Enter now to win a copy of

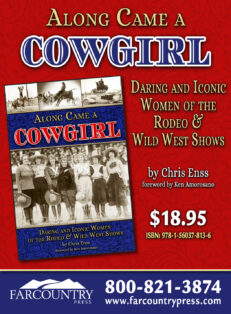

Along Came a Cowgirl:

Daring and Iconic Women of the Rodeo and Wild West Shows

Cowgirl Mamie Francis sat atop her horse, Babe, waiting for the director of California Frank Hafley’s Wild West show to let her know when the program began. Mamie and Babe were perched on a wooden platform thirty feet in the air over Coney Island, New York, looking down at the audience in the grandstands. Directly below the platform was a forty-foot tank filled to overflowing with water. It was the summer of 1908.

Mamie gently urged Babe to the edge of the platform, both stood like a beautiful statue surveying the landscape before them. After receiving the signal, Mamie coaxed Babe forward. The horse pushed away from the boards and lunged outward into space. Moments later, rider and horse entered the water in the tank with a giant splash. When they came to the surface, the audience erupted in applause. Mamie patted Babe’s neck as the horse carried her up the ramp and out the tank.

Born in Nora, Illinois, on September 8, 1885, to Charles and Anna Ghent, and given the name Elba Mae, Mamie was an accomplished equestrienne by the time she turned sixteen. Her parents moved from Illinois to Wisconsin when she was a baby. Her mother worked for a farmer who owned several horses, and it was there she learned how to ride and use a gun to hunt. When Pawnee Bill’s Wild West show stopped in Kenosha, Wisconsin, for a two-night performance, Mamie was in the audience to take in the excitement. Before the show left town, she had signed on to be one of the entertainers.

As Mamie excelled at riding and shooting, that’s what Pawnee Bill had her do in the show. In time, she would be billed the greatest horseback and rifle shot in the world. Mamie met her first husband, trick rider Herbert Skepper, shortly after joining the show. The pair was married on July 7, 1901.

By 1905, Mamie had left the Pawnee Bill’s Wild West show and divorced Skepper. Charles Francis Hafley and his wife, trick shooter Lillian Smith, were familiar with Mamie’s talents and sought her out to join Hafley’s Wild West show. She happily agreed to be a part of the troupe. During her time with the experienced group, Mamie perfected her own sharpshooting routine, tried her hand at bronc riding, and even mastered a few rope tricks.

In late 1907, she added horse diving to her repertoire. Known as the Diving Equestrienne, she and Babe made over six hundred jumps between 1907 and 1914. When Mamie stopped horse diving, she turned her attention solely to sharpshooting, trick riding, and training horses to compete in dressage* events. Mamie married Charles Hafley in November 1909, a year after he and Lillian Smith divorced. The two managed the Wild West show for thirty-one years.

Mamie Francis Hafley died on February 15, 1950. She was sixty-four years old. The National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame honored Mamie for her equestrienne skills in 1981.

*The art of riding and training a horse in a manner that develops obedience, flexibility, and balance.

To learn more about talented riders like Mamie read Along Came a Cowgirl: Daring and Iconic Women of the Rodeo and Wild West Shows. Visit www.chrisenss.com to enter to win a copy of the new book.