactive fallout atomic bomb tests. Much of the soil was transported back to Hollywood for studio scenes. By 1980 more than ninety of those who had worked on the movie contracted cancer; forty-six died. Even though Wayne knew of the danger, often carrying a Geiger counter onto the set, he believed the risk insignificant.

To learn more about the death of legendary characters read Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of some of the West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Western Actors and Lawmen.