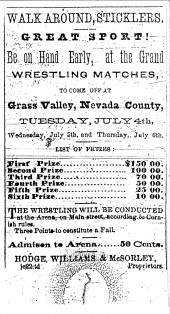

Spelling bees, Saturday night shoot-‘em-ups, quilting parties, and card games were just a few ways in which people amused themselves in the Old West. Wrestling matches were among the most favorite past-times. Early colonists from England are credited with making the sport popular. They brought with them a variety of wrestling styles and often persuaded Native Americans to participate in the matches. Wrestling tournaments were featured at picnics, threshing bees, and holiday celebrations. Professional wrestlers from carnivals would often times challenge local wrestling champions to a match and cash prizes were awarded to the amateur that could throw the expert. These events were so well attended special arenas were built to hold the crowds that flocked to see them. On nights when no one would challenge the wrestling champ, a large, brown bear was paraded out for him to compete against. If the man won he was awarded more than a hundred dollars. If the bear won he got a basket of apples.

Spelling bees, Saturday night shoot-‘em-ups, quilting parties, and card games were just a few ways in which people amused themselves in the Old West. Wrestling matches were among the most favorite past-times. Early colonists from England are credited with making the sport popular. They brought with them a variety of wrestling styles and often persuaded Native Americans to participate in the matches. Wrestling tournaments were featured at picnics, threshing bees, and holiday celebrations. Professional wrestlers from carnivals would often times challenge local wrestling champions to a match and cash prizes were awarded to the amateur that could throw the expert. These events were so well attended special arenas were built to hold the crowds that flocked to see them. On nights when no one would challenge the wrestling champ, a large, brown bear was paraded out for him to compete against. If the man won he was awarded more than a hundred dollars. If the bear won he got a basket of apples.

Journal Notes

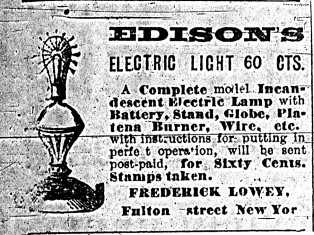

Edison’s Effective Lamp

Early settlers had more than one way to light up their log cabins. Candles, kerosene, and lard-oil lamps were among the few. These types of lights were a fire hazard and in many cases were responsible for entire towns being burnt down. A safer way to provide light to homes was being sought in England. Sir Humphrey Davy was working on producing electric arcs using a platinum wire incandescent and passing a current through the air. By 1840 a number of incandescent lamps, including Davy’s, were being patented, but none were commercially successful until American inventor Thomas Alva Edison produced his carbon filament lamp in 1879. Edison’s electric light was a much sought after product. It worked by passing a weak electric current between a heated filament and a cold electrode. The first power station was constructed on Pearl Street in New York. In 1882 several miles of streets were dug up to install electric cables from the station to surrounding homes, which began receiving electric current on September 4. Electric lighting didn’t dominate the Old West until the end of the century.

Early settlers had more than one way to light up their log cabins. Candles, kerosene, and lard-oil lamps were among the few. These types of lights were a fire hazard and in many cases were responsible for entire towns being burnt down. A safer way to provide light to homes was being sought in England. Sir Humphrey Davy was working on producing electric arcs using a platinum wire incandescent and passing a current through the air. By 1840 a number of incandescent lamps, including Davy’s, were being patented, but none were commercially successful until American inventor Thomas Alva Edison produced his carbon filament lamp in 1879. Edison’s electric light was a much sought after product. It worked by passing a weak electric current between a heated filament and a cold electrode. The first power station was constructed on Pearl Street in New York. In 1882 several miles of streets were dug up to install electric cables from the station to surrounding homes, which began receiving electric current on September 4. Electric lighting didn’t dominate the Old West until the end of the century.

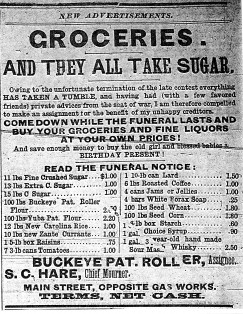

In Need of Provisions

The western pioneer was independent only until the supplies in his covered wagon ran out. They looked to stores to supply them with goods necessary for life and desirable for comfort. The local market was the place to get powder and shot, tobacco, coffee, clothing, beans, liquor and news. Specialty shops provided pioneers with wallpaper, stationary, crayons, stereoscopic views, beauty cream and other refinements not usually associated with life on the plains. The general store was the place of first resort for everything from coal oil to calico to canned oysters, and much more. The place smelled of just about everything; the rich fruitiness of plug tobacco, the leather of boots and belts, fresh ground coffee, cheese, dried and pickled fish and the subtle musty-sweet tang of fresh fabric in bolts. Not an inch of space was wasted.

The western pioneer was independent only until the supplies in his covered wagon ran out. They looked to stores to supply them with goods necessary for life and desirable for comfort. The local market was the place to get powder and shot, tobacco, coffee, clothing, beans, liquor and news. Specialty shops provided pioneers with wallpaper, stationary, crayons, stereoscopic views, beauty cream and other refinements not usually associated with life on the plains. The general store was the place of first resort for everything from coal oil to calico to canned oysters, and much more. The place smelled of just about everything; the rich fruitiness of plug tobacco, the leather of boots and belts, fresh ground coffee, cheese, dried and pickled fish and the subtle musty-sweet tang of fresh fabric in bolts. Not an inch of space was wasted.

Take the Stage

I’ll be speaking at the Nevada County Historical Society meeting tomorrow evening at 6:30 p.m. at the Madelyn Helling Library in Nevada City. The talk will center on the most recent book released The Bedside Book of Bad Girls: Outlaw Women of the Midwest. Email me for more information – gvcenss@aol.com. Hope to see you there. And now for this commercial message…. The stagecoach figured prominently in the early west. Under ideal condition, a coach driven by a fresh team of horses could “cut dirt” at the breakneck pace of nine miles per hour. Yet driving condition throughout much of the century were rarely ideal. Vehicles got stuck in ruts of mud so often that the expression “up to the hub” became a national colloquialism to illustrate any intractable predicament. Bad roads and driver impatience frequently combined to turn a coach over. During any long stage trip, in fact, passengers expected and were mentally prepared for at least one turnover.

I’ll be speaking at the Nevada County Historical Society meeting tomorrow evening at 6:30 p.m. at the Madelyn Helling Library in Nevada City. The talk will center on the most recent book released The Bedside Book of Bad Girls: Outlaw Women of the Midwest. Email me for more information – gvcenss@aol.com. Hope to see you there. And now for this commercial message…. The stagecoach figured prominently in the early west. Under ideal condition, a coach driven by a fresh team of horses could “cut dirt” at the breakneck pace of nine miles per hour. Yet driving condition throughout much of the century were rarely ideal. Vehicles got stuck in ruts of mud so often that the expression “up to the hub” became a national colloquialism to illustrate any intractable predicament. Bad roads and driver impatience frequently combined to turn a coach over. During any long stage trip, in fact, passengers expected and were mentally prepared for at least one turnover.

More About Old West Ads

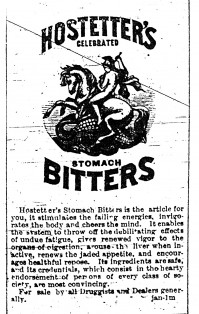

For those who might be feeling as poorly as a centipede with sciatic rheumatism the following Old West advertisement might just be the thing to make it better. In the early 19th century most Americans healed themselves as their ancestors had for centuries. Professional medical assistance was either too far away, to expensive, or both. Even wealthy urban families usually attempted some sort of home health care before the doctor was called. This care was usually administered with the aid of books, pamphlets, and proprietary medicines purchased at the general store. Proprietary medicine advertisements were the mainstay of newspapers in the Old West. Newspapers carried notices for medicated vapor baths, artificial teeth, genuine Galvanic Rings, the Anodyne Necklace and other amulets. Some patent medicine companies spent more than $100,000 a year advertising their products. Patent medicines were the hottest-selling items on store shelves. If the labels on the medicines were to be believed, they could handle just about any and ever complaint. One concoction grandly promised to cure thirty different disorders including “nervous debility caused by the indiscretions of youth.” Mostly they relied on a heavy lacing of alcohol to work their proclaimed wonders. Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters, for instance, soothed indigestion with a formula packing a fifty-proof wallop.

For those who might be feeling as poorly as a centipede with sciatic rheumatism the following Old West advertisement might just be the thing to make it better. In the early 19th century most Americans healed themselves as their ancestors had for centuries. Professional medical assistance was either too far away, to expensive, or both. Even wealthy urban families usually attempted some sort of home health care before the doctor was called. This care was usually administered with the aid of books, pamphlets, and proprietary medicines purchased at the general store. Proprietary medicine advertisements were the mainstay of newspapers in the Old West. Newspapers carried notices for medicated vapor baths, artificial teeth, genuine Galvanic Rings, the Anodyne Necklace and other amulets. Some patent medicine companies spent more than $100,000 a year advertising their products. Patent medicines were the hottest-selling items on store shelves. If the labels on the medicines were to be believed, they could handle just about any and ever complaint. One concoction grandly promised to cure thirty different disorders including “nervous debility caused by the indiscretions of youth.” Mostly they relied on a heavy lacing of alcohol to work their proclaimed wonders. Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters, for instance, soothed indigestion with a formula packing a fifty-proof wallop.

Absolutely Pure

Around the House

A one-room log cabin with dirt or puncheon floor, simple fireplace, sawbuck table and straw mattress in which an entire family might sleep – that was as far as luxury went on the frontier and in newly settled regions of the country. Long-settled communities enjoyed roomier abodes, of course, and as the wealth of the region and of the nation grew, houses became larger, more elaborate and better equipped. Specialized stores helped homeowners furnish their dwellings with the most fashionable sofas, chairs, and love-seats available. Early Victorian furniture was popular and the most common style carried by furniture stores. Victorian furniture was large and made of mahogany, rosewood or black walnut. Notable characteristics were saber legs; marble table tops; turned bedposts; mushroom-turned wooden knobs for handles; ornamentation in the form of carved medallions featuring flowers, fruits and foliage. There’s nothing simple about that look. I’m not surprised the advertisment boasted that the items were cheap.

A one-room log cabin with dirt or puncheon floor, simple fireplace, sawbuck table and straw mattress in which an entire family might sleep – that was as far as luxury went on the frontier and in newly settled regions of the country. Long-settled communities enjoyed roomier abodes, of course, and as the wealth of the region and of the nation grew, houses became larger, more elaborate and better equipped. Specialized stores helped homeowners furnish their dwellings with the most fashionable sofas, chairs, and love-seats available. Early Victorian furniture was popular and the most common style carried by furniture stores. Victorian furniture was large and made of mahogany, rosewood or black walnut. Notable characteristics were saber legs; marble table tops; turned bedposts; mushroom-turned wooden knobs for handles; ornamentation in the form of carved medallions featuring flowers, fruits and foliage. There’s nothing simple about that look. I’m not surprised the advertisment boasted that the items were cheap.

Old West Advertisement

The Passing of Harry Carey, Jr.

Boot Hill

Usually, a bad man was buried unceremoniously in a local “boot hill,” so called because most of those who were buried therein died with their boots on, and were even buried with them on. However, some had funerals; and tombstones with epitaphs marked their graves for some time, usually until souvenir hunters demolished them. On Sam Bass’ tombstone was engraved, “A brave man reposes in death here. Why was he not true?” On Seaborne Barnes’ gravestone was written, “He was right bower (meaning he was an anchor) to Sam Bass.” Besides his name and dates, Cole Younger’s tombstone had the words, “Rest in Peace, Our Dear Beloved.” Perhaps Jesse James’s complete epitaph should be given: “In Loving Remembrance of My Beloved Son, Jesse W. James, Died April 3, 1882, Aged 36 Years, 6 Months, 28 Days Murdered by a Traitor and Coward Whose Name is Not Worthy to Appear Here.” (I think I’ll have something like that inscribed on my brother’s tombstone.) The coward referred to was Bob Ford who, as you recall, shot Jesse in the back while he was hanging a picture on the wall, very unusually unarmed. Other than biographical information, Langford Peel’s tombstone bore the inscriptions: “In Life, Beloved by his Friends, and Respected by his Enemies. Vengeance is Mine, Saith the Lord, I Know That My Redeemer Liveth. Erected by a Friend.” Most unusual of the epitaphs of bad men was that of Lame Johnny, a man who never knew when to keep his mouth shut, hanged by impromptu vigilantes and award the epitaph: “Lame Johnny, Stranger, pass gently o’er this sod. If he opens his mouth, you’re gone, by God.”

Usually, a bad man was buried unceremoniously in a local “boot hill,” so called because most of those who were buried therein died with their boots on, and were even buried with them on. However, some had funerals; and tombstones with epitaphs marked their graves for some time, usually until souvenir hunters demolished them. On Sam Bass’ tombstone was engraved, “A brave man reposes in death here. Why was he not true?” On Seaborne Barnes’ gravestone was written, “He was right bower (meaning he was an anchor) to Sam Bass.” Besides his name and dates, Cole Younger’s tombstone had the words, “Rest in Peace, Our Dear Beloved.” Perhaps Jesse James’s complete epitaph should be given: “In Loving Remembrance of My Beloved Son, Jesse W. James, Died April 3, 1882, Aged 36 Years, 6 Months, 28 Days Murdered by a Traitor and Coward Whose Name is Not Worthy to Appear Here.” (I think I’ll have something like that inscribed on my brother’s tombstone.) The coward referred to was Bob Ford who, as you recall, shot Jesse in the back while he was hanging a picture on the wall, very unusually unarmed. Other than biographical information, Langford Peel’s tombstone bore the inscriptions: “In Life, Beloved by his Friends, and Respected by his Enemies. Vengeance is Mine, Saith the Lord, I Know That My Redeemer Liveth. Erected by a Friend.” Most unusual of the epitaphs of bad men was that of Lame Johnny, a man who never knew when to keep his mouth shut, hanged by impromptu vigilantes and award the epitaph: “Lame Johnny, Stranger, pass gently o’er this sod. If he opens his mouth, you’re gone, by God.”