Recognizing heroic women in history continues today with a look at two ladies that were born centuries apart who made an impact. A fifteenth-century French woman known as Joan of Arc began to hear voices. To her, God had a message of insider military information, instructing her to drive the English out of France. She dressed for battle and showed up for war, and by her convictions (others called it madness) she rallied the troops and achieved a long-sought victory of a key occupied city in just nine days. French King Charles VII, his own lineage rife with frequent bouts of insanity, dubbed her and her family nobility. A year later she was captured by the English, tried for heresy by the clergy of the Inquisition, and burned at the stake at age nineteen in 1431. Charles VII made no effort to free her. Five hundred years later she was canonized as a saint. Few women choose their hero path via exploration. One notable exception was May French-Sheldon, a wealthy American woman who became known as the first woman explorer of Africa. In the 1890s, with an entourage of 130 Zanzibarian men, she explored East Africa and the Congo. The press at the time called her a raging madwoman, but she didn’t care. She went on to lecture for many years about her travels, stressing-way before it was fashionable-that a “woman could do anything a man could.” She died of pneumonia in 1936 at age eighty-nine.

Recognizing heroic women in history continues today with a look at two ladies that were born centuries apart who made an impact. A fifteenth-century French woman known as Joan of Arc began to hear voices. To her, God had a message of insider military information, instructing her to drive the English out of France. She dressed for battle and showed up for war, and by her convictions (others called it madness) she rallied the troops and achieved a long-sought victory of a key occupied city in just nine days. French King Charles VII, his own lineage rife with frequent bouts of insanity, dubbed her and her family nobility. A year later she was captured by the English, tried for heresy by the clergy of the Inquisition, and burned at the stake at age nineteen in 1431. Charles VII made no effort to free her. Five hundred years later she was canonized as a saint. Few women choose their hero path via exploration. One notable exception was May French-Sheldon, a wealthy American woman who became known as the first woman explorer of Africa. In the 1890s, with an entourage of 130 Zanzibarian men, she explored East Africa and the Congo. The press at the time called her a raging madwoman, but she didn’t care. She went on to lecture for many years about her travels, stressing-way before it was fashionable-that a “woman could do anything a man could.” She died of pneumonia in 1936 at age eighty-nine.

Journal Notes

Missing Pioneer

Amelia Earhart was the first female aviation hero. She was a likable, slender woman with an independent mind. Determined to do anything a man could do, despite the obstacle, she drove a truck and worked at the telephone company to earn the money needed for her first flying lessons. She had the right image and was photogenic enough to be asked to make a sponsored, first female-copiloted flight across the Atlantic. Publisher George Putnam was going to do a book on this and met the young woman to determine her candidacy. Apparently, she was more than photogenic because this meeting ultimately led to their “open marriage” and a relationship that Earhart agreed to only if the “medieval code” of fidelity by either part was not followed. At the age of thirty-nine in 1937 she attempted to circumnavigate the globe. Similar to Magellan’s fate, she got only three-quarters of the way when her plane ran out of fuel and crashed into the Pacific Ocean. What really happened to her is unknown, with theories ranging from being captured by the Japanese and treated as a spy, to her living a life of solitude on a deserted island with a native fisherman. However, it is most probable that no sign of her body was ever recovered because she was eaten by sharks.

Amelia Earhart was the first female aviation hero. She was a likable, slender woman with an independent mind. Determined to do anything a man could do, despite the obstacle, she drove a truck and worked at the telephone company to earn the money needed for her first flying lessons. She had the right image and was photogenic enough to be asked to make a sponsored, first female-copiloted flight across the Atlantic. Publisher George Putnam was going to do a book on this and met the young woman to determine her candidacy. Apparently, she was more than photogenic because this meeting ultimately led to their “open marriage” and a relationship that Earhart agreed to only if the “medieval code” of fidelity by either part was not followed. At the age of thirty-nine in 1937 she attempted to circumnavigate the globe. Similar to Magellan’s fate, she got only three-quarters of the way when her plane ran out of fuel and crashed into the Pacific Ocean. What really happened to her is unknown, with theories ranging from being captured by the Japanese and treated as a spy, to her living a life of solitude on a deserted island with a native fisherman. However, it is most probable that no sign of her body was ever recovered because she was eaten by sharks.

The Death of Jeanne Eagels

In 1929 Jeanne Eagels was nominated for a best actress Oscar for The Letter after she died earlier that year at age thirty-nine from alcohol and heroin complications. Eagles had started as a Ziegfeld Follies girl, but her talent and beauty soon moved her from the chorus line to center stage. Tabloids of the time followed her progress and her secret marriage to a Yale football star, and they especially liked her temper, her no-shows, and her quitting plays whenever she felt like it. At one point she was banned from appearing on stage by Actors Equity, which had forced her to move to Hollywood to make the “talkie” The Letter, one of the first films that showed the true dramatic possibilities of audio in cinema. In the fall of 1929 she checked into a private drying-out hospital in New York City a week before the stock market crashed; unfortunately she left via the morgue. During the 1920s heroin was used with impunity on Broadway, and many actors made their daily runs to the thriving heroin shops operating in New York’s Chinatown before and after every performance. By 1929 there was 200,000 heroin addicts in the United States. The prevailing treatment at the time consisted of treating the drug addict with more drugs, particularly more potent morphine derivations, which often caused fatal overdoses. Many Old West actors performed under the influence particularly at the Tabor Opera House in Colorado.

In 1929 Jeanne Eagels was nominated for a best actress Oscar for The Letter after she died earlier that year at age thirty-nine from alcohol and heroin complications. Eagles had started as a Ziegfeld Follies girl, but her talent and beauty soon moved her from the chorus line to center stage. Tabloids of the time followed her progress and her secret marriage to a Yale football star, and they especially liked her temper, her no-shows, and her quitting plays whenever she felt like it. At one point she was banned from appearing on stage by Actors Equity, which had forced her to move to Hollywood to make the “talkie” The Letter, one of the first films that showed the true dramatic possibilities of audio in cinema. In the fall of 1929 she checked into a private drying-out hospital in New York City a week before the stock market crashed; unfortunately she left via the morgue. During the 1920s heroin was used with impunity on Broadway, and many actors made their daily runs to the thriving heroin shops operating in New York’s Chinatown before and after every performance. By 1929 there was 200,000 heroin addicts in the United States. The prevailing treatment at the time consisted of treating the drug addict with more drugs, particularly more potent morphine derivations, which often caused fatal overdoses. Many Old West actors performed under the influence particularly at the Tabor Opera House in Colorado.

Wedding Gowns and Scientists

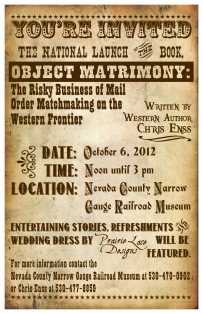

Before I write about another extraordinary woman from history I’d like to congratulate Barbara Bognanno-Badger for winning the wedding dress given away at the launch of the book Object: Matrimony. Barbara’s name was selected at random from more than two hundred ten entries. The gown is from Prairie Lace Designs and is valued as $5,000. Enjoy the gown, Barbara. And now, from bridal wear winners to physics. The first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize was Marie Curie in 1903 for Physics. She became the only woman to receive two Nobel Prizes, when she was awarded the prize for Chemistry in 1911. Her work with radiation and the discovery of the elements radium and polonium opened the doors for many advances in science and medicine. Soon after Madame Curie won the 1911 prize, she was hospitalized for depression and kidney problems and suffered from ill health the remainder of her life. The dangers of radiation were not understood and she often worked unprotected with radioactive substances. She died in 1934 at age sixty-six of aplastic anemia, a bone marrow condition caused by radiation. In 1938 Marie’s daughter, Irene Joliot Curie, won a Nobel Prize for Chemistry for her work with neutrons, setting the stage for nuclear fission. She died of leukemia at age fifty-eight in 1956 as a result of being exposed to radiation while assisting her mother years before.

The Empress of Blues

Bessie Smith began her professional singing career at the age of eighteen in 1912, earning eight dollars a week. For many years she toured on the minstrel and vaudeville show circuit until she made her first recording in 1923. “Down Hearted Blues,” which sold over 750,000 copies in the first year, thereby making her the most successful black performer of her era. Her stage performances then earned fifteen hundred dollars per session, a tremendous sum at the time, although she received no royalties from the recordings; Bessie Smith received only thirty dollars per record of the one hundred sixty she recorded. Although many would now consider that she was duped into signing such a recording contract, Bessie was a hard-drinking, swaggering woman who reportedly would get into a knockdown fight over the slightest insult. The woman known as Empress of the Blues lived hard and fast. She died at the age of forty-three in 1937, in Mississippi. The speeding car she drove in as a passenger slammed into the rear end of a truck. Her arm was nearly severed, and she died of trauma and blood loss. Her bootlegger boyfriend, Richard Morgan, the driver of the car, was unharmed. No Breathalyzer tests were available to determine the root cause of the accident. Newspaper reports suggested that Bessie Smith died because she was taken to a segregated white hospital that refused treatment. However, records confirm that she was transported directly to Clarksdale’s, a black hospital, where she died six hours later.

The Celebrated Spoiled One

Pocahontas, a nickname meaning “little spoiled one,” was born Amonute, daughter of Chief Powhatan in 1595. She was an extrovert from a young age, inquisitive and naturally good-natured. At eleven years old she played a minor role in securing John Smith’s survival. Later she was the go-between for trade among the settlers and Indians bartering at Jamestown. The fictionalized version of her love affair with Smith may, in fact, bear some truth, but in a much more disturbing way for our modern sensibility. Today, a thirty-year-old having sex with a preteen in pedophilia and a crime. But, in that era, intercourse with non-Christian pagans of any age was not considered wrong. Pocahontas was known to have “long, private conversations” with Smith during her frequent visits to the Jamestown complex, yet the true dimensions of these encounters are a matter of conjecture. A few years later she was betrothed to the older Englishman John Rolfe, only after she agreed to be baptized in 1614. Two years later Rolfe took her to London, where she was received as a celebrity, billed as a real live Indian princess by high society, and held an audience with King James. In 1617 she believed the smoky air of London was the cause of her coughs and bouts of weakness and wished to return to the forests she had known. Along with Rolfe she boarded a ship to return to Virginia, but the vessel only made it to the end of the Thames River before it turned back. Pocahontas died in London at age twenty-two of disease called the king’s evil, a form of tuberculosis characterized by swelling of the lymph glands.

Being First

A Pioneer with Vision

Helen Keller was a pioneer for rights of the disabled. In 1891 when she was nineteen months old, she fell ill from scarlet fever, which left her not only blind but deaf as well. At seven years old she was taken to Alexander Graham Bell, an expert on hearing and speech, who encouraged her parents to enroll Helen in the Institute for the Blind in Boston. There, in her frustration to communicate, she would seem wild, thrashing about and was at first considered to have no mind capable of understanding – in short, an imbecile. Helen’s father found a live-in private tutor, twenty-year old Anne Sullivan, who taught Helen how to finger-spell, as Braille was then called. She learned the code for W-A-T-E-R, but never knowing light or sounds, Helen couldn’t correlate the words to the liquid these letters spelled. Anne thrust Helen’s hand under water flowing from a pump, followed by the letters for water tapped into her hand. Suddenly Helen realized that the cool substance coming from the pump had a name and quickly learned how to read, write, and eventually speak. With Anne Sullivan’s continued friendship, Helen became the first blind and deaf person to graduate from college in 1901. In 1915 the two women founded Helen Keller International, a nonprofit organization that worked to prevent blindness. Not only did Helen become an international speaker, writing twelve books, she also starred in a silent movie and tried her hand at a vaudeville tour. She died of Ondine syndrome during a nap in 1968 at the age of eighty-seven. Anne Sullivan also had a visual impairment, caused when doctors rubbed cocaine on her eyes before performing a procedure to treat pink eye when she was a child. By 1935, a year before her death, she was totally blind. She died at age seventy of coronary artery disease.

Women of Invention

The first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize was Marie Curie in 1903 for Physics. She became the only woman to receive two Nobel Prizes, when she was awarded the prize for Chemistry in 1911. Her work with radiation and the discovery of the elements radium and the polonium opened the doors for many advances in science and medicine. Soon after Madame Curie won the 1911 prize, she was hospitalized for depression and kidney problems and suffered from ill health the remainder of her life. The dangers of radiation were not understood and she often worked unprotected with radioactive substances. She died in 1934 at age sixty-six of aplastic anemia, a bone marrow condition caused by radiation. In 1938 Marie’s daughter, Irene Joliot-Curie, won a Nobel Prize for Chemistry for her work with neutrons, setting the stage for nuclear fission. She died of leukemia at age fifty-eight in 1956 as a result of being exposed to radiation while assisting her mother years before. Tomorrow is the big launch for the book Object: Matrimony. Everyone is invited to attend the festivities held at the Railroad Museum in Nevada City from noon to 3 p.m.. Register to win a beautiful wedding gown by fashion designer Christian Michael Goodwin. The gown was inspired by the dresses the mail-order brides of the Old West wore, but has a contemporary flair.

The first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize was Marie Curie in 1903 for Physics. She became the only woman to receive two Nobel Prizes, when she was awarded the prize for Chemistry in 1911. Her work with radiation and the discovery of the elements radium and the polonium opened the doors for many advances in science and medicine. Soon after Madame Curie won the 1911 prize, she was hospitalized for depression and kidney problems and suffered from ill health the remainder of her life. The dangers of radiation were not understood and she often worked unprotected with radioactive substances. She died in 1934 at age sixty-six of aplastic anemia, a bone marrow condition caused by radiation. In 1938 Marie’s daughter, Irene Joliot-Curie, won a Nobel Prize for Chemistry for her work with neutrons, setting the stage for nuclear fission. She died of leukemia at age fifty-eight in 1956 as a result of being exposed to radiation while assisting her mother years before. Tomorrow is the big launch for the book Object: Matrimony. Everyone is invited to attend the festivities held at the Railroad Museum in Nevada City from noon to 3 p.m.. Register to win a beautiful wedding gown by fashion designer Christian Michael Goodwin. The gown was inspired by the dresses the mail-order brides of the Old West wore, but has a contemporary flair.

Freedom Fighter

Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823-1893) was an educator and abolitionist. She was the first black woman to graduate from Howard University Law School and the first black woman to vote in a federal election. She helped President Lincoln enlist black men to fight in the Union and her house was frequently a safe haven in the Underground Railroad for slaves fleeing the South. After the war she became a school principal, and then a lawyer in Washington, D.C., at the age of sixty. She died in 1893 at age seventy from heart failure, with an estate valued at $150.

Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823-1893) was an educator and abolitionist. She was the first black woman to graduate from Howard University Law School and the first black woman to vote in a federal election. She helped President Lincoln enlist black men to fight in the Union and her house was frequently a safe haven in the Underground Railroad for slaves fleeing the South. After the war she became a school principal, and then a lawyer in Washington, D.C., at the age of sixty. She died in 1893 at age seventy from heart failure, with an estate valued at $150.