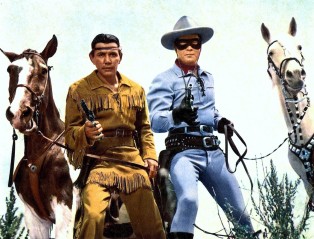

Clayton Moore played the masked cowboy riding high on his horse Silver in the TV favorite The Lone Ranger during the early fifties. With the help of the wise, quiet Indian Tonto, played by Jay Silverheels, the duo went about righting injustices in over one hundred episodes. Moore had the odd fate for an actor of wearing a mask onscreen so that even during the fame of the show, he was hardly recognized. Perhaps for this, there is no other actor who clung to his role do diligently, regularly donning the mask and costume to go out in public, some say even while in his car at a drive-through for fast-food. He was seen wearing his Lone Ranger costume shortly before his death of a heart attack in 1999 at age eighty-five. Silverheels took much less affinity to his role as Tonto and passed away quickly, though coughing laconically, at age sixty in 1980, of pneumonia.

Journal Notes

Following the Necktie Fashion

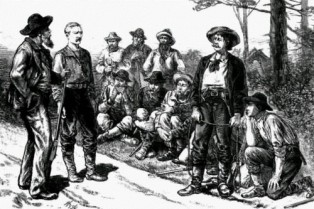

As railroad building brought desperadoes into Wyoming, citizens there found use for many ropes. Several bandits and killers were set swinging in and around Cheyenne and Laramie in 1868. Where the trees were not available, a telegraph pole served for scaffold. That was the case with the stringing up of Dutch Charley at Carbon and George Parrot (“Big Nose George”) at Rawlins. Idaho also attracted horse thieves, stagecoach robbers and killers who had to be eradicated. Vigilance committee at Payette and Boise did this with dispatch. The most notorious man strung up by the Boise group was David Updyke, leader of a desperado gang, who had been able to win an election for sheriff of Ada County. With Updyke and several of his men out of the way, the Idaho crime wave subsided. It’s amazing what happens as a result of a public hanging. Chapter three of The Plea will be on the website next week. Visit www.chrisenss.com.

Sam Sixkiller Outstanding Oklahoma Book Award

|

There’s A Hangin’ Comin’

In Nevada, where highwaymen were active, Egan, Hamilton, Treasure City and other towns organized protective associations with written rules. Aurora formed one in 1864 after about thirty citizens had lost their lives by violence in three years. The vigilantes caught four of the outlaws, built a scaffold in front of the armory and placed four nooses. When the governor heard what was going on and wired an inquiry, the United States marshal replied, “Everything quiet in Aurora. Four men to be hanged in fifteen minutes.” Then, as a crowd watched, the four stretched rope. At Dayton, Carson, Virginia City, and elsewhere, vigilance committees, remained at worked for a decade or longer. In Colorado, outlaws often were sent to the next world in economy-sized packages. Near Sheridan a committee strung four desperadoes from a railroad bridge. On the Denver and Cheyenne road to the north, seven bandits were dropped from another trestle. Denver miners formed a people’s court in 1859 and hanged from a cottonwood a prospector who had killed another for his gold. The next year the same court strung up four killers. The most remembered was James Gordon, who had killed a man for refusing to drink with him at a bar. His hanging was witnessed by several thousand, whom the mounted Jefferson Rangers kept in order. Most of the Colorado mining camps organized people’s courts in the 1860’s. One historian noted that such courts “were about the only ones thoroughly respected and obeyed.” Their proceedings were open and orderly, he said. “They approached the dignity of a regularly constituted tribunal. The prisoner had counsel and could call witnesses if the latter were within reach.

Singing Cowboys

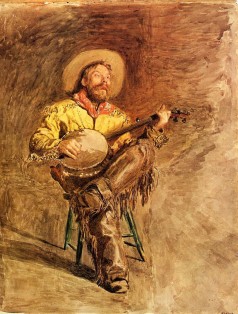

Once in San Antonio, recalls Colonel Jack Potter in Floyd Streeter’s The Kaw, he applied to Ab Blocker for a job. The famous trail boss asked him: “Can you ride a pitching bronc? Can you rope a horse out of the remuda without throwing the loop around your own head? Are you good natured? In case of a stampeded at night, would you drift along in front or circle the cattle to a mills? …Just one more question: can you sing?” As Jack Potter learned to his dismay, the cattle couldn’t stand his singing. Every time he went on guard and san, the cattle would get up and mill around the bed ground. But as soon as Ab Blocker began singing, the cattle commenced to lie down. Potter was fired. Another old-timer , Edward Charles Abbott was more successful. He could not only sing but also make up verses – “anything that came into your head.” He had a hand in composing the Ogallaly Song”, as he tells in We Pointed Them North. This was “just made up as the trail went north by men singing on night guards, with a verse for every river on the trail,” starting form the Nueces in Texas and ending with the Yellowstone in Montana. “When I first heard it it only went as far as Ogallaly on the South Platte, which is why I called it the Ogallaly song.” Considering that so few cowboys could sing and that it wasn’t the quality of the singing that counted – just the reassuring sound of a familiar voice or even a humming or whistling or yodeling – it is a wonder that cowboy songs are as good as they are. As a matter of fact, most cowboy songs, especially cowboy ballads, were written by known cowboy poets, to older tunes. Everyone sing along with me “As I was walking one morning for pleasure, I spied a young cow puncher riding alone, his hat was thrown back and his spurs was a jingling as he approached me a singing this song. Whoop-ee ti-yi-yo, git along little dogies, it’s your misfortune and none of my own. Whoop-ee ti-yi-yo, git along little dogies, for you know Wyoming will be your new home.”

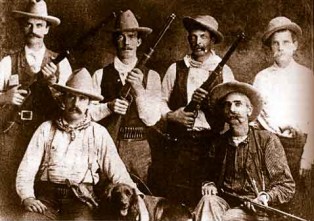

Necktie Parties

In many a mining camp and cattle range, vigilantes did more to drive out desperadoes than did elected officials. The committees of vigilance were formed because there was no other effective action against crime. The vigilance committees of the West differed from the lynchers of the South in that, instead of circumventing the law, they enforced it. They had a large hand in making the frontier communities from anarchy and bridged the gap between lawlessness and the formal administration of justice that came later. Frontiersmen who found a horse thief or two dangling from the limb of a tree did not automatically conclude that justice had been violated. Action by the vigilance committee not only was swifter and surer than that of some of the feeble courts but often was fairer. Proceedings of these committees were informal-more so in some instances than in others. But the committees were organized only after conditions had become desperate, and the men they punished were usually those whose guilt was clear beyond doubt. If this were the Old West I know exactly who I’d like to invite to a necktie party

The American Gold Rush & Seeing the Elephant

This bit of information about the California Gold Rush is for all the students studying this historical event and email me to find out about its significance. From all parts of the United States, from Latin America, and from China, they all flocked to California. Those who made the 18,000-mile sea voyage around South America were called Argonauts. The steamer Californian brought the first 265 into San Francisco Bay on January 28, 1849. Others took a ship to Panama, braved their way across isthmus jungles packed with snakes and mosquitoes, and boarded another boat for San Francisco. Whoever made it to California had “seen the elephant.” Everybody who was hunting for gold, and that was most able-bodied men and a few women, were called 49ers. Instant riches lying everywhere was the definitive image of the gold rush. A “new Eldorado” was waiting a continent away. Just walking by a stream, a person could net $24 worth of gold in a few minutes. The average miner might sock away $1,000 a day. One man found $9,000 in gold after lunch one afternoon. A rainy season greeted the 30,000 gold seekers who came overland in the spring in 1849. An outbreak of cholera claimed 5,000 of the prospectors who worked the fields that year. The town of Marysville recorded 17 murders in one week. One out of every five who came to hunt for gold was dead within six months of his or her arrival. Still, they came in droves. Five hundred shiploads arrived in 1849, filled with dreamers chasing visions of golden nuggets.

More on the American Gold Rush & James Marshall

By 1852, California’s annual gold production reached a high of $81 million. By 1853, the total take was $67 million, and although no one wanted to admit it, the hottest story in the Old West had already peaked. In 1854, a 195-pound mass of gold, the largest known to have been discovered in California, was found at Carson Hill in Calaveras County. In 1859, the famous 54-pound Willard nugget was found at Magalia in Butte County. But for the most part, the rich surface placers were largely exhausted by 1855, and river mining accounted for much of the state’s output until the early 1860s. From the first strike of 1848 through 1855, the total amount of gold taken from the mother lode was right around $350 million. As for the first person involved in the discovery, he did not live happily ever after. After his monumental discovery, Marshall claimed a major chunk of Coloma Valley, but the area was quickly overrun by at least 4,000 would-be gold miners. Marshall found work as a prospector, but he was often hounded by gold rush groupies, men who believed if they stayed close to him he might find some more gold. He continued to be an inactive partner at Sutter’s sawmill until legal difficulties closed it in 1850. In 1857, Marshall returned to Coloma and bought 15 acres of land for $15. He planted a vineyard, dug a cellar, and began bottling California wine. He won a few prizes for his port at county fairs, but taxes and competition found him on the prospecting trail again in the late 1860s. He hit the lecture circuit, but ended up broke in Kansas City. The California legislature took pity on him and passed a $200 a month pension for the discovery of gold in 1872, and then cut it in half the following year. Marshall died forgotten in 1885 and was buried on a hill in Coloma overlooking the gold discovery site. Five years later, a statue was commissioned and placed on his gravesite.

Emigrants West

The Gilded Age was embodied in the private railroad car-a baroque equipage of millionaires that today may be found in museums. But there is little trace of the carriages in which the masses were transported, only the memories of those who rode them. To Robert Louis Stevenson, the emigrant train on which he traveled West in 1879 resembled a series of long wooden boxes-a “Noah’s Ark on wheels.” Wooden benches were their only furniture, “far too short for anyone but a child,” and the atmosphere was stagnant with the smells of food and tobacco. Families and single men and women shared these rolling slums, cooking, washing perfunctorily, and at night sleeping on wooden boards stretched across benches. The rate for these “beds,” which included three straw- (and bug-) filled cushions, was $2.50. Except for rare acts of kindness, the poor emigrants met nothing but rudeness from train functionaries, who even refused to answer their anxious inquiries. “Civility is the main comfort you miss,” Stevenson remarked. “Equality, though very largely conceived in America, does not extend so low down as the emigrant.” I prefer the image of the emigrant as portrayed by William Holden in the movie Arizona. The movie centers around Phoebe Titus a tough, swaggering pioneer woman played by Jean Arthur, but her ways become decidedly more feminine when she falls for California bound Peter Muncie played by William Holden. But Peter won’t be distracted from his journey and Phoebe is left alone and plenty busy with villains Jefferson Carteret and Lazarus Ward plotting at every turn to destroy her freighting company. You just know William Holden will be changing his plans to stay and help Jean out of a jam. The bug Holden describes in the film is decidedly different from the ones emigrants had to sleep with on the way West. One of my favorite lines from the movie are as follows-Holden to Arthur: “I figure it sounds crazy to most people… going to California just to see it. But there’s a gallivanted bug in my blood and that’s the way I am.”

The Gilded Age was embodied in the private railroad car-a baroque equipage of millionaires that today may be found in museums. But there is little trace of the carriages in which the masses were transported, only the memories of those who rode them. To Robert Louis Stevenson, the emigrant train on which he traveled West in 1879 resembled a series of long wooden boxes-a “Noah’s Ark on wheels.” Wooden benches were their only furniture, “far too short for anyone but a child,” and the atmosphere was stagnant with the smells of food and tobacco. Families and single men and women shared these rolling slums, cooking, washing perfunctorily, and at night sleeping on wooden boards stretched across benches. The rate for these “beds,” which included three straw- (and bug-) filled cushions, was $2.50. Except for rare acts of kindness, the poor emigrants met nothing but rudeness from train functionaries, who even refused to answer their anxious inquiries. “Civility is the main comfort you miss,” Stevenson remarked. “Equality, though very largely conceived in America, does not extend so low down as the emigrant.” I prefer the image of the emigrant as portrayed by William Holden in the movie Arizona. The movie centers around Phoebe Titus a tough, swaggering pioneer woman played by Jean Arthur, but her ways become decidedly more feminine when she falls for California bound Peter Muncie played by William Holden. But Peter won’t be distracted from his journey and Phoebe is left alone and plenty busy with villains Jefferson Carteret and Lazarus Ward plotting at every turn to destroy her freighting company. You just know William Holden will be changing his plans to stay and help Jean out of a jam. The bug Holden describes in the film is decidedly different from the ones emigrants had to sleep with on the way West. One of my favorite lines from the movie are as follows-Holden to Arthur: “I figure it sounds crazy to most people… going to California just to see it. But there’s a gallivanted bug in my blood and that’s the way I am.”

Close