Once upon a time in the West, there flourished, according to one frontier editor, “the nearest thing to a universal service company ever invented.” The biggest business in the Old West was so good at what it did that when people swore, they often did so “by God and Wells Fargo.” Seasoned East Coast express men Henry Wells and William G. Fargo began American Express with John Butterfield in 1850. Two years later, they wanted a link with the California gold fields. On March 18, 1852, paper were drawn up organizing Wells, Fargo & Company with initial capital of $300,000 (The comma between the two names was eventually dropped.) Two company representatives opened the first office on San Francisco’s Montgomery Street that July. From the red brick building, a network of routes connected the company with exotic markets such as Hangtown, Yankee Jim, and Poker Flat. The company kept letters flowing between the gold seekers and the folks back home, and it shipped gold back east safely and cheaply. You could even ship people by Wells Fargo. To accomplish these Herculean tasks, Wells Fargo applied cutting-edge 1850s technology. Some shipments, such as the fire engine ordered by the city of Sacramento from a Baltimore manufacturer, were shipped around Cape Horn. But what made Wells Fargo great was its massive fleet of Concord stagecoaches, hand-crafted in New Hampshire, that crisscrossed the Old West with such regularity that their roads often had to be watered to keep down the dust. Cargo was protected by armed guards riding shotgun.

Journal Notes

Walking Wounded

Frontier Visitors

Of all the people who traveled West to see the wild frontier playwright Oscar Wilde was one of the most unique. “To the world I seem, by intention on my part, a dilettante and dandy merely-it is not wise to show one’s heart to the world-and as seriousness of manner is the disguise of the fool, folly in its exquisite modes of triviality and indifference and lack of care is the robe of the wise man. In so vulgar an age as this we all need masks.” So wrote Oscar Wilde in 1894, the year before his crowning achievement, The Importance of Being Earnest, opened in London. And for most of his life the Irish born playwright’s cheerful, witty façade held up quite well. It has held up even better since he died, which probably is why Wilde still regularly shows up on lists of favorite historical dinner guests. But in his last years Wilde was welcome at no tables in England. Though married and the father or two children, Wilde was for years involved with a younger man, Lord Alfred Douglas, called “Bosie,” and he engaged in many anonymous scenes with male prostitutes and pickups. His double life proceeded without incident until soon after Earnest opened, when he received a calling card from Bosie’s eccentric father, the Marquess of Queensbury. It read “To Oscar Wilde, posing as somdominte [sic].” The maintain his mask Wilde felt he had to charge the Maquess with libel. And when the trial began in April 1895, Wilde charmed the jury with punchy testimony. But the Marquess had hired private detectives, and when that evidence began to be presented Wilde abruptly dropped his suit. Later the same day he and Bosie were arrested for immorality. Wilde’s new play continued its successful run, but his name was removed from the program. At his own trial Wilde again maintained his witty upper lip. The first jury could not reach a verdict. But the second jury convicted him, and Wilde was sentenced to two years’ hard labor. He spent the time in solitary confinement, where he was poorly fed and slept on a wooden plank bed. He was put to work sewing mailbags. When he was released in May 1897, Wilde was bankrupt, his manuscripts had either been auctioned or stolen. Friends paid his way to France, where he finally settled in Paris. He wrote a little about prison life, including his famous Ballad of Reading Gaol, and continued to whisk his way through dinner engagements. But he confessed, “I don’t think I shall ever really write again. Something is killed in me.” He picked up boys more frequently than before and began drinking large amounts of absinthe, though doctors had told him it would kill him. Wilde laughed off the warnings, as he did his constant worry about money, quipping, “I am dying beyond my means.” In October 1900, Wilde developed a painful ear infection from an injury he had suffered in prison when he fainted one morning in chapel and perforated an eardrum. Doctors performed surgery, but the infection spread and caused him to develop encephalitis, swelling of the brain. He was taken back to his hotel room, the last in a series of cheaper and cheaper rooms that he could barely afford. The legend is that his last words were “It’s the wallpaper or me-one of us has to go.” But Wilde did not depart with a clever remark. He grew delirious through the month of November. On the thirtieth two close friends near his bed could hear only a painful grinding sound from his throat. A nurse regularly had to dab blood that was drooling from his mount. Slowly his breathing and his pulse weakened until he died at about 2 p.m. that afternoon.

American Gold Rush Song Writer

Forty-niners who trekked across the frontier during the Gold Rush often sang songs written by composer Stephen Foster as they traveled. Foster had a way with sentimental words and catchy melodies that has kept his songs popular for more than a century. There’s something pleasantly wholesome and irresistibly old-fashioned about songs like “Jeannie with the Light Brown Hair” and “Oh! Suzanna.” Two have been adopted by states, “My Old Kentucky Home” and Florida’s “Old Folks at Home” (“Swanee River”). What is ironic is that the composer of such unabashed sentimentality-born on the fiftieth birthday of the nation-ended up so miserably. Foster, who grew up singing but had very little musical training near Pittsburg, was successful almost from his first published songs in 1848. He earned more than $1,000 a year in royalties and married in 1850. But he always spent more than he made and the marriage was unhappy. He wrote fewer songs each year until he left his wife and daughter in 1860 and moved to New York City. There, desperate for cash, he churned out 105 songs-more than half of his entire work-in the last three and a half years of his life. Most were soon forgotten, and his previously lucrative publishing arrangement deteriorated to the point that Foster was selling songs outright for a quick $25. The composer, who drank heavily and suffered symptoms of tuberculosis, grew bitter and lonely as he lived in a series of rooming houses. On January 10, 1864, bedridden with fever, Foster got up to wash himself. Apparently as he stood over the washbasin he fell, shattering the porcelain bowl, which cut his neck deeply. He was found by a chambermaid delivering towels later that day. George Cooper, one of his few friends, was summoned to hear Foster whisper, “I’m done for,” and plead for a drink. Foster was taken to the city-run Bellevue Hospital, where he died, alone and unrecognized, three days later. The hospital, which had registered the 37-year-old composer as Stephen Forster, put his body in the morgue for unknown corpses until Cooper retrieved it. Unlike nearly all that he wrote in his final years, Foster’s last song, which he penned just a few days before he died, joined his earlier classics: Beautiful dreamer, wake unto me. Starlight and dew-drops are waiting for thee. Sounds of the rude world heard in the day, Lull’d by the moonlight have all pass’d away.

American Gold Rush Part 1

Go West, Marx Brothers

This weekend let your troubles “Go West” with the Marx Brothers. Groucho, Chico and Harpo make even “Dead Man’s Gulch” come to life in this film released in 1940. The movie begins with Groucho attempting to fleece Chico and Harpo of the ten dollars he needs to make up the price of a railway ticket and being completely outsmarted. It’s hilarious. The movie contains a Keystone Cops-like chase in which the boys demolish a train in pursuit of the villains. Also funny. Go West features some of Groucho’s best lines. As he’s romancing a saloon girl he says, “Why don’t you let me go? But no, let’s keep this a perfect memory, and someday this bitter ache shall pass, my sweet. Time wounds all heals. You know, there’s a drunk sitting at the first table who looks exactly like you-and one who looks exactly like me. Dull, isn’t it? He’s so full of alcohol, if you put a lighted wick in his mouth, he’d burn for three days. So, let’s go somewhere where we can be alone. Ah, there doesn’t seem to be anyone on this couch.” This was one of the Marx Brothers last films and they only agreed to do Go West because Chico was in trouble. He gambled a lot and needed financial help. Go West helped him get out of debt, but in a short time he was back in the same situation and the brothers had to go to work again. There wasn’t anything the Marx Brothers wouldn’t do for one another.

This weekend let your troubles “Go West” with the Marx Brothers. Groucho, Chico and Harpo make even “Dead Man’s Gulch” come to life in this film released in 1940. The movie begins with Groucho attempting to fleece Chico and Harpo of the ten dollars he needs to make up the price of a railway ticket and being completely outsmarted. It’s hilarious. The movie contains a Keystone Cops-like chase in which the boys demolish a train in pursuit of the villains. Also funny. Go West features some of Groucho’s best lines. As he’s romancing a saloon girl he says, “Why don’t you let me go? But no, let’s keep this a perfect memory, and someday this bitter ache shall pass, my sweet. Time wounds all heals. You know, there’s a drunk sitting at the first table who looks exactly like you-and one who looks exactly like me. Dull, isn’t it? He’s so full of alcohol, if you put a lighted wick in his mouth, he’d burn for three days. So, let’s go somewhere where we can be alone. Ah, there doesn’t seem to be anyone on this couch.” This was one of the Marx Brothers last films and they only agreed to do Go West because Chico was in trouble. He gambled a lot and needed financial help. Go West helped him get out of debt, but in a short time he was back in the same situation and the brothers had to go to work again. There wasn’t anything the Marx Brothers wouldn’t do for one another.

Arizona

There’s nothing more satisfying for me than watching a great western. More often than not criminals in a good western do not die by the hands of the law. They die by the hands of other men. The men they wronged. The outlaws in a great many westerns I watch know they won’t get away. They know they ultimately can’t get away. I once knew a man who committed no crime, but was sentenced to prison because he was persuaded to take a plea. He’d been severely beaten and raped at a penitentiary transfer station. So they put him in a hospital to make him better so that they could make him worse. He was destined to be beaten and raped again. During the eight years he was gone, he collapsed a number of times as a result of Parkinson’s disease, and the doctors put him in the hospital again. He became friends with the nurses and the doctors, and after a while they helped him to get well enough to go back and take more punishment. I saw him after the brutal attacks and he was a broken man. The spirit of the man was gone. The person sitting next to me during the visit with the man said, “This country’s law and their stinking judges! Isn’t anyone going to do something about them?” Staring into the hollow face of the beaten man I once knew as my brother I said, “I don’t want the people who made the law, and I don’t want the people who passed the sentence. The only ones I want to see get theirs are those that falsely accused and caused this pain.” I am convinced that will never really happen. A good western soothes my soul in the midst of the conflict raging in my mind. Last night I enjoyed watching Arizona. Released in 1940, Arizona is more memorable for the thousands of feet of stock footage it provided for other films. For this tale of the development of Arizona, Columbia reconstructed Tucson as the mud-adobe town it had been while the movie’s director, Wesley Ruggles, created set-pieces in the style of De Mille. In one of the movie’s best scenes, the town’s inhabitants watch the Union troops setting light to everything in their wake, as they withdraw. Gary Cooper and Jean Arthur starred in the picture.

There’s nothing more satisfying for me than watching a great western. More often than not criminals in a good western do not die by the hands of the law. They die by the hands of other men. The men they wronged. The outlaws in a great many westerns I watch know they won’t get away. They know they ultimately can’t get away. I once knew a man who committed no crime, but was sentenced to prison because he was persuaded to take a plea. He’d been severely beaten and raped at a penitentiary transfer station. So they put him in a hospital to make him better so that they could make him worse. He was destined to be beaten and raped again. During the eight years he was gone, he collapsed a number of times as a result of Parkinson’s disease, and the doctors put him in the hospital again. He became friends with the nurses and the doctors, and after a while they helped him to get well enough to go back and take more punishment. I saw him after the brutal attacks and he was a broken man. The spirit of the man was gone. The person sitting next to me during the visit with the man said, “This country’s law and their stinking judges! Isn’t anyone going to do something about them?” Staring into the hollow face of the beaten man I once knew as my brother I said, “I don’t want the people who made the law, and I don’t want the people who passed the sentence. The only ones I want to see get theirs are those that falsely accused and caused this pain.” I am convinced that will never really happen. A good western soothes my soul in the midst of the conflict raging in my mind. Last night I enjoyed watching Arizona. Released in 1940, Arizona is more memorable for the thousands of feet of stock footage it provided for other films. For this tale of the development of Arizona, Columbia reconstructed Tucson as the mud-adobe town it had been while the movie’s director, Wesley Ruggles, created set-pieces in the style of De Mille. In one of the movie’s best scenes, the town’s inhabitants watch the Union troops setting light to everything in their wake, as they withdraw. Gary Cooper and Jean Arthur starred in the picture.

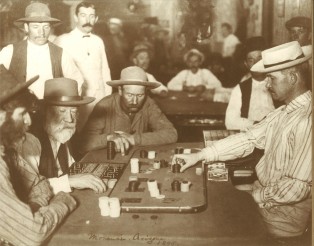

Gambling

American’s oldest diversion deteriorated into a vice. In the turn of a card or the roll of a dice for all or nothing, there was a kind of daring that touched the American spirit. “The lust for work is matched…by the lust to gamble.” The affluent risked thousands of comforts; the poor risked bread money on gaming tables in slum taverns. The gambling fever produced two opposing species. First were the predatory card sharps and confidence men who understood human weakness and how to exploit it; second were the masses, eternally gullible to the lure of something for nothing. Throughout the nation these adversaries met-in lotteries, over tables, at racetracks, in casinos, cockpits-and the result was nearly always the same. The suckers lost. In 1890, San Francisco had an estimated 2500 illegal gambling houses, which produced, as they did elsewhere, crime and degeneracy. And while these are hardly the by-products one would expect of a leisure activity, it should be remembered that vice can become a pastime for people who had little alternative resource. Starting with the Gold Rush era, the West from the Rio Grande to Canadian border knew no way to spend free hours except gambling. Judge or laborer, clergyman or clerk, all elbowed their way into the gambling tents.

American’s oldest diversion deteriorated into a vice. In the turn of a card or the roll of a dice for all or nothing, there was a kind of daring that touched the American spirit. “The lust for work is matched…by the lust to gamble.” The affluent risked thousands of comforts; the poor risked bread money on gaming tables in slum taverns. The gambling fever produced two opposing species. First were the predatory card sharps and confidence men who understood human weakness and how to exploit it; second were the masses, eternally gullible to the lure of something for nothing. Throughout the nation these adversaries met-in lotteries, over tables, at racetracks, in casinos, cockpits-and the result was nearly always the same. The suckers lost. In 1890, San Francisco had an estimated 2500 illegal gambling houses, which produced, as they did elsewhere, crime and degeneracy. And while these are hardly the by-products one would expect of a leisure activity, it should be remembered that vice can become a pastime for people who had little alternative resource. Starting with the Gold Rush era, the West from the Rio Grande to Canadian border knew no way to spend free hours except gambling. Judge or laborer, clergyman or clerk, all elbowed their way into the gambling tents.

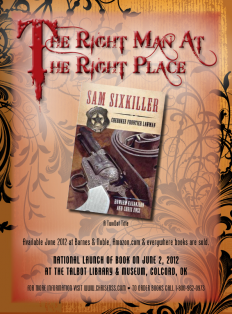

The Lawman & the Six-Shooter

Old West partners to reckon with…Cherokee Lawman Sam Sixkiller and a six-shooter. Besides being a US deputy marshal, Sixkiller was a detective for the Missouri Pacific Railroad and in 1880 became the first captain of the US Indian Police (USIP), which was headquartered at Muskogee, Creek Nation. The USIP served under the Indian agent for the Five Civilized Tribes. Sam Sixkiller came out of this milieu of politics, crime, and upheaval and brought a sense of justice and fairness to the people who lived in the Cherokee Nation and the Indian Territory. Sixkiller became widely known and praised for his law enforcement skills, commitment, and understanding of duty to the job. The Oklahoma Historical Society plans to present its Outstanding Book on Oklahoma History (published in 2012) to Globe Pequot Press and Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss, publisher and authors of Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman during our Annual Awards Luncheon on April 19, 2013. For more information about the book Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman visit www.chrisenss.com.

Old West partners to reckon with…Cherokee Lawman Sam Sixkiller and a six-shooter. Besides being a US deputy marshal, Sixkiller was a detective for the Missouri Pacific Railroad and in 1880 became the first captain of the US Indian Police (USIP), which was headquartered at Muskogee, Creek Nation. The USIP served under the Indian agent for the Five Civilized Tribes. Sam Sixkiller came out of this milieu of politics, crime, and upheaval and brought a sense of justice and fairness to the people who lived in the Cherokee Nation and the Indian Territory. Sixkiller became widely known and praised for his law enforcement skills, commitment, and understanding of duty to the job. The Oklahoma Historical Society plans to present its Outstanding Book on Oklahoma History (published in 2012) to Globe Pequot Press and Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss, publisher and authors of Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman during our Annual Awards Luncheon on April 19, 2013. For more information about the book Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontier Lawman visit www.chrisenss.com.

The Adventures of Deadwood Dick

Another great Old West partnership -Nat Love and roping. Nat Love (1854-1921) was born to slave parents on the Robert Love plantation in Davidson County, Tennessee. He was freed at the end of the Civil War, just after he turned eleven. At fifteen, he found a task he enjoyed, taming colts for a dime a head. Fortune smiled with a $100 raffle win, giving him enough bucks to split the winnings with his mother and head west. Outside Dodge City, after a wild audition on the back of a foul-tempered bronco called Good Eye, Love found work with the Duval cattle outfit from Texas. For three years, he was based in the Texas panhandle near the Palo Dura River. In 1872, he was in Arizona’s Gila River country working for Pete Gallinger as the resident authority on reading brands. In 1876, Love’s outfit received an order for 2,000 longhorns to be delivered to Deadwood in Dakota Territory. In Deadwood on the 4th of July, Love won a mustang roping contest and a shooting match. In addition to the prize money, the excited residents bestowed upon him the title of Deadwood Dick. In a time when men were known by their buckskin nicknames – Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill, Texas Jack – Love saw his dubbing as a badge of honor. Back in the Southwest, his party was attacked by warriors. Wounded in the leg, he passed out, only to awake in the camp of Yellow Dog. According to Love, he was told he was “too brave to die” and plans were made to adopt him. His ears were pierced with a bone from a deer’s leg. He was designated to marry Buffalo Papoose, daughter of the chief. A month later, with the wedding fast approaching, Love stole a pony and skipped out of camp. Twelve hours and one hundred miles later, he was back at the ranch. Meanwhile, in wild and woolly New York, author Edward Lytton Wheeler was finishing up a story for dime novel publisher Beadle and Adams. Wheeler had never been west of Pennsylvania, but on October 15, 1877, Deadwood Dick, the Prince of the Road; or the Black Rider of the Black Hills was published. Over the next eight years, Wheeler penned thirty-three Deadwood Dick novels, as well as a play, Deadwood Dick, A Road Agent, A Drama of the Gold Mines. The stories were so popular that faux Deadwood Dicks began crawling out of the woodwork. For more information about Beadle and Adams Dime Novels read The Raftsman’s Daughter by yours truly.

Another great Old West partnership -Nat Love and roping. Nat Love (1854-1921) was born to slave parents on the Robert Love plantation in Davidson County, Tennessee. He was freed at the end of the Civil War, just after he turned eleven. At fifteen, he found a task he enjoyed, taming colts for a dime a head. Fortune smiled with a $100 raffle win, giving him enough bucks to split the winnings with his mother and head west. Outside Dodge City, after a wild audition on the back of a foul-tempered bronco called Good Eye, Love found work with the Duval cattle outfit from Texas. For three years, he was based in the Texas panhandle near the Palo Dura River. In 1872, he was in Arizona’s Gila River country working for Pete Gallinger as the resident authority on reading brands. In 1876, Love’s outfit received an order for 2,000 longhorns to be delivered to Deadwood in Dakota Territory. In Deadwood on the 4th of July, Love won a mustang roping contest and a shooting match. In addition to the prize money, the excited residents bestowed upon him the title of Deadwood Dick. In a time when men were known by their buckskin nicknames – Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill, Texas Jack – Love saw his dubbing as a badge of honor. Back in the Southwest, his party was attacked by warriors. Wounded in the leg, he passed out, only to awake in the camp of Yellow Dog. According to Love, he was told he was “too brave to die” and plans were made to adopt him. His ears were pierced with a bone from a deer’s leg. He was designated to marry Buffalo Papoose, daughter of the chief. A month later, with the wedding fast approaching, Love stole a pony and skipped out of camp. Twelve hours and one hundred miles later, he was back at the ranch. Meanwhile, in wild and woolly New York, author Edward Lytton Wheeler was finishing up a story for dime novel publisher Beadle and Adams. Wheeler had never been west of Pennsylvania, but on October 15, 1877, Deadwood Dick, the Prince of the Road; or the Black Rider of the Black Hills was published. Over the next eight years, Wheeler penned thirty-three Deadwood Dick novels, as well as a play, Deadwood Dick, A Road Agent, A Drama of the Gold Mines. The stories were so popular that faux Deadwood Dicks began crawling out of the woodwork. For more information about Beadle and Adams Dime Novels read The Raftsman’s Daughter by yours truly.