Journal Notes

Making My Way Home

While sitting at the airport enduring the late flights and pajama wearing, no showering, multiple carry-on passengers, I decided to try and catch up on the daily journal section of my site. It’s been long but enjoyable two week adventure releasing of the book Sam Sixkiller: Cherokee Frontiers Lawman to the public. I began the journey in Colcord, Oklahoma where United State marshal Sam Sixkiller rode collecting bootleggers and murderers and I ended the trip in the hills around Edgewood, New Mexico where Billy the Kid spent time with his riders. In between I got to meet great western authors like Johnny Boggs and Sherry Monahan and hang out with actor Wes Studi. It will be good to get home and return to work, however. Getting updates on the Broadway production and the motion picture will be focus this week. But first, just to be home. As Charles Dickens once wrote, “Home is a name, a word, it is a strong one; stronger than magician ever spoke, or spirit ever answered, in the strongest conjuration.” That and I’m out of clean underwear.

Count It All Joy

Chuck Swindoll tells a story about a young man named Glen Chambers. Glen had a heart to serve God on the mission field. He got his training, went to Bible college, went to seminary, and he raised his support. He left everything behind and boarded a plane to fly as a missionary to South America. He had gone through the strain of financial problems and misunderstanding with family. He’d dealt with the pain of separation, and he was filled with hope and anticipation and excitement about serving Christ. As he was about to fly, he thought to himself, I really should have said more to my parents, so he tore off a corner of a magazine and wrote them a little note: “Mom and Dad, I’m so excited, going to serve Christ. Thanks for getting behind me in this. I love you, Glen.” Glen stuffed the note in an envelope and put it in the mail to his parents. Glen got on the plane, and in the middle of the night, a mountain in the jungles of Ecuador reached up, pulled that plane out of the sky, and Glen was killed in a plane crash. He never made it. All the training, all the fundraising-everything-and he never got there. After the funeral was over, his parents got the letter Glen wrote. They opened it. It turns out that on the back of the magazine corner he’d torn off to write that note was printed one word: “why.” Why? That’s the question that hits the hardest, isn’t it? It’s the question that hurts the most…lingers the longest…and it’s the question that every follower of Jesus Christ has asked. I’ve asked it so many times. Why, God? And it’s the question James helps us answer. James 1:2-4 Consider it pure joy, my brothers, whenever you face trials of many kinds because you know that the testing of your faith develops perseverance. Perseverance must finish its work so that you may be mature and complete, not lacking anything. In this world there will be pain and suffering. There’s just no getting around it. It a sure thing. Surer still is that God has overcome this world. God has a reason…a good reason. The nail that doesn’t remain under the hammer will never reach the goal. The diamond that doesn’t remain under the chisel will never become a precious jewel. The gold that doesn’t remain under the fire will never be refined.

Juanita Put to Death

The Fourth of July celebration held in Downieville, California, in 1851 was a festive event that included a parade, a picnic, and patriotic speeches from numerous politicians. Proud members of the Democratic County Convention spoke to the cheering crows of more than five thousand people, primarily gold miners, about freedom and the idea that all are considered equal. The celebration was accentuated with gambling at all the local saloons and the consumption of alcohol, available in large barrels lining the streets. When residents weren’t listening to orators wax nostalgic, many happy and drunk souls gathered at Jack Craycroft’s Saloon to watch a dark-eyed beauty named Juanita deal cards. Juanita was from Sonora, Mexico, and engaged to the saloon’s bartender, but that did not stop amorous miners from attempting to get close to her. Fred Cannon, a well-liked Scotsman who lived in town, frequently propositioned Juanita. On the Fourth of July in 1851, he took her usual rejection particularly hard and threatened to have his way with her regardless. When Juanita finished work that evening, she went straight home. The streets were still busy with rowdy patriots who weren’t willing to stop celebrating. Fred Cannon was among the men on the thoroughfare who were drinking and firing their guns in the air. After more than a few beers, Fred decided to take the celebration to Juanita’s house. Juanita was preparing for bed when Fred pounded on the front of her home and suddenly burst in, knocking the door off the hinges. She yelled at the drunken man to get out. Before leaving, Fred cursed at her and threw some of her things on the floor. The following morning Juanita confronted Fred about his behavior and demanded he fix her door. He refused, insisting that the door was flimsy and was in danger of falling off the frame prior to his involvement. Juanita was enraged by his response, and the two argued bitterly. When Fred cursed at her this time, she pulled a knife on him and stabbed him in the chest. Fred’s friends surrounded the woman, calling her a harlot and a murderer. They demanded that she be hanged outright. Many of the townspeople insisted on trying her first, however. After a quick and biased hearing, Juanita was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged. The fearless woman held her head up as she was led to the spot where she would be put to death. She refused a blindfold, and when asked if she had any final words about the crime for which she was accused, she simply nodded her head. She boldly stated that she was not sorry and that she would “do it again if so provoked.” Juanita was the first woman to be hanged in the state of California. She was buried in the same grave as Fred Cannon. The pair was moved from the site six months later when gold was discovered where they laid. Their remains were relocated to the Downieville Cemetery. Time and the elements have erased the name of the infamous Juanita from the marker that stands over her grave.

The Murder of Julia Bulette

Red, white and blue bunting hung from the windows and awnings lining the main street of Virginia City, Nevada on July 4, 1861. The entire mining community had turned out to celebrate the country’s independence and share in the holiday festivities. The firemen of Fire Engine Company Number 1 led a grand parade through town. Riding on top of the vehicle and adorned in a fireman’s hat and carrying a brass fire trumpet filled with roses was Julia Bulette. The crowd cheered for the woman who had been named Queen of the Independence Day parade, and Julia proudly waved to them as she passed by. In that moment residents looked past the fact that she was a known prostitute who operated a busy parlor house. For that moment they focused solely on the charitable works she had done for the community and, in particular, the monetary contributions she had made to the fire department. Julia Bulette had been born in London, England, in 1833. She and her family moved to New Orleans in 1848 and then on to California with the gold rush. Julia arrived in Virginia City in 1859 after having survived a failed marriage and working as a prostitute in Louisiana. In a western territory where the male inhabitants far outnumbered the female, doe-eyed Julia learned how to make that work to her advantage. She opened a house of ill repute and hired a handful of girls to work for her. Julia’s Palace, as it came to be known, was a high-class establishment complete with lace curtains, imported carpets, and velvet, high-back chairs. She served her guests the finest wines and French cooking and insisted that her gentlemen callers conduct themselves in a civilized fashion. She was noted for being a kind woman with a generous heart who never failed to help the sick and poor. In recognition of her support to the needy, the local firefighters made her an honorary member. It was a tribute she cherished and did her best to prove herself worthy. On January 21, 1867, Virginia City’s beloved Julia was found brutally murdered in the bedroom of her home. The jewelry and furs she owned had been stolen. The heinous crime shocked the town, and citizens vowed to track the killer down. The funeral provided for Julia was one of the largest ever held in the area. Businesses closed, and black wreaths were hung on the doors of the saloons. Members of Fire Engine Company Number 1 pooled their money and purchased a silver-handled casket for her burial. She was laid to rest at the Flowery Cemetery outside Virginia City. The large wooden marker over her grave read simply JULIA. Fifteen months after Julia’s death, law enforcement apprehended the man who robbed and killed her. Jean Millian had been one of her clients and had Julia’s belongings on him when he was apprehended. Millian was tried, declared guilty, and hanged for the murder on April 27, 1868. This story as well as many other previous tales are from the book Tales Behind the Tombstones.

Children of the Trail

Crude rock markers and wooden crosses dot the various trails used by settlers heading west in the mid-1800s. A significant number of those markers indicate the final resting places of children. The trek across the frontier was filled with peril. Violence, disease and accidents claimed the lives of thousands of infants and toddlers. So uncertain were some pioneers of the longevity of their offspring born en route, they held off named their babies until they were two-years-old. The leading causes of death for children younger than age six traveling overland were cholera, meningitis, and smallpox. A number of children suffered fatal injuries when they fell under wagon wheels, fell into campfires, fell down steep canyons, or drowned in river crossings. In 1852, a family from Kentucky who were caught up in the gold rush barely made it out of Independence, Missouri, when their four-year-old died from meningitis. The leaders of the wagon train they were a part of stopped the caravan, and the men in the party cut down a medium-size oak tree to use as a casket for the girl. The girl’s body was laid in the shell, and the wooden slab was placed over it and nailed down. They dug a grave alongside the trail, lowered the crude casket, read a few words from the Bible, and prayed over the plot. After the grave was filled in, they flattened it by driving the wagons back and forth over the fresh earth. Pioneers believed this action kept wild animals from digging up the area. When the trip resumed the mother of the deceased child stood in the rear of the wagon, staring back at the spot where they had left her daughter. She continued staring at the spot hours after the grave was out of sight. An emigrant mother who lost her four-month-old child on the way to the fertile land of Oregon recorded a bit of the heartbreaking ordeal in her journal. In April 1852, Suzanna Townsend wrote, “we did feel very happy with her all the time she was with us and it was hard to part with her.” The journey across the rugged plains was so treacherous and risky some political leaders suggested only men should make the trip. In 1843, Horace Greeley wrote, “It is palpable homicide to tempt or send women and children over the thousand miles of precipice and volcanic sterility to Oregon.” Centuries-old cemeteries throughout the West are filled with small burial sites. More than one-third of the graves in the historic St. Patrick’s Cemetery in Grass Valley, California, represents children who have long since been gone. As in many gold-mining-camp cemeteries, marble cherubs are the most common overseers of the graves. Sculptured lambs representing innocence were also frequently used. The stories of the many lives that ended before they had a chance to make their mark on the frontier are lost forever. Only by their weathered tombstones are we able to know the tale of sacrifice to settle a new land.

Another Lawman Down

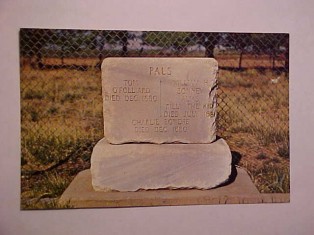

What an extreme pleasure it was to meet descendants of Cherokee lawman Sam Sixkiller this weekend in Oklahoma. Such lovely people one and all and they generously shared photographs of Captain Sixkiller’s children and grandchildren with me. I learned a great deal more about the lawman and the Nation he protected. Colcord, Oklahoma is one of the most friendly towns I ever visited and I couldn’t help but imagine Sixkiller patrolling the area. On my way home I was reminded of a lawman who made his mark on this area of California. His name was David Douglass and a short account of his life is included in the book Tales Behind the Tombstones. Douglass was elected to the post of Nevada County sheriff in 1894. Sheriff Douglass had been a guard for gold shipments traveling by train and had also served as a messenger for Wells Fargo. He was known by residents in Grass Valley and Nevada City, California, as a bold, fearless, and defiant officer, dedicated to making sure the law was upheld. On Sunday, July 26, 1896, Douglass set out after an outlaw named C. Meyers who had been terrorizing the country. The pursuit ended in the death of the bandit and the sheriff. Sheriff Douglass shot and killed the highwaymen, but just who shot Douglass remains a mystery. After learning where the thief was hiding out, Douglass, mounted his horse and took out after him. When the sheriff hadn’t returned by the next day, his friends and deputies combed the area looking for him. His body was discovered a few feet from the outlaw’s. Cedar and chaparral trees were thick around the secluded scene, and it was evident to the sheriff’s deputies that he had been lured to the spot. Sheriff Douglass’s body was found with his head pointing downhill, his face plunged in the brush and dirt. The Grass Valley Union newspaper reported that the “force of the fall brought a slight contusion to the forehead.” Those who discovered his body believed that the bullet that took his life had entered his back, thrusting him forward. The report quoted deputies as saying, “Undoubtedly Sheriff Douglass had shot Meyers dead and was going to inspect the damage when a bullet pierced his frame.” As subsequent facts developed it appeared there had been an accomplice of Meyers hiding somewhere in the area. The unknown shooter fired shots at Douglass. The first bullet went into his back on the left side, and the second hit him in the right hand. Nevada County residents were shocked by the news of the respected sheriff’s death. They arrived in droves at the scene of the tragedy hoping to find a clue as to who the murderer might have been. Dozens of well-armed men scoured the hills in search of the assassin. The killer was never found. A monument to the memory of the sheriff and the outlaw (buried at the site) was erected at the location of the tragic gunfight in early 1900. It is believed Douglass was pitted against two and then one escaped. The bodies were lying parallel to one another. The gravestone over Sheriff Douglass’s grave and that of the bandit he shot is located in the Tahoe National Forest in Nevada City, California on a dirt pathway on Old Airport Road.

The Lone Grave

It was the news of gold that let loose a flood of humanity upon the foothills of Northern California. Prior to 1849 most west-heading wagons were bound for Oregon. All at once settlers burst onto the scene searching for their fortune in gold. Some found what they hoped for, but others found nothting but tragedy. Such was the case for the Apperson family, pioneers who lost a young family member in a fiery accident in 1858. The wagon train the sojourners were a part of struggled to make its way over the treacherous Sierra Nevadas and down the other side into the valley below. The appersons and their fellow travelers were exhausted from the four-month overland trip, which had started in Independence, Missouri. After reaching the outskirts of the mining community of Nevada City, California, they made camp as usual and rested for a few days before moving the train on into town. The forest settling was idyllic, and the Appersons decided to stay there instead of going on with the others. They built a home for themselves and their four children. For a while they were truly happy. But on May 6, 1858, an unfortunate accident occurred that left them devastated. At their father’s request the Apperson children were dutifully burning household debris when the youngest boy, barely two years old, wandered too close to the flames, and his pant leg caught fire. His sister and brothers tried desperately to extinguish the flames but were unsussessful. The boy’s mother heard his frantic screams and hurried to her child. She smothered him with her dress and apron, and then quickly rushed him to a nearby waterng trough and immersed his body. The child’s legs and sides were severly burned, but he survived. For a time it seemed as though his injuries might not be life threatening. The boy lingered for a month and then died. He was buried at the southwest corner of their property. The Apperson family stayed only a few months after his death and then moved on. At the time of his passing, the grave was marked only by two small seedlings. Since then concerned neighbors and community leaders have taken an interest in the burial site, surrounding the small spot with a fence and a marker. Motorists driving along U.S. Highway 20 from Nevada City frequently stop to visit the lone grave beside the road. It lies to one side of the interstate between two large cedars. A stone plaque now stands over the place where the child lies. Donated by the Native Sons of the Golden West, the plaque reads Julius Albert Apperson, Born June 1855. Died May 6, 1858. A Pioneer Who Crossed The Plain To California Who Died And Was Buried Here. The Emigrant Trail followed along the ridge and through Nevada City. The marking of this lone grave perpetuates the memory of all the lone graves throughout the state. Not only does the plaque signify the grave as a historic landmark, it stands as a symbol of sacrifice.

Outcast Cemetery

Sam Sixkiller Now Available

Sam Sixkiller was one of the most accomplished lawmen in 1880s Oklahoma Territory. And in many ways, he was a typical law-enforcement official, minding the peace and gunslinging in the still-wild West. What set Sam Sixkiller apart was his Cherokee heritage. Sixkiller’s sworn duty was to uphold the law, but he also took it upon himself to protect the traditional way of life of the Cherokee. Sixkiller’s temper, actions, and convictions earned him more than a few enemies, and in 1886 he was assassinated in an ambush. This new biography takes a sweeping, cinematic look at the short, tragic life of Sam Sixkiller and his days policing the streets of the Wild West.