Old West cowboys looking for a job driving cattle across the plains were generally asked the following question. “Can you ride a pitching bronc? Can you rope a horse out of the remuda without throwing the loop around your own head? Are you good-natured? In the case of a stampede at night, would you drift along in front or circle the cattle to a mill? Just one more question: can you sing? Some cowboys could not. Every time they went on guard and sang, the cattle would get up and mill around the bed ground. Good cowboy singers would have to be called in to serenade the animals. The cattle would quickly lie down when they sang. Considering that so few cowboys could sing and that it wasn’t the quality of the singing that counted-just the reassuring sound of a familiar voice or even a humming or whistling or yodeling-it’s a wonder that cowboy songs are as good as they are. As a matter of fact, most cowboy songs, especially cowboy ballads, were written by known (if forgotten) cowboy poets, to older tuners. Except as they help to soothe restless cattle or to keep them moving, cowboy songs are not true work songs like sailor’s chanteys. They are more like lumberjack songs-occupational and recreational songs-in which men sing about their work and play and express certain occupational attitude. Cowboy songs have the freedom, casualness and uncomplicated quality of cowboy’s life. Because the cowboy’s subjects are so few and basic, he has mastered them and can handle them simply and sincerely. As the Chisholm Trail from Texas to Kansas was the classic cattle trail, so the song that takes its name from the trail is the classic trail song. The easy swing of the tune is deceptive considering the cowboy’s troubles on the trail-weather, food, boss, pay. Here are a few verses from the song The Old Chisholm Trail. “I wake in the mornin’ afore daylight and afore I sleep the moon shines bright. Oh it’s bacon and beans most every day; I’d as soon be a-eatin prairie hay. With my knees in the saddle and my seat in the sky, I’ll quit punchin’ cows in the sweet by and by.” I bet Roy Rogers could have lulled a herd of cattle into a coma with his voice. Ride on, Roy.

Journal Notes

A Cowboys Neckerchief

A useful part of the cowboy’s costume was his neckerchief, or “wipes” as he called it. Neckerchiefs were usually red or blue, like the old bandana of the South, or black silk which did not show the dirt. The rodeo rider of modern days goes in for bright colors. Rangemen usually wished to avoid colors which attracted attention. An inconspicuous rider was more apt to catch a rustler. Usually the cowboy wore his neck scarf draped loosely over his chest with the knot in the back. If the sun shone on his back he reversed the scarf to protect his neck. When riding in the drag of a herd he pulled it up over mouth and nose to keep out the dust. In winter he might put it over his eyes to prevent snow blindness or to protect his face from icy winds and stinging sleet. He could use it to tie down his hat, to serve as an ear muff in cold weather, or to keep his head cool on a blazing summer day by wearing it, wet, under his hat. When he washed his face in the morning, an ever ready towel was hanging from his neck. In his work he had this handy mop to wipe the sweat off his face. He could use it for holding the handle of a hot branding iron, for a blindfold on a snaky horse, or as a “pigging string,” that is, a string for tying a roped animal by all four feet the way a hog is tied. Likewise the neckerchief could be used as a makeshift hobble for his horse, a tourniquet a sling for a broken arm, or a bandage. In the movie Appaloosa with Ed Harris and Vigo Mortensen, Mortensen’s character demonstrates just how important the neckerchief was to cowboys. In one scene he is carefully mending a tear in the garment. In addition to all these great uses I’ve found that the neckerchief is perfect for covering unsightly turkey neck.

A useful part of the cowboy’s costume was his neckerchief, or “wipes” as he called it. Neckerchiefs were usually red or blue, like the old bandana of the South, or black silk which did not show the dirt. The rodeo rider of modern days goes in for bright colors. Rangemen usually wished to avoid colors which attracted attention. An inconspicuous rider was more apt to catch a rustler. Usually the cowboy wore his neck scarf draped loosely over his chest with the knot in the back. If the sun shone on his back he reversed the scarf to protect his neck. When riding in the drag of a herd he pulled it up over mouth and nose to keep out the dust. In winter he might put it over his eyes to prevent snow blindness or to protect his face from icy winds and stinging sleet. He could use it to tie down his hat, to serve as an ear muff in cold weather, or to keep his head cool on a blazing summer day by wearing it, wet, under his hat. When he washed his face in the morning, an ever ready towel was hanging from his neck. In his work he had this handy mop to wipe the sweat off his face. He could use it for holding the handle of a hot branding iron, for a blindfold on a snaky horse, or as a “pigging string,” that is, a string for tying a roped animal by all four feet the way a hog is tied. Likewise the neckerchief could be used as a makeshift hobble for his horse, a tourniquet a sling for a broken arm, or a bandage. In the movie Appaloosa with Ed Harris and Vigo Mortensen, Mortensen’s character demonstrates just how important the neckerchief was to cowboys. In one scene he is carefully mending a tear in the garment. In addition to all these great uses I’ve found that the neckerchief is perfect for covering unsightly turkey neck.

Marshal Tom Smith

Several Kansas cow towns produced the West’s best known frontier marshals. Of these by far the most courageous was the one who had the shortest career. Thomas James Smith, the marshal of Abilene during its boom days as the original terminus of the Chisholm Trail. Tom Smith, more than any other, exemplified western fiction writer William MacLeod Raine’s (Raine is one of my favorite authors) description of frontier peace officers: “They usually were quiet men. They served fearlessly and with inadequate reward. Their resort to the six-shooter was always in reluctant self-defense. Early in the cattle season of 1870, Abilene had tried several marshals, but no one had lasted more than a few weeks. Finally, on June 4, the town trustees hired Tom Smith, a husky Irishman who had grown up in New York and been a successful marshal in Wyoming. His pay was $150 a month. One of his jobs was to enforce the ban on carrying firearms. Notices of this edict had been posted in public places, but cowhands from Texas had shot them full of holes. On Smith’s first Saturday night in Abilene, a town rowdy, known as Big Hank, decided to show up the new marshal. With his six-shooter in his belt, Hank swaggered up to Smith and begun to taunt him. “Are you the man who thinks he is going to run this town?” he asked. “I’ve been hired as marshal,” replied the officer. “I’m going to keep order and enforce the law.” “What are you going to do about the gun ordinance?” the bully inquired. “I’m going to see that it’s obeyed-and I’ll trouble you to hand me your pistol now.” With an oath, Big Hank refused. Smith sprang forward and felled him with a single blow on the jaw. Then he took the ruffian’s gun and ordered him to leave town at once-and permanently. Hank slipped out quickly, glad to escape the jibes of the street crowd. The new marshal’s first action impressed those who saw it, and news of what had happened spread to the cow camps on the prairies. In one camp on a branch of Chapman Creek, a braggart called Wyoming Frank bet that he could go into Abilene and wear his six-shooter. He rode in on Sunday morning and had a few drinks before Smith appeared. When Frank saw the marshal walking down the middle of the street, he went out and tried to engage him in a quarrel. Smith’s only answer was a request for the bully’s gun, which was refused. Smith, with steel in his eyes, advance toward Frank. The ruffian backed away, sidling through the swinging doors of a saloon where a crowd had gathered to see what might happen. Smith followed him inside and when Frank again refused to hand over his gun, the marshal pounced on him. With two swift blows, Smith knocked him to the floor, then took the gun and gave Frank five minutes to leave Abilene. The action so astonished the men in the saloon that, for a moment, they stood speechless. Then the shopkeeper handed Smith his gun and said, “That was the nerviest act I ever saw. You did you duty, and the coward got what he deserved. Here’s my gun. I reckon I’ll not need it as long as you’re marshal.” Others came forward offering their six-shooters. The marshal told them to leave the pistols with the bartender until they were ready to go back to their camps. Smith, who often rode up and down the streets on his gray horse, Silverheels, kept order so well that the town trustees raised his pay to $225 a month and gave him an assistant. He stayed on the job, without wasting any time drinking or gambling; and found no need to kill anyone, but with peace restored and the cowboys gone until next year’s drive, his job was discontinued.

Several Kansas cow towns produced the West’s best known frontier marshals. Of these by far the most courageous was the one who had the shortest career. Thomas James Smith, the marshal of Abilene during its boom days as the original terminus of the Chisholm Trail. Tom Smith, more than any other, exemplified western fiction writer William MacLeod Raine’s (Raine is one of my favorite authors) description of frontier peace officers: “They usually were quiet men. They served fearlessly and with inadequate reward. Their resort to the six-shooter was always in reluctant self-defense. Early in the cattle season of 1870, Abilene had tried several marshals, but no one had lasted more than a few weeks. Finally, on June 4, the town trustees hired Tom Smith, a husky Irishman who had grown up in New York and been a successful marshal in Wyoming. His pay was $150 a month. One of his jobs was to enforce the ban on carrying firearms. Notices of this edict had been posted in public places, but cowhands from Texas had shot them full of holes. On Smith’s first Saturday night in Abilene, a town rowdy, known as Big Hank, decided to show up the new marshal. With his six-shooter in his belt, Hank swaggered up to Smith and begun to taunt him. “Are you the man who thinks he is going to run this town?” he asked. “I’ve been hired as marshal,” replied the officer. “I’m going to keep order and enforce the law.” “What are you going to do about the gun ordinance?” the bully inquired. “I’m going to see that it’s obeyed-and I’ll trouble you to hand me your pistol now.” With an oath, Big Hank refused. Smith sprang forward and felled him with a single blow on the jaw. Then he took the ruffian’s gun and ordered him to leave town at once-and permanently. Hank slipped out quickly, glad to escape the jibes of the street crowd. The new marshal’s first action impressed those who saw it, and news of what had happened spread to the cow camps on the prairies. In one camp on a branch of Chapman Creek, a braggart called Wyoming Frank bet that he could go into Abilene and wear his six-shooter. He rode in on Sunday morning and had a few drinks before Smith appeared. When Frank saw the marshal walking down the middle of the street, he went out and tried to engage him in a quarrel. Smith’s only answer was a request for the bully’s gun, which was refused. Smith, with steel in his eyes, advance toward Frank. The ruffian backed away, sidling through the swinging doors of a saloon where a crowd had gathered to see what might happen. Smith followed him inside and when Frank again refused to hand over his gun, the marshal pounced on him. With two swift blows, Smith knocked him to the floor, then took the gun and gave Frank five minutes to leave Abilene. The action so astonished the men in the saloon that, for a moment, they stood speechless. Then the shopkeeper handed Smith his gun and said, “That was the nerviest act I ever saw. You did you duty, and the coward got what he deserved. Here’s my gun. I reckon I’ll not need it as long as you’re marshal.” Others came forward offering their six-shooters. The marshal told them to leave the pistols with the bartender until they were ready to go back to their camps. Smith, who often rode up and down the streets on his gray horse, Silverheels, kept order so well that the town trustees raised his pay to $225 a month and gave him an assistant. He stayed on the job, without wasting any time drinking or gambling; and found no need to kill anyone, but with peace restored and the cowboys gone until next year’s drive, his job was discontinued.

Hang Them All

Federal judges, free from local politics, (and you certainly won’t find one like that in Kansas City, Missouri) were especially influential in making courts effective on the frontier. Outstanding was Isaac Charles Parker, known as the Hanging Judge. His court at Fort Smith Arkansas, had jurisdiction over the wild Indian Territory, where outlaws of several races terrorized large sections of country, robbing and killing with little concern for the law. Ohio-born Parker had been a Missouri judge and congressman. When he assumed his duties at Fort Smith in 1875, he was, at thirty-six, the youngest man on the federal bench. He took his new duties seriously. In his first court term, he tried ninety-one criminals. Of eighteen murder cases, fifteen ended in conviction. Of eight killers sentenced to be hanged, one was killed while trying to escape and another had his sentence commuted to life in prison, and the other six were hanged in public on September 3, as several thousand watched. Most people approved of the new judge. “The certainty of punishment is the only sure prevention of crime,” said Fort Smith’s Western Independent, “and the administration of the laws by Judge Parker has made him a terror to all evildoers in the Indian country.” During the twenty-one years in which he presided over the court, Judge Parker lost sixty-five deputy marshals, killed while trying to perform their duties. He tried more than thirteen thousand crimes that carried the death penalty; he sentenced 172 to be hanged. Some escaped the noose by dying in jail or by obtaining commutation or presidential reprieve, but 88 swung from the gallows outside of his jail. By the time of Judge Parker’s death, late in 1896, most of the West had been tamed. Feuds, range wars and vigilante hangings were less common. Such primitive means of attaining justice had given way to the application of statutory law through the courts. Except for sporadic outbreaks, the West had become almost as law-abiding as the rest of the country.

Outside the Law

Several bandits of Mexican outlaws included members who were dispossessed miners. In the two years following the passage of the California tax law, these thieves maintained an intensive program of horse stealing, running off cattle, holding up stagecoaches, robbing saloons and stores. Nobody knew who was in these bands, but when their depredations occurred hundreds of miles apart people came to the conclusion that there were at least five bands. The name of the leader of each was said to be Joaquin-a common Mexican name-and it is noticeable that no surnames were mentions. In fact, no one knew any of the bandits’ names. Outlawry became so frequent that, in the spring of 1853, a bill was introduced in the California legislature offering a reward for the head of “Joaquin,” no last name given. It was pointed out that a law putting a price on the head of a man who was unknown except by the popular sobriquet, “Joaquin,” would be unconstitutional, and the bill failed to pass. However, the legislature did authorize a former Texan, Harry Love, to raise a small company of mounted rangers to capture the “robbers commanded by the five Joaquins.” Governor John Bigler, on his own authority, offered a reward of $1,500 for any Joaquin killed or captured. For about two months the rangers did little but chase rumors. Then one day they came on a group of Mexicans sitting around a campfire. After the rangers had asked a few questions, both groups began shooting. The rangers killed two of the band and captured two. One of the dead was identified as Manuel Garcia, a notorious thief and murderer better known as Three-Fingered Jack; the other, though not identified, was said to have referred to himself as the leader. Since the reward offered had been only for a Joaquin, the rangers quickly decided that the dead leader was a Joaquin. They cut off his head and the hand of Three-Finger Jack. These mementos were taken to Sacramento. A grateful legislature added $5,000 to the government’s reward and the grisly relics, preserved in jars of alcohol, were exhibited in various California towns. It should be noted that the first reports said only that this head belonged to Joaquin. No last name was mentioned. Later, however, the rangers obtained affidavits that the head belonged to Joaquin Murieta, a man wanted for murder. Three Mexicans in the party who had escaped said later that the beloved man was Joaquin Valenzuela. The Alta California, a San Francisco newspaper, denounced the ranger action as a humbug. The Joaquin fiasco might have been forgotten except for the appearance in 1854 of a fictional paperback entitled the Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta, the Celebrated California Bandit by John Rollin Ridge. The lurid word made Murieta a legendary Robin Hood who suited the romantic tastes of the readers of his time. The work was pirated by many other hack writers until the fictitious and heroic Joaquin Murieta became, in many people’s minds, a historic character-so historic that two of California’s best early-day historians, H.H. Bancroft and Theodore Hittell, put him in their serious texts as a real person.

Destined to Divorce an Excerpt from Object Matrimony

Deacon Joe Sleet’s correspondence with widow Nellie Wallace was full of promise for the future. When they began writing one another in late 1925, Mrs. Wallace had hoped to find a man who would love and care for her as her deceased husband once had. When she placed an ad in the “Get Acquainted” section of a western magazine and the deacon responded she believed he was the answer to her heart’s longing. “I’m not a flapper,” her advertisement read, “but I would like to exchange letters with a man between the age of twenty-five and thirty-two. I want a husband good and true, there is a chance it might be you,” the notice concluded.

Twenty-two year old Nellie Wallace lived in Tchula, Mississippi 1,500 miles from Joe Sleet’s home in El Paso, Texas. Of all the letters she received in reply to her ad, Joe struck her fancy completely. In a short time Nellie was writing Joe to the exclusion of anyone else. Through his letters she learned that he was a deacon in the Baptist church and that he was a widower. Nellie confided in him that she too was the victim of a sad romance, her husband having died some years ago.

The correspondence was hardly a month old before Joe had been granted permission to call his fair correspondent “Sweetheart.” Another week and respective photographs were exchanged; still another and a row of x’s appeared at the bottom of their letters. Another month passed and more letters were delivered at the Sleet home. In one of those letters Nellie admitted there was a “spark of love aglow,” in her heart.

The fervor of the letters increased with their frequency. Then came the inevitable exchange of locks of hair with Nellie giving an accurate description of herself. She informed Joe she was five feet, eight inches tall, weighed 180 pounds but, being tall, did not look obese. “And goodness knows,” the account concluded, “I like to eat.” Her devotion to the truth did not quench the flame of Joe’s growing love for Nellie. “Sweetheart,” he replied, “your age, weight, hair, eyes and everything is all right with me if you will only make some suggestion about the ‘yes’ part of it. Say ‘yes’ now, Nellie. Your loving Joe.”

Nellie’s letter back to Joe included the answer he had pleaded for and he was elated when he sent a note back to her telling of his joy. In this ecstatic note Joe drew a picture of his heart with “love drops” falling from it. “Now you can see,” was the accompanying comment, “that my heart belongs to you.” He signed his letter “Your All-the-Time Valentine.”

At a later date Joe sent another letter detailing what train Nellie needed to take to get to him and what was to happen once she arrived in Texas. “We will be married at my home the night you arrive. I live with my mother. I am keeping our plans a secret from the pastor. I will tell him on Sunday that I am going to call a deacon’s meeting at my home on Thursday night and that the three deacons and I want him to be present. He will think it is just a regular business meeting until he finds out that one of his deacons wants him to officiate the happiest occasion of his life.”

It was that rosy promise and the anticipation of a joyous future that Nellie caught the next train for El Paso. The ceremony came off on schedule and Nellie, happy to escape bachelor-girlhood, joyous in her new found love, thought that her life couldn’t get any happier. Her happiness was short-lived however.

The first real problem between Nellie and Joe started with Joe’s mother. She did not like Nellie and was not shy about showing it. The two women could not agree on anything and were vocal about it. Furthermore, the groom had been led to believe, because of Nellie’s acknowledged fondness of food, that she would be able to make lavish meals. Joe was doomed to disappointment. Within a month the disgruntled bridge groom, fed up with the bickering and lack of home cooked meals by his wife, quietly disappeared one day. Joe’s mother broke the news to her daughter-in-law that her new spouse had moved to Chicago. Nellie was humiliated and furious. She moved to a neighbor’s house and began making plans to divorce Joe. In the meantime she found a job as a caretaker for an elderly woman. Joe beat Nellie in filing for a divorce citing as his reasons that his “mail-order bride,” had refused to cook his meals, fought with his mother, threatened his mother’s life and demanded that his mother leave. Nellie quickly countersued on the grounds of desertion. According to the October 5, 1926 edition of the El Paso Times, Nellie was, mortified by Joe’s accusation. “I don’t want him anymore,” she told a Times reporter. “And I wouldn’t live with him, but I am determined to go to court and to show him up.”

Meanwhile, the deacon sadly thought over his broken dreams and put himself on record with the Times as being “through” with mail-order matrimony. “I found out a month after the wedding,” he affirmed, “that our marriage was a mistake.” “I tried to get my wife to go back to her own mother. She refused. She wanted us to get a house to ourselves. I could not afford to do that. There was no use trying to reason with her. I left El Paso for Alexandria, Louisiana, my old home, where I remained a week. I did not leave her, as she claims, penniless. There was a deposit of $75 in the State National Bank, which was available for a ticket to Tchula, Mississippi.”

The divorce case took time to prepare. Meanwhile, the congregation of the church where Joe served was divided in their feelings and greatly concerned over the matter. There were those that sided with the bride and those who declared themselves to be loyal supporters of the deacon.

During a Sunday morning service directly following the announcement of the official breakup of the newlyweds, the atmosphere was electric with unvoiced opinion. The bride and groom sat on opposite sides of the church and members of the congregation who had taken a side in the matter sat with the person they believed had the most legitimate case.

When the case finally came to trial thousands of El Paso residence flooded the courtroom to hear the outcome of the troubled marriage between the deacon and his mail-order bride. The Sleet’s divorce was finalized on October 1, 1926.

Nellie and Joe Sleet’s mail-order marriage wasn’t the only correspondence romance that ended in bitter divorce. In 1914, Leola McGover from Excelsior Springs, Missouri waited patiently to walk down the aisle of the Methodist church in Silver City, Idaho and exchange vows with Lawrence Woodring, a miner who was living in Silver City. The couple had met via an advertisement Lawrence posted in the New Plan magazine. He was searching for a wife and Leola answered the call. They corresponded for more than two years before Lawrence proposed. The date of June 14, 1914 was set the wedding. The interesting outcome of the much anticipated event made the Town Talk section of the Coeur d’Alene Press. According to the articled dated June 22, the wedding between Leola and Lawrence was to be an “elegant event.” Among the bridesmaids was a cousin from Kansas City, Missouri. The groom and the cousin got along very well and the bride-to-be was pleased. Leola wanted her husband to like all the members of her family.

On the day of the wedding the church was packed with relatives and friends of both families. “The intended bride was beautiful in her marriage garb,” the Town Talk article read. “She was as happy as any girl has a right to be. Suddenly the blow fell. It was a horrible blow. It came from a note – a note from the man who was to have been her husband within the hour.”

“Leola,” the note began. “I’m sorry, but there’s nothing else that I can do. Your cousin and I fell madly in love the moment we looked at each other. Our happiness lies together. And if I married you I would put a curse on both our lives. Please do your best to forgive me.”

Leola was stunned by the revelation and fainted. Lawrence and his former fiancé’s cousin traveled to Kansas City, Missouri where they were married shortly thereafter. Leola left Idaho and settled in San Francisco.

The five brides of George Stevens experienced similar shock and dismay when they learned the man they wed was married to several others. From 1929 to 1932, sixty-three year old Stevens used the matrimonial agency the American Friendship Society to find a suitable partner to marry. Stevens was a traveling shoe salesman for the Stride Rite Shoe Company based out of Cincinnati, Ohio.

According to the May 21, 1932 edition of the Hutchinson, Kansas newspaper the Hutchinson News, Stevens told representatives at the five different American Friendship Society offices across the state that “he was lonely and needed a faithful wife.” The Society was successful in being able to match Stevens with just such women. After exchanging a few letters with Blanche Burch of Athens, Ohio, Lulu Burke of Plainwell, Cora Hamilton of Union City, Utha Liggett of Margurette Springs, and Mary Endres of Oberlin, he arranged to meet them. Not long after their initial meetings he proposed and quickly married. After each wedding he spent about a month with his brides then departed with whatever cash or jewelry of theirs he could make off with.

Lulu Burke was the first to report Stevens to Athens’ police. He deserted her in October 1931 taking $11 in cash and her checkbook with him when he left. It wasn’t until Utha Liggett came forward to report that her husband stole $800 from her that the authorities noticed a similarity in the crimes and the description of Stevens. By reviewing teletypes exchanged between police forces statewide law enforcement was able to identify the accused as the same man. Further investigation showed that Stevens was not only married to Burke and Liggett but three other women besides.

Steven was arrested at a hotel room in Cincinnati, Ohio on May 2, 1932 and charged with bigamy and theft.

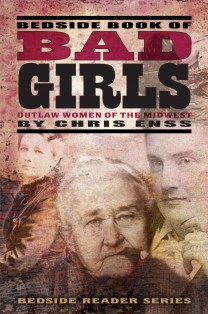

He Had It Comin’

Okay, it’s not a tale about an Old West figure, but it is one that seems to fit the season in a way. A child was born to suffer and die for our sins. Pontius Pilate, the Bible tells us, played one of the crucial roles in the history of religion-he ordered the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. But the Bible never says what became of him afterward. Pilate, as procurator of Judea, ruled the region on behalf of the Roman Emperor Tiberius for ten years, from A.D. 26 to 36. He was considered a harsh ruler and incited trouble among his Jewish subjects from the start. After he installed symbols of the Emperor the Jews complained to Rome that the emblems represented false idols and got Pilate to remove them. He turned around and issued coins with pagan symbols, and caused riots when he took money from the Jewish temples to build and aqueduct. By the time the Jewish priests pressured him to execute Christ, some say, Pilate obliged them in order to avoid further confrontation. If so, his acquiescence didn’t last long. In A.D. 36 Pilate finally was recalled by Rome to answer charges of cruelty and oppression after he massacred a group of Samaritans. Pilate arrived in Rome to find the Emperor Tiberius dead and Caligula in his place. Soon after, according to the fourth-century writer Eusebius, Pilate committed suicide. It is unclear whether Caligula ordered Pilate to kill himself or whether Pilate did it in anticipation of the vicious Emperor’s sentence. There is a legend that Pilate’s body was thrown into the Rhone River, where he caused the same trouble. His body finally was put to rest, it is said, in a deep pool in the Alps. Among some early Christians, Pilate’s suicide was seen as repentance for his execution of Christ. In other news, be one of the first five people to request a copy of the Bedside Book of Bad Girls: Outlaw Women of the Midwest and the book shall be yours. For those you know who like true tales of western baddies this will make the perfect gift.

Okay, it’s not a tale about an Old West figure, but it is one that seems to fit the season in a way. A child was born to suffer and die for our sins. Pontius Pilate, the Bible tells us, played one of the crucial roles in the history of religion-he ordered the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. But the Bible never says what became of him afterward. Pilate, as procurator of Judea, ruled the region on behalf of the Roman Emperor Tiberius for ten years, from A.D. 26 to 36. He was considered a harsh ruler and incited trouble among his Jewish subjects from the start. After he installed symbols of the Emperor the Jews complained to Rome that the emblems represented false idols and got Pilate to remove them. He turned around and issued coins with pagan symbols, and caused riots when he took money from the Jewish temples to build and aqueduct. By the time the Jewish priests pressured him to execute Christ, some say, Pilate obliged them in order to avoid further confrontation. If so, his acquiescence didn’t last long. In A.D. 36 Pilate finally was recalled by Rome to answer charges of cruelty and oppression after he massacred a group of Samaritans. Pilate arrived in Rome to find the Emperor Tiberius dead and Caligula in his place. Soon after, according to the fourth-century writer Eusebius, Pilate committed suicide. It is unclear whether Caligula ordered Pilate to kill himself or whether Pilate did it in anticipation of the vicious Emperor’s sentence. There is a legend that Pilate’s body was thrown into the Rhone River, where he caused the same trouble. His body finally was put to rest, it is said, in a deep pool in the Alps. Among some early Christians, Pilate’s suicide was seen as repentance for his execution of Christ. In other news, be one of the first five people to request a copy of the Bedside Book of Bad Girls: Outlaw Women of the Midwest and the book shall be yours. For those you know who like true tales of western baddies this will make the perfect gift.

Judge Bean

Of all the justices of the peace in the frontier west, the most publicized was Roy Bean, who held court in a rickety saloon in the arid chaparral country of southwestern Texas. Bean, of Kentucky birth, had been a trader in Mexico until settling at San Antonio. In the early 1800’s the Southern Pacific began building westward from the town, and Merchant Bean followed the construction camps to sell food, cigars, and liquor to the workers. Bean had little book learning, but his beard and his dignified appearance led some to bring their disputes to him for decision. Before long, with the nearest court nearly two hundred miles away, even the Texas Rangers began bringing prisoners to him for judgment. Late in 1882 the Rangers obtained his appointment as a justice of the peace. When the rail line was completed, Roy Bean settled at a dusty village named Langtry, near the Rio Grande and at the eastern edge of the mountainous Big Bend area. In 1884 his status as justice of the peace was continued by election. He obtained a blank book in which he wrote he “statoots,” along with his poker rules. With no jail at hand, Bean kept prisoners chained to a nearby mesquite tree and let them sleep in the open, with gunnysacks for pillows. Trials regularly opened and closed with drinks at his bar, and any long session probably would be interrupted with recesses for quenching thirst. Once an Irishman was brought before him on a charge of having killed a Chinese railroad worker and some of the defendant’s husky friends came along and made it plain to Bean that a wrong decision would lead to the boycotting or wrecking of his bar. Faced with this threat, the justice gravely thumbed through his law book and announced that he found no statute against the killing of a Chinaman. The drinks, he quickly added, would be on the Irishman. Bean lived comfortably from his sale of beer and from his fines, which he pocketed. Even a dead man was not immune from being fined. When the body of Pat O’Brien, killed by falling from a high bridge, was brought before Bean, the judge found that the dead man had a six-shooter and forty dollars. Quickly he confiscated the gun and fined the dead man forty dollars for carrying a concealed weapon.

Hearing From God

Of all the women I’ve written about that have left their mark on politics or politicians, Joan of Arc is the most admirable. She made political and royal figures nervous and questioning their beliefs. The fifteenth century woman became a much talked about figure when she made public that she was hearing voices. To her, God had a message of insider military information, instructing her to drive the English out of France. She dressed for battle and showed up for war, and by her conviction (others called it madness) she rallied the troops and achieved a long sought victory of a key occupied city in just nine days. French King Charles VII, his own lineage rife with frequent bouts of insanity, dubbed her and her family nobility. A year later she was captured by the English, tried for heresy by the clergy of the Inquisition, and burned at the stake at age nineteen in 1431. Charles VII made no effort to free her. Five hundred years later she was canonized as a saint. Between 1450 and 1600, records indicate at least 30,000 were burned or executed as heretics or witches. The torture devises used during this period go beyond what the cruelest of masochistic minds could imagine, including water torture, racks, fingernail pullers, skull-and-limb crushing vices, burning feet machines, and metal chambers shaped like statues of the Virgin Mary lined with spikes in which the accused was enclosed to elicit a confession of heresy. The instruments were blessed prior to use; however in 2002, Pope John Paul II issued a general apology for this and for the “errors of his church for the last 2000 years.”