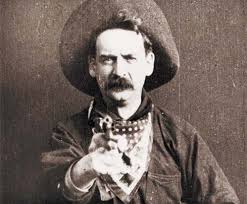

Enter to win a copy of Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of some of the West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Western Actors and Lawmen

In an earlier time Sitting Bull might have been a great and prosperous Indian chief. But in the second half of the 19th century he was the last ruler of a dying breed. His victory over General Custer at Little Big Horn in 1876 was but a glitch in the United States drive to corral the Sioux Indians onto reservations. A medicine man and never actually a chief, Sitting Bull led a dwindling number of Sioux away from federal troops for five more years, until finally, in 1881, he and fewer than 200 remaining followers surrendered. They were held in custody for almost two years before they were placed on the Standing Rock Reservation in South Dakota, near where Sitting Bull was born.

Sitting Bull, a tall, solid Indian with long, black, braided hair, was put on parade in several cities and in 1885 he toured with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show along the East Coast. But when he was on the reservation Sitting Bull stubbornly continued to stir up unrest. Even after federal authorities prohibited the ceremony, Sitting Bull encouraged Indians to perform the new Ghost Dance, which the Indians had come to believe would lead to a rebellion and would bring a savior to defeat the White Man.

At dawn on December 15, 1890, about forty members of an Indian police force commissioned by federal authorities descended on Sitting Bull’s cabin to arrest him. They pulled the 59-year-old naked man from his bed and ordered him to get dressed and go with them. Sitting Bull gathered his things, but he took a long time to do it, which allowed time for a restless crowd of Indians to gather outside. By the time Sitting Bull was roughly pushed out of his cabin into the freezing weather, the crowd was angry.

Sitting Bull stood waiting for his horse to be brought up. But then suddenly he yelled in the Sioux language – which the Indian officers, too, understood – “I am not going. Do with me what you like. I am not going. Come on! Come on! Take action! Let’s go!” Another leader of unrest on the reservation, Catch the Bear, pulled out a gun and fired at the top Indian officer. Lieutenant Bullhead was hit in the leg and as he fell he fired at Sitting Bull, shooting him in his left side. Another officer also shot the Indian leader, killing him instantly. The gun battle escalated, and when it was over fourteen men were dead, all Sioux, including six Indian police officers. Hundreds of other fled the reservation. Most were soon caught and sent to Wounded Knee, where on December 29, an anonymous gunshot touched off the massacre of 300 Sioux.

To learn more about the death of legendary characters read Tales Behind the Tombstones: The Deaths and Burials of some of the West’s Most Nefarious Outlaws, Notorious Women, and Celebrated Western Actors and Lawmen.